Farm Fires Make Pollution Worse in Delhi and Lahore

Why does the air quality in New Delhi and Lahore ranks among the world's worst at this time of the year? The answer to this oft-repeated question can be found in the satellite maps constantly updated by the US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). Indian government recently estimated that 36% of pollution was contributed by farm fires. Here's how NASA Earth Observatory explains it: "The haze visible in this image likely results from a combination of agricultural fires, urban and industrial pollution, and a regional temperature inversion. Most of the time, air higher in the atmosphere is cooler than air near the planet’s surface, and this configuration allows warm air to rise from the ground and disperse pollutants. In the wintertime, however, cold air frequently settles over northern India, trapping warmer air underneath. The temperature inversion traps pollutants along with warm air at the surface, contributing to the buildup of haze."

|

| Farm Fires Seen By NASA Satellite. Source: FIRMS |

Farm Fires:

The latest image downloaded from NASA's Fire Information for Resource Information System (FIRMS) show farm fires burning in both India and Pakistan. These fires are particularly intense in Indian and Pakistani provinces of the Punjab. These fires contribute significantly to the high level of particulates in Delhi and Lahore. Indian government recently estimated that 36% of the PM2.5 particulate matter was contributed by stubble burning by farmers.

South Asia's Vulnerability:

South Asia is particularly susceptible to pollutants that hang in the air for extended periods of time. The US National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) satellite images show dull gray haze hovering over northern India and Pakistan, and parts of Bangladesh. It is believed that emissions from solid fuel burning, industrial pollutants and farm clearing fires get trapped along the southern edge of the Himalayas. NASA Earth Observatory explains this phenomenon as follows:

"The haze visible in this image likely results from a combination of agricultural fires, urban and industrial pollution, and a regional temperature inversion. Most of the time, air higher in the atmosphere is cooler than air near the planet’s surface, and this configuration allows warm air to rise from the ground and disperse pollutants. In the wintertime, however, cold air frequently settles over northern India, trapping warmer air underneath. The temperature inversion traps pollutants along with warm air at the surface, contributing to the buildup of haze."

|

| Trapped Smog. Source: Al Jazeera |

Urgent Actions Needed:

South Asian governments need to act to deal with rapidly rising particulate pollution jointly. Some of the steps they need to take are as follows:

1. Crack down on stubble burning to clear fields. Incentivize use of machine removal of stubble.

2. Reduce the use of solid fuels such as cow dung, wood and coal to limit particulate matter released into the atmosphere.

3. Impose higher emission standards on industries and vehicles through regulations.

4. Incentivize transition to electric vehicles.

5. Increase forest cover by planting more trees.

6. Encourage the use of more renewable energy sources such as solar, wind, hydro, nuclear etc.

The cost of acting now may seem high but it will turn out to be a lot more expensive to deal with extraordinary disease burdens resulting from rising air pollution.

| |

|

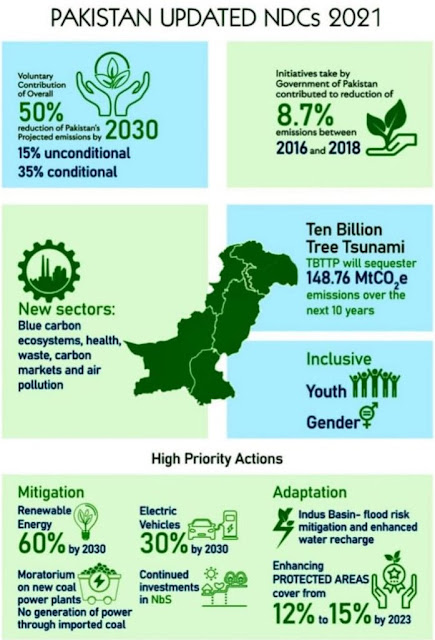

Pakistan at COP26:

Malik Amin Aslam, Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan's special assistant on climate change, said recently in an interview with CNN that his country is seeking to change its energy mix to favor green. He said Pakistan's 60% renewable energy target would to be based on solar, wind and hydro power projects, and 40% would come from hydrocarbon and nuclear which is also low-carbon. “Nuclear power has to be part of the country’s energy mix for the future as a zero energy emission source for a clean and green future,” he concluded. Here are the key points Aslam made to Becky Anderson of CNN: |

1. Pakistan wants to be a part of the solution even though it accounts for less than 1% of global carbon emissions.

Movement of pollutants does not recognize national borders. It has severe consequences for both India and Pakistan. The only way to deal with it is for the two nations to cooperate to minimize this problem.

South Asia accounts for more than a third of all PM2.5 pollution related deaths in the world. The sources of particulate pollution range from solid fuel burning to crop clearing fires and use of dirty fuels in vehicles and industries. Recognition of the growing problem is urgent. Failure to act could be very costly in terms of impact on human health and economy. Pakistan needs to follow through on its commitments made at COP26 conference recently held in Glasgow, Scotland.

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

South Asia Investor Review

Pakistan's Response to Climate Change

Pakistan Electric Vehicle Policy

Cutting Methane Emissions From Cow Burps and Farts

India's Air Most Toxic

State of Air 2017

Environmental Pollution in India

Diwali in Silicon Valley

India Leads the World in Open Defecation

Heavy Disease Burdens in South Asia

Comments

https://blogs.worldbank.org/endpovertyinsouthasia/air-pollution-aggravating-covid-19-south-asia

South Asia is also among the world’s regions most exposed to household air pollution. About 79 percent of the population in Bangladesh, 60 percent in India, and 52 percent in Pakistan are exposed to pollution from burning of solid fuels, which contribute significantly to poor health in the region.

While lockdowns have provided the temporary side benefit of cleaner air and bluer skies, previous exposure to pollution has likely made more South Asians vulnerable to contracting severe respiratory diseases, including complications from COVID-19. As of June 22, COVID-19 cases in South Asia have been rising exponentially, with more than 735,000 confirmed so far, mostly in India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh.

Medical experts place vulnerabilities related to respiratory ailments such as asthma and chronic lung disease high on the list of preexisting conditions that can make people more susceptible to COVID-19. Among the first hospitalized patients, pneumonia, sepsis, respiratory failure, and acute respiratory distress syndrome were reported as the most frequent complications.

A thick layer of smog covers Delhi due to the increase in air pollution (ANI)

https://www.livemint.com/news/india/delhi-stubble-burning-contributed-to-36-of-pollution-today-relief-expected-by-tomorrow-11636187863520.html

The national capital's Air Quality Index (AQI) continued to remain in the “severe" category on Saturday, with emissions from stubble burning contributing to 36% of the pollution, as per data from Centre-run SAFAR.

In the last 24 hours, the PM2.5 level is higher as compared to 2020 but much less than that in 2018. While stubble burning is expected to remain almost the same during the day, relief is likely from 7 November.

The Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) has also said that higher wind speeds that have picked up since the morning are likely to clear out pollutants in the air over the next two days.

According to SAFAR, without any more firecracker emissions, AQI is likely to improve to the 'very poor' category by tonight.

How Lahore Became the World’s Most Polluted Place

Unprecedented smog in the “city of gardens” comes from a confluence of familiar factors.

By Syed Mohammad Ali, a nonresident scholar at the Middle East Institute, and he teaches at Georgetown and Johns Hopkins Universities.

https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/11/29/pakistan-lahore-pollution-fossil-fuels-climate/

This past month, Lahore, Pakistan, has repeatedly topped the daily ranking of most polluted city in the world. Pollution and winter weather conditions combine to shroud the city in smog—disrupting flights, causing major road closures, and wreaking havoc on the health of its citizenry.

The problem of air pollution has been steadily growing in Lahore and many other cities in Punjab province. Punjab is the most populous province in Pakistan with an estimated population of 110 million people. Five cities in Punjab were listed among the 50 most polluted cities in the world in 2020. The situation in other major Pakistani cities, such as the coastal megalopolis of Karachi, is not much better. Yet, the current situation in Lahore is most alarming, with its fine particulate count repeatedly rising well above 40 times the World Health Organization’s air quality guideline values.

Prolonged or heavy exposure to hazardous air causes varied health complications, including asthma, lung damage, bronchial infections, strokes, heart problems, and shortened life expectancy. The Global Alliance on Health and Pollution estimated in 2019 that 128,000 Pakistanis die annually due to air pollution-related illnesses. Decision-makers have been slow to react to the pollution problem. In 2019, Pakistan’s minister of climate change infamously dubbed growing concern about the smog problem in Lahore as being a conspiratorial attempt to spread misinformation. Many officials and politicians continue blaming stubble burning by Indian farmers as the main cause for Lahore’s smog problem. Blaming India may be a tit-for-tat response to similar Indian accusations, but it not an accurate assessment. Ever-changing wind patterns during the stubble-burning season mean wind directions keep fluctuating across the India-Pakistan border. “The smog in Lahore is caused by a confluence of metrological and anthropogenic factors,” said Saleem Ali, a member of the United Nations’ International Resource Panel. Namely, temperature inversion traps pollution in the atmosphere, which—alongside seasonal crop burning on the Indian-Pakistani border—combines with other sources of year-round pollution and fog to cause a spike in pollution and winter smog.

The reasons why air quality has been steadily declining in cities like Lahore are numerous. Vehicular emissions, industrial pollution, fossil fuel-fired power plants, the burning of waste materials, and coal being burned by thousands of brick kilns spattered across the province are all part of the problem. A Food and Agriculture Organization’s source appropriation study in 2020 singles out power producers, industry, and the transport sector in particular as culprits.

-------------------

Khan’s stated environmental agenda of “greening” Pakistan has not prevented him from endorsing the multitrillion-rupee Ravi Riverfront Urban Development Project. Critics fear this project will cause massive displacement, wreak havoc to Pakistan’s longest river’s ecology, and worsen pollution and air quality in Lahore for years to come.

In the absence of comprehensive and concerted efforts to combat air pollution, Lahore, once known as the “city of gardens,” is tragically choking on toxic air. Instead of looking forward to the welcomed reprieve of winter months, Lahore’s 13 million residents now must brace themselves for another bout of smog, which has acquired the status of a “fifth season.”

India's capital Delhi has alarmingly high levels of indoor air pollution, new research has found.

The study found that the levels of PM2.5, the lung-damaging tiny particles in the air, indoors were "substantially higher" than those found on the nearest outdoor government monitors.

But despite that, most households have been unwilling to adopt defence measures, the report added.

Delhi city routinely tops the list of "world's most polluted capitals".

The study by the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago (EPIC), conducted between 2018 and 2020, surveyed thousands of Delhi households across varying socio-economic backgrounds and found that rich and poor households were equally affected.

Researchers said high-income households were 13 times more likely to own air purifiers than low-income households. Yet, the indoor air pollution levels in those homes were only 10% lower than those living in disadvantaged settings.

"In Delhi, the bottom line is - whether someone is rich or poor, no one gets to breathe clean air," said Dr Kenneth Lee, the lead author of the study. "It's a complex vicious cycle."

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that globally about seven million people die prematurely each year from diseases linked to air pollution, which it puts on a par with smoking and unhealthy eating.

Experts say most of our exposure to air pollution actually happens indoors. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the levels of indoor air pollutants can be two to five times higher than outdoors.

This is particularly a cause of concern for India, which has the world's worst air pollution. Home to 22 of the world's 30 most polluted cities, India's toxic air kills more than one million people each year.

Official government data shows Delhi recorded its worst November air in at least six years, with residents not experiencing even one "good" day of air quality through the month. Schools were shut amid worsening pollution levels and the situation was so dire that it also prompted a stern warning from India's Supreme Court.

A mix of factors like vehicular and industrial emissions, dust and weather patterns make Delhi the world's most polluted capital. The air turns especially toxic in winter months as farmers in neighbouring states burn crop stubble. And fireworks during the festival of Diwali, which happens at the same time, only worsen the air quality. Low wind speed also plays a part as it traps the pollutants in the lower atmosphere.

Yet, there is a low demand for clear air or adoption of defensive behaviours in Delhi households, according to the new report.

Researchers observed that even when people were offered a free trial of indoor air quality monitor to track pollution levels inside their homes, the take-up rates were low.

"When you do not know about the pollution levels inside your homes, you do not worry about it, and hence you are less likely to take corrective actions," said Dr Lee. "Only with increased awareness, demand for clean air may gain momentum."

Think of the fields that are on fire. They get only between 500-700mm (19-27 in) of rainfall a year. Yet, many of these fields grow a dual crop of paddy and wheat. Paddy alone needs about 1,240mm (48.8 in) of rainfall each year, and so, farmers use groundwater to bridge the gap.

The northern states of Punjab and Haryana, which grow large amounts of paddy, together take out roughly 48 billion cubic metres (bcm) of groundwater a year, which is not much less than India's overall annual municipal water requirement: 56bcm. As a result, groundwater levels in these states are dropping rapidly. Punjab is expected to run out of groundwater in 20-25 years from 2019, according to an official estimate.

The burning fields is a symptom of the deteriorating relationship between India and its water.

Long ago, farmers grew crops based on locally available water. Tanks, inundation canals and forests helped smoothen the inherent variability of India's tempestuous water.

But in the late 19th Century, the land began to transform as the British wanted to secure India's north-western frontier against possible Russian incursion. They built canals connecting the rivers of Punjab, bringing water to a dry land. They cut down forests, feeding the wood to railways that could cart produce from the freshly watered fields. And they imposed a fixed tax payable in cash that made farmers eager to grow crops that could be sold easily. These changes made farmers believe that water could be shaped, irrespective of local sources - a crucial change in thinking that is biting us today.

After independence from the British in 1947, repeated droughts made the Indian government succumb to the lure of the "green revolution".

Until then, rice, a water-hungry crop, was a marginal crop in Punjab. It was grown on less than 7% of the fields. But beginning in the early 1960s, paddy cultivation was encouraged by showing farmers how to cheaply and conveniently tap into a new, seemingly-endless source of water that lay underground.

The flat power tariffs to run borewells were cheapened and finally not paid - removing any incentive to conserve water. Water did not need to be managed, farmers were taught, only extracted. In the heady first years of the revolution, fields began to churn out paddy and wheat, and India became food-secure. But after a couple of decades, the water began to sputter.

To conserve groundwater, a 2009 law forbade farmers from sowing and transplanting paddy before a pre-determined date based on the onset of the monsoon. The aim was to make the borewells run less in the peak summer months.

But the delay in paddy planting shrunk the gap between the paddy harvest and sowing of wheat. And the quickest way to clear the fields was to burn them, giving rise to the smoky plumes that add to northern India's air pollution.

So, the toxic smog is but a visible symbol of India's trainwreck of a relationship with its water.

A ragpicker separates items at the edge of a fire at the Bhalswa landfill in New Delhi, India, Wednesday, April 27, 2022. The landfill that covers an area bigger than 50 football fields, with a pile taller than a 17-story building caught fire on Tuesday evening, turning into a smoldering heap that blazed well into the night. India's capital, which like the rest of South Asia is in the midst of a record-shattering heat wave, was left enveloped in thick acrid smoke.

Authorities in India stepped up efforts on Friday to address deteriorating air quality as farmers burning crop stubble and calmer winter winds left a thick blanket of haze and smog to choke residents across the Delhi capital region. Factories, construction sites and primary schools were ordered to shut down and Delhi authorities urged people to work from home as dangerous fine particle pollution filled the air.

Delhi's 24-hour average air quality index (AQI), which measures the concentration of very fine particles know as PM2.5 in the air — particularly harmful pollutants as they're easily inhaled and can settle deep in the lungs — crossed 470 on Friday, per the state-run Central Pollution Control Board.

Anything over 300 is classed as "hazardous" on the international AQI rating system, and at "severe" levels, air pollution "affects healthy people and seriously impacts those with existing diseases." On Friday, many parts of Delhi recorded an AQI of more than 600.

Authorities also restricted the operation of diesel-powered vehicles and sent out trucks equipped with water sprinklers and anti-smog guns to try to control the smog.

"We are also mulling over implementing the odd-even scheme for the running of vehicles," Arvind Kejriwal, the Chief Minister of Delhi, said. That would see about half of Delhi's privately owned vehicles ordered off the roads, with odd and even-numbered license plates allowed to operate on alternating days.

Even the air quality monitors installed at the U.S. Embassy in Delhi, which sits in one of the cleanest and greenest patches in the city, registered an AQI over 360 on Friday, well into the most dire, "hazardous" level on the AQI chart displayed on the embassy's website.

Residents of the Indian capital weren't likely to see much improvement quickly, with weather conditions expected to remain calm and the seasonal crop stubble burning likely to continue.

India's Environment Minister, Bhupender Yadav, on Wednesday blamed the opposition-run northern state of Punjab for failing to stop farmers burning off the remains of their harvested summer crops.

"There is no doubt over who has turned Delhi into a gas chamber," Yadav said in a tweet.

Punjab's top politician, Bhagwant Mann, defended his administration, saying it only took office half a year ago and calling for a collaborative effort by state and federal authorities to address the problem.

The Delhi government is following a Graded Response Action Plan (GRAP) to combat air pollution in the city. The stricter measures were taken Friday as the average air quality worsened to "Severe Plus," with the AQI over 450.

"It is the responsibility of all of us to take initiative at every level to stop pollution," said Delhi's state environment minister Gopal Rai earlier in the week.

The mild winter months are always busy for Mumbai-based pulmonologist Revathy K, but these past few months have been especially hectic. In November, a sudden drop in ocean temperatures slowed the winds that normally shift the city’s construction dust, debris, and traffic fumes. The Bandra-Worli Sea Link, a bridge that connects the center of the city to its northern suburbs, disappeared behind a curtain of smog as the city’s air quality dropped to “very poor,” briefly overtaking Delhi, the world’s most polluted city.

“A lot of patients were coming in with a wheeze,” K says, something she usually sees in patients who have asthma or smoking-related disorders. Within the span of a few months, from November through January, Mumbai doctors reported seeing a rise in chronic and persistent coughs, alongside the annual flu season. “These are patients who’ve never had any allergic symptoms in the past but are now coming in with [symptoms resembling] acute bronchitis,” says K (who, like many Indians, uses an initial as her last name.)

India’s air pollution is a rolling disaster that shows no sign of slowing down. A 2022 report by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air think tank found that “almost the entire population of India” is exposed to air pollution above the guidelines set by the World Health Organization. In 2019, air pollution killed an estimated 1.6 million Indians.

As attempts to fix the problem at the source fail, a new kind of inequality is taking hold in Indian cities. Facing potentially deadly air quality outside, wealthier Indians are paying to breathe free, creating a booming market for air purifiers that is forecast to grow 35 percent to $597 million by 2027. But in a country already economically divided along caste, gender, and religious lines, where 63 percent of people pay for health care out-of-pocket and the top 10 percent of the population hold 77 percent of the wealth, paying for breathable air isn’t an option for most.

“We are normalizing a world that hardly values nature and natural rights—basic necessities like clean drinking water, fresh and unpolluted air, space to walk for pedestrians is neither part of urban planning nor [do they] concern our collective conscience,” says Suryakant Waghmore, professor of sociology at the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay. Waghmore says air purifiers purify air for the privileged “while the public is left to decay and degrade.”

As a cold spell swept through Mumbai in January and people donned sweaters and balaclavas to keep warm, a dusty haze hung in the air, occasionally caking onto leaves and piling into mounds on street corners. Roads remained choked with traffic, and the city’s poorer residents resorted to dumpster fires, burning scraps of wood, rubber, and plastic to stay warm.

Timothy Dmello, who spends 12 hours a day outdoors as a paid dog walker, says he started to notice the worsening air pollution as he went up and down the Carter Road promenade, a palm-tree-lined stretch flanked by Bollywood celebrities’ apartments looking out onto the Arabian Sea. He says you can’t see the horizon clearly.

Dmello’s wife is on kidney dialysis; he took a job as a dog walker because the flexible hours meant he could spend more time with her and their 14-year-old daughter. At home, dust from outside builds up, while outside he’s exposed to fumes and particulates. Demello says that sometimes breathing is a problem.

He has seen air purifiers in the hospital, but the cost—cheaper models start at 6,000 rupees ($72)—is out of reach. Like most people he knows, he fell ill with a cough and cold this winter and couldn’t work.

Sixty percent of India’s nearly 1.3 billion people live on less than $3.10 a day, below the World Bank’s median poverty line. Not counting farm workers, 18 percent of the country’s population work outdoors.

Exposure to high levels of ambient PM 2.5 (particulate matter under 2.5 micrometers, which gets stuck in people’s lungs) can cause deadly illnesses such as lung cancer, strokes, and heart disease. Deaths linked to PM 2.5 pollution have more than doubled in the past 20 years, claiming 979,900 lives in 2019. What’s more, according to the World Air Quality Report 2022, air pollution costs India $150 billion a year.

In 2019, when 102 cities in India failed to meet the country’s air pollution standards, the government launched a National Clean Air Programme. Less than five years later, the number of failing cities has grown to 132.

National and state governments have tried unsuccessfully to address the air quality crisis. In Delhi, the Aam Aadmi Party, which runs the city, tried an “odd-even” scheme in 2016, when the air quality dropped considerably. Private vehicles with registration plates ending in odd numbers could drive on odd dates, and those with even numbers on even dates. Environmentalists say it had minimal impact on air pollution levels. Delhi, as well as nearby Gurugram, which is a major tech hub, have also tried technological solutions. In 2021, the Supreme Court ordered the Delhi government to install two massive, 24-meter-high “smog towers” to filter particulates from the air, while Gurugram has put outdoor air purifiers in place. In February, Mumbai’s civic body, the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation, announced plans to install 14 outdoor air purifiers across the city.

However, experts believe these measures are a dead end. “Purifiers don’t work,” says Ronak Sutaria, founder of Respirer Living Sciences, an urban data startup that monitors air pollution. “I think there’s broad consensus amongst the research in the scientific community that purifiers do not solve the problem.”

Outdoor purifiers are a last resort when other methods of controlling pollution have failed, according to Pallav Purohit, a senior research scholar at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis in Austria. “It makes sense to use air purifiers only when traditional methods of pollution control are insufficient,” he says. “The shortfall with most outdoor air purification systems is a limited area of coverage, limited efficacy, and high cost.”

Purohit says the purifiers create narrow columns of purified air that only really benefit people who are close to them for an extended period of time.

Following Mumbai’s air quality crisis this winter, critics accused the Maharashtra Pollution Control Board of moving air quality sensors to “cleaner” parts of the city.

Purohit says the purifiers create narrow columns of purified air that only really benefit people who are close to them for an extended period of time.

Following Mumbai’s air quality crisis this winter, critics accused the Maharashtra Pollution Control Board of moving air quality sensors to “cleaner” parts of the city.

Meanwhile, India’s wealthier residents have taken matters into their own hands. Air purifier brands have become a common topic of conversation among middle-class residents. People who can afford to do so move from air-purified homes (where each room often has its own purifier) to air-purified shops and malls, driven in air-purified cars. Brands have enlisted cricket stars and Bollywood celebrities, advertising in English-language newspapers, on social media, and on billboards.

If the combination of advertisements and news coverage is to be believed, breathing air in India’s capital is equivalent to 50 cigarettes a day during Diwali, a Hindu festival where many people burst firecrackers, and 10 cigarettes a day during the winter. For an Indian Independence Day advert, Sharp suggests “Impurities Quit India,” referring to the “Quit India” movement from India’s freedom struggle. News articles meet every spike in poor air quality with air purifier advice: “Delhi air quality turns severe: 5 Air purifiers that will help you breathe clean air,” reads one; “Planning To Buy An Air Purifier Amid Falling AQI? Know the Costs, Other Factors” reads another.

Deekshith Vara Prasad, founder and CEO of Indian-made air purifier AirOK Technologies, says his company’s sales have grown 18 percent since 2018. (AirOK Technologies’ air purifiers are largely used in hospitals and offices.)

Prasad says surging demand has led to substandard products in the market. To work on the air in India’s cities, purifiers need to filter out fine particulate matter, fungus, bacteria, viruses, and toxic gasses like sulfur and nitrous oxides. There are “hundreds” of pollutants, he says. “If I remove two pollutants, I can claim I ‘remove pollutants.’”

The borders of private spaces, like offices and, increasingly, hotels—which sometimes market themselves based on their air purification—are a stark illustration of the unequal access to clean air. Door attendants, valets, bellhops, and security guards working the entrances and exits to these buildings don’t breathe the purified air available to those inside.

Waghmore says this division intersects with India’s social inequalities around status and caste and that air purifiers only consolidate the ideology of “purity” as something that is central to the lives of dominant caste.

Such inequality has severe consequences, as those from disadvantaged castes already face considerable barriers in accessing health care.

Waghmore says the heightened sense of privileged individualism—where the rich have the means to fend for themselves—“has the worst consequences in poor countries, where governments are yet to invest morally and economically in public infrastructure and transport to counter environmental degradation.”

K, who regularly treats those suffering from India’s air pollution inequality, puts it more succinctly. “I don’t think people should live with this,” she say, adding that everyone needs to take demand solutions. “If you don’t get something as basic as fresh air, then what’s the point of living in our country?”

Residents of Paris, London, Los Angeles and Hong Kong are breathing cleaner air than a year ago, while N’Djamena, Baghdad and New Delhi are suffering higher levels of pollution, the latest report on global air quality shows.

Roughly 90 per cent of the world’s population is still breathing air that poses a risk to health but the gap between high and low income cities is widening, the annual study by IQAir, the Swiss-based air technology group found, using 30,000 ground level sensors from more than 7,000 cities.

The study measured the concentration of fine particulate matter with diameters of up to 2.5 microns, known as PM2.5, one of the most hazardous pollutants as it may be able to enter the bloodstream.

In richer countries, air quality was improved where industry was complying with stricter World Health Organization guidelines, and transport was being electrified, it concluded, but developing countries were struggling.

“Biomass and agricultural burning are the number one reason for stubbornly high air pollution levels in the developing world,” said Frank Hammes, IQAir chief executive.

In Europe, where Berlin and Rome had slightly worse air quality levels in 2022, household burning of wood accounted for a large proportion of winter smog.

China had managed to achieve impressive reductions in air pollution for the past seven years, Hammes said, based on a crackdown on polluting industry and a focus on renewable energy and electric vehicles, though continued burning of coal still caused serious air pollution.

In the most recent year, China’s air quality improved as extensive Covid lockdowns suppressed economic activity, leading to lower emissions.

“In 2023, it remains to be seen if China can further reduce air pollution, or if the pressure of increased economic activity leads to stagnation or an increase in air pollution,” Hammes cautioned.

The WHO estimates that poor air quality accounts for 7mn preventable deaths a year, while the World Bank has put the economic cost at more than $8tn.

New Delhi and Baghdad’s concentration of pollutants in 2022 were almost 18 times higher than the maximum safe level recommended by the WHO.

N’Djamena in Chad, one of the poorest countries in the world, earned the dubious accolade of being the most polluted capital, replacing New Delhi even though air quality there also continued to deteriorate. The surge in PM2.5 concentration in N’Djamena was attributed to massive dust storms from the Sahara Desert, the report found.

India remains host to 12 of the top 15 most polluted cities in the central and south Asia regions.

Vietnam’s capital Hanoi reported the second worst air quality in south-east Asia and was in the bottom 18 globally. Vietnam has been expanding its industrial activity rapidly in recent years as big tech companies such as Apple, Google, Dell and their suppliers invest in new factories to diversify away from China.

Several Middle Eastern capitals ranked among the 20 most polluted cities globally. These included Abu Dhabi, Riyadh and Doha, which all saw air quality worsen in 2022.

Meanwhile, Canberra in Australia overtook Nouméa, in the Pacific island of New Caledonia, to report the world’s best air quality last year. Fewer fires and dust storms helped to deliver its residents cleaner air, researchers found.

Other nations among the 13 out of 131 surveyed that met WHO’s air quality guidelines included Guam, New Zealand, Estonia, and Finland. Of the cities surveyed, Hamilton in Bermuda, Puerto Rico’s San Juan and Reykjavik in Iceland had the freshest air.