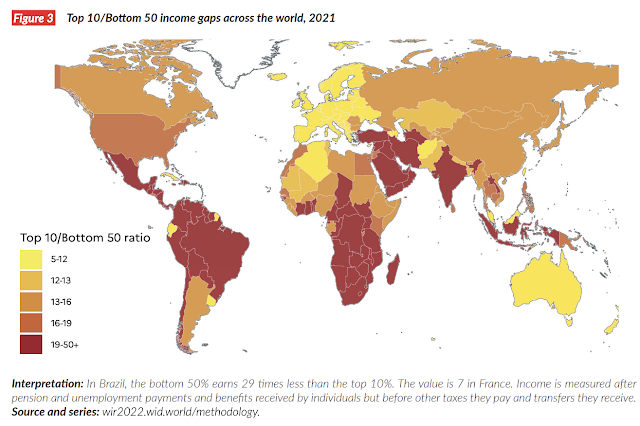

India Is Among The World's Most Unequal Countries

India is one of the most unequal countries in the world, according to the World Inequality Report 2022. There is rising poverty and hunger. Nearly 230 million middle class Indians have slipped below the poverty line, constituting a 15 to 20% increase in poverty. India ranks 94th among 107 nations ranked by World Hunger Index in 2020. Other South Asians have fared better: Pakistan (88), Nepal (73), Bangladesh (75), Sri Lanka (64) and Myanmar (78) – and only Afghanistan has fared worse at 99th place. Meanwhile, the wealth of Indian billionaires jumped by 35% during the pandemic.

|

| Income Inequality Map. Source: World Inequality Report 2022 |

Unemployment Crisis:

India lost 6.8 million salaried jobs and 3.5 million entrepreneurs in November alone. Many among the unemployed can no longer afford to buy food, causing a significant spike in hunger. The country's economy is finding it hard to recover from COVID waves and lockdowns, according to data from multiple sources. At the same time, the Indian government has reported an 8.4% jump in economic growth in the July-to-September period compared with a contraction of 7.4% for the same period a year earlier.

|

| Income Inequality By Regions. Source: World Inequality Report 2022 |

|

| Income & Wealth Inequality. Source: World Inequality Report 2022 |

Rising Poverty:

Nearly 230 million middle class Indians have slipped below the poverty line, constituting a 15 to 20% increase in poverty since Covid-19 struck last year, according to Pew Research. Middle class consumption has been a key driver of economic growth in India. Erosion of the middle class will likely have a significant long-term impact on the country's economy. “India, at the end of the day, is a consumption story,” says Tanvee Gupta Jain, UBS chief India economist, according to Financial Times. “If you never recovered from the 2020 wave and then you go into the 2021 wave, then it’s a concern.”

Increasing Hunger:

A United Nations report on inequality in Pakistan published in April 2021 revealed that the richest 1% Pakistanis take 9% of the national income. A quick comparison with other South Asian nations shows that the 9% income share for the top 1% in Pakistan is lower than 15.8% in Bangladesh and 21.4% in India. These inequalities result mainly from a phenomenon known as "elite capture" that allows a privileged few to take away a disproportionately large slice of public resources such as public funds and land for their benefit.

|

| Income Distribution by Quintiles in Pakistan. Source: UNDP |

Elite Capture:

Elite capture, a global phenomenon, is a form of corruption. It describes how public resources are exploited by a few privileged individuals and groups to the detriment of the larger population.

A recently published report by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) has found that the elite capture in Pakistan adds up to an estimated $17.4 billion - roughly 6% of the country's economy.

Pakistan's most privileged groups include the corporate sector, feudal landlords, politicians and the military. The UN Development Program's NHDR for Pakistan, released last week, focused on issues of inequality in the country of 220 million people.

Ms. Kanni Wignaraja, assistant secretary-general and regional chief of the UNDP, told Aljazeera that Pakistani leaders have taken the findings of the report “right on” and pledged to focus on prescriptive action. “My hope is that there is strong intent to review things like the current tax and subsidy policies, to look at land and capital access", she added.

|

| Inequality in Pakistan. Source: UNDP |

Income Inequality:

The richest 1% of Pakistanis take 9% of the national income, according to the UNDP report titled "The three Ps of inequality: Power, People, and Policy". It was released on April 6, 2021. Comparison of income inequality in South Asia reveals that the richest 1% in Bangladesh and India claim 15.8% and 21.4% of national income respectively.

In addition to income inequality, the UNDP report describes the inequality of opportunity in terms of access to services, work with dignity and accessibility. It is based on exhaustive statistical analysis at national and provincial levels, and includes new inequality indices for child development, youth, labor and gender. Qualitative research, through focus groups with marginalized communities, has also been undertaken, and the NHDR 2020 Inequality Perception Survey conducted. The NHDR 2020 has been guided by a diverse panel of Advisory Council members, including policy makers, development practitioners, academics, and UN representatives.

Summary:

Neoliberal policies in emerging markets like India have spurred economic growth in last few decades. However, the gains from this rapid growth have been heavily skewed in favor of the rich. The rich have gotten richer while the poor have languished. The average per capita income in India has tripled in recent decades but the minimum dietary intake has fallen. According to the World Food Program, a quarter of the world's undernourished people live in India. The COVID19 pandemic has further widened the gap between the rich and poor.

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

South Asia Investor Review

Pakistan Among World's Largest Food Producers

Food in Pakistan 2nd Cheapest in the World

Indian Economy Grew Just 0.2% Annually in Last Two Years

Pakistan to Become World's 6th Largest Cement Producer by 2030

Pakistan's 2012 GDP Estimated at $401 Billion

Pakistan's Computer Services Exports Jump 26% Amid COVID19 Lockdown

Coronavirus, Lives and Livelihoods in Pakistan

Vast Majority of Pakistanis Support Imran Khan's Handling of Covid19 Crisis

Pakistani-American Woman Featured in Netflix Documentary "Pandemic"

Incomes of Poorest Pakistanis Growing Faster Than Their Richest Counterparts

Can Pakistan Effectively Respond to Coronavirus Outbreak?

How Grim is Pakistan's Social Sector Progress?

Pakistan's Sehat Card Health Insurance Program

Trump Picks Muslim-American to Lead Vaccine Effort

COVID Lockdown Decimates India's Middle Class

Pakistan Child Health Indicators

Pakistan's Balance of Payments Crisis

How Has India Built Large Forex Reserves Despite Perennial Trade Deficits

India's Unemployment and Hunger Crises"

PTI Triumphs Over Corrupt Dynastic Political Parties

Strikingly Similar Narratives of Donald Trump and Nawaz Sharif

Nawaz Sharif's Report Card

Riaz Haq's Youtube Channel

Comments

How the State Has Stifled Growth

By Arvind Subramanian and Josh Felman

January/February 2022

https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/india/2021-12-14/indias-stalled-rise

As growth slowed, other indicators of social and economic progress deteriorated. Continuing a long-term decline, female participation in the labor force reached its lowest level since Indian independence in 1948. The country’s already small manufacturing sector shrank to just 13 percent of overall GDP. After decades of improvement, progress on child health goals, such as reducing stunting, diarrhea, and acute respiratory illnesses, stalled.

And then came COVID-19, bringing with it extraordinary economic and human devastation. As the pandemic spread in 2020, the economy withered, shrinking by more than seven percent, the worst performance among major developing countries. Reversing a long-term downward trend, poverty increased substantially. And although large enterprises weathered the shock, small and medium-sized businesses were ravaged, adding to difficulties they already faced following the government’s 2016 demonetization, when 86 percent of the currency was declared invalid overnight, and the 2017 introduction of a complex goods and services tax, or GST, a value-added tax that has hit smaller companies especially hard. Perhaps the most telling statistic, for an economy with an aspiring, upwardly mobile middle class, came from the automobile industry: the number of cars sold in 2020 was the same as in 2012.

--------

Adding to a decade of stagnation, the ravages of COVID-19 have had a severe effect on Indians’ economic outlook. In June 2021, the central bank’s consumer confidence index fell to a record low, with 75 percent of those surveyed saying they believed that economic conditions had deteriorated, the worst assessment in the history of the survey.

After it gained independence in 1947, India’s soaring population—made possible by advances in medicine and disease control—seemed to doom it to poverty and hunger. Droughts in the mid-1960s raised the specter of famine. In 1966 the U.S. shipped one-fourth of its wheat output to India to avert mass starvation. Paul Ehrlich’s 1968 best-seller, “The Population Bomb,” predicted that hundreds of millions would starve and that by 1977 India could fall apart “into a large number of starving, warring minor states.”

----------

As in many countries, urbanization, rising income and female literacy, and increased contraception have led to plummeting fertility. But the biggest reason for the decline, according to Mr. Eberstadt, is hard to measure: Indian women want fewer babies.

In 1960 the average Indian woman would bear six children during her lifetime. By 2005 this had fallen to three. Urban India now has a fertility rate of 1.6, comparable to the European Union. And unlike China, whose government enforced a draconian one-child policy, India has achieved this largely without coercion. A harsh sterilization drive by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in the mid-1970s led to her crushing electoral defeat in 1977. No Indian government tried to force the matter again.

Though India may have dodged mass famine, its massive population still poses challenges. Optimists claim the country’s skew toward youth provides a demographic dividend: a large working-age cohort to support relatively few retirees.

But such sunny prognostications present only half the picture. Thanks to uneven development, in the coming decades India will house an unprecedented experiment: hundreds of millions of college graduates living among hundreds of millions of illiterates. “The education gap in India could generate an income distribution that will make Manhattan look like Sweden,” says Mr. Eberstadt.

Regional disparities complicate things further. The relatively well-educated coastal states of the south already have fertility rates well below replacement levels. Birthrates in the poor and populous Hindi heartland have fallen too, but not nearly as sharply. Three of them—Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Jharkhand—remain above replacement levels.

“To oversimplify, you have a baby factory in the north and a jobs factory in the south,” says Mr. Eberstadt. “But there’s a mismatch in educational attainment between a rising cohort in the north and the needs of the economy emerging in the south.” Kerala, in the south, has a literacy rate of 96%. Bihar, in the north, is 71%.

Then there’s the most sensitive question: political representation. In the relative weight of its states, India’s Parliament has remained frozen since the 1971 census. The average parliamentarian from Uttar Pradesh represents three million people, while a counterpart from Tamil Nadu represents 1.8 million. A 2019 report by Carnegie Endowment scholars Milan Vaishnav and Jamie Hintson calculated that if Parliament were reapportioned according to the likely population in 2026, the five southern states would send 26 fewer representatives to the 545-seat Parliament. The four most populous Hindi heartland states would add 31 seats.

If India is lucky, it will defuse these problems as successfully as it dealt with food shortages a generation ago. But though the population bomb failed to explode, it doesn’t mean India is safe from other ticking time bombs.

Car sales in 2010 2.5 million

Car sales in 2021 2.7 million

Motorcycle sales 2010 12 million

Motorcycle sales 2021 15 million

Pakistan car sales grew from 137,000 in 2010 to 198,000 in 2021

Pakistan motorcycle sales grew from 700,000 in 2010 to 2.4 million in 2021

Pakistan car sales grew from 137,000 in 2010 to 198,000 in 2021

Pakistan motorcycle sales grew from 700,000 in 2010 to 2.4 million in 2021

Manufacturing accounts for nearly 17% of India's GDP, but the sector has seen employment decline sharply in last 5 years - from employing 51 million Indians in 2016-17 to reach 27.3 million in 2020-21

https://www.business-standard.com/article/economy-policy/ceda-cmie-bulletin-manufacturing-employment-halves-in-five-years-121050601086_1.html

With the second wave of the coronavirus pandemic battering India at present, the Indian economic outlook looks bleak for the second year in a row. In 2020-21, India’s real GDP growth is estimated to be minus 8 per cent. This would also put pressure on India’s employment numbers. In previous bulletins, we have analysed the impact of Covid-19 pandemic on employment, individual and household incomes and expenditures in 2020.

In this CEDA-CMIE Bulletin, we try to take a longer-term view of sector-wise employment in India. We base this on CMIE’s monthly time-series of employment by industry going back to the year 2016. For this bulletin, we have focused on seven sectors – agriculture, mines, manufacturing, real estate and construction, financial services, non-financial services, and public administrative services. These sectors make up for 99 per cent of total employment in the country.

In figure 2 and 3 (below), we look at four sectors. These are agriculture, financial services, non-financial services, and public administrative services. Non-financial services exclude public administrative services and defense services. Together, these accounted for 69 per cent of total employment in 2016-17 and 78 per cent in 2020-21.

The agriculture sector employed 145.6 million people in 2016-17. This increased by 4 per cent to reach 151.8 million in 2020-21. While it constituted 36 per cent of all employment in 2016-17, the figure rose to 40 per cent in 2020-21, underlining the sector’s importance for the Indian economy. Employment in agriculture has been on the rise over the last two years with year-on-year (YoY) growth rates of 1.7 per cent in 2019-20 and 4.1 per cent in 2020-21.

119.7 million Indians were employed in the non-financial services in 2016-17 (excluding those in public administrative services and defense services) (Figure 3). This number rose by 6.7 per cent to reach 127.7 million in 2020-21. The financial services sector employed 5.3 million people in 2016-17 and this grew by 9 per cent to 5.8 million in 2020-21.

Public administrative services employed 9.8 million people in 2016-17 but it decreased by 19 per cent to 7.9 million in 2020-21.

In figure 4, we look at employment in manufacturing, real estate & construction, and mining sectors. Together these sectors accounted for 30 per cent of all employment in 2016-17 which came down to 21 per cent in 2020-21.

Manufacturing accounts for nearly 17 per cent of India’s GDP but the sector has seen employment decline sharply in the last 5 years. From employing 51 million Indians in 2016-17, employment in the sector declined by 46 per cent to reach 27.3 million in 2020-21. This indicates the severity of the employment crisis in India predating the pandemic.

On a YoY basis, it employed 32 per cent fewer people in 2020-21 over 2019-20. It had seen a growth of 1 per cent (YoY) in 2019-20. This has happened despite the Indian government’s push to improve manufacturing in the country with the ‘Make in India’ project. Under the project, India sought to create an additional 100 million manufacturing jobs in India by 2022 and to increase manufacturing’s contribution to GDP to 20 per cent by 2025.

Instead of increasing employment in the sector, we have seen a sharp decline over the last 5 years. When we look closely at industries that make the manufacturing sector, we find that this is a secular decline in employment across all sub-sectors, except chemical industries.

All sub-sectors within manufacturing registered a longer-term decline.

https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/op-ed/the-nmp-is-hardly-the-panacea-for-growth-in-india/article37956016.ece

As the Government has also shown, there are out-of-the-box policy initiatives to revamp public sector businesses

The National Monetisation Pipeline (NMP) envisages an aggregate monetisation potential of ₹6-lakh crore through the leasing of core assets of the Central government in sectors such as roads, railways, power, oil and gas pipelines, telecom, civil aviation, shipping ports and waterways, mining, food and public distribution, coal, housing and urban affairs, and stadiums and sports complexes, to name some sectors, over a four-year period (FY2022 to FY2025). But the point is that it only underscores the need for policy makers to investigate the key reasons and processes which led to once profit-making public sector assets becoming inefficient and sick businesses.

------------------

Congress leader Sachin Pilot on Wednesday slammed the Central government over National Monetisation Pipeline (NMP) by saying that the new scheme will create monopoly and duopoly in the economy.

https://www.business-standard.com/article/current-affairs/nmp-will-create-monopoly-duopoly-in-our-economy-says-sachin-pilot-121090200108_1.html

Addressing a press conference in Bengaluru, Pilot questioned the government's decision to "lease core strategic assets of the country to private entities".

"The government said that NMP will get revenue of Rs 6 lakh crores for the next four years. The money that they will raise, will it go to fulfil the Rs 5.5 lakh crores deficit that we are running today or is it there to boost revenue," he stated.

"There is already a problem of unemployment in our country. When private entities take over the assets like railways, telecom and aviation, they will certainly lay off more people to make profits, which means more unemployment," he added.

Pilot further said that handing over important assets of the country to a handful of people will create a monopoly and duopoly in the economy.

The Congress MLA asserted that the NMP poses serious questions on the country's integrity and security. "I want to ask what stops the international funds to make an investment and take a stake in these important assets," he stated.

"There are many countries that forbid Chinese entities to bid for telecom tower or fibre optical cable. I want to question the government what safeguards have been placed in NMP to stop inappropriate entities from bidding for our core strategic assets," he added.

Pilot called the government's decision regarding NMP as 'unilateral' that happened without any discussion with trade unions, stakeholders or the Opposition. He further questioned the transparency of the whole process and how it is going to benefit people.

"Will the money raised be used to double farmers' income or to give Rs 15 lakhs to every Indian citizen as promised by the government? Or will it be used to make a building complex or in some vanity project," he questioned.

https://www.nytimes.com/2021/12/23/opinion/culture/holiday-feasting-rich-poor.html

There’s a long tradition among social thinkers and policymakers of treating workers as walking, talking machines that turn calories into work and work into commodities that get sold on the market. Under capitalism, food is important because it provides fuel to the work force. In this line of thinking, enjoyment of food is at best a distraction and often a dangerous invitation to indolence.

The scolding American lawmakers who want to forbid the use of food stamps to purchase junk food are part of a long lineage that goes back to the Victorian workhouses, which made sure that the food was never inviting enough to encourage sloth. It is the continuing obsession with treating working-class people as efficient machines for turning nutrients into output that explains why so many governments insist on giving bags of grain to the poor instead of money that they might waste. This infantilizes the poor and, except in very special circumstances, it does nothing to improve nutrition.

The pleasure of eating, to say nothing of cooking, has no place in this narrative. And the idea that if working people knew what was good for them, they’d simply seek out more food as fuel is a woefully limited view of the eating experience of most of the world. As anybody who has been poor or has spent time with poor people knows, eating something special is a source of great excitement.

As it is for everyone. Standing at the end of this very dark and disappointing year, almost two years into a pandemic, we all need the joy of a feast — whether actual or metaphorical.

Every village has its feast days and its special festal foods. Somewhere goats will be slaughtered, somewhere ceremonial coconuts cracked. Perhaps fresh dates will be piled on special plates that come out once a year. Maybe mothers will pop sweetened balls of rice into the mouths of their children.

Friends and relatives will come over to help roast an entire camel for Eid; to share scoops of feijoada, that wonderful Brazilian stew of beans simmered with off-cuts, from pig’s ears to cow’s tongue; to pinch the dumplings for the Lunar New Year; to fold the delicate edges of sweet coconut-stuffed Maharashtrian karanji, to be fried under the watchful eye of the matriarch. The feast’s inspiration might be religious, but it could as well be a wedding, a birth, a funeral or a harvest.

-------

This feasting season, that momentary joy is likely to feel especially essential. Most of us have had reasons to worry — about ourselves, about our children and parents, about where the world is headed. This year many lost friends and relatives, jobs and businesses. Many spent months working in Zoom-land, languishing even as they counted themselves lucky to be employed.

Baldev Kumar threw his head back and laughed at the mention of India’s resurgent GDP growth. The country’s economy clocked an 8.4-percent uptick between July and September compared with the same period last year. India’s Home Minister Amit Shah has boasted that the country might emerge as the world’s fastest-growing economy in 2022.

Kumar could not care less.

As far as he was concerned, the crumpled receipt in his hand told a different story: The tomatoes, onions and okra he had just bought cost nearly twice as much as they did in early November. The 47-year-old mechanic had lost his job at the start of the pandemic. The auto parts store he then joined shut shop earlier this year. Now working at a car showroom in the Bengaluru neighbourhood of Domlur, he is worried he might soon be laid off as auto sales remain low across India.

He has put plans for his daughter’s wedding on hold, unsure whether he can foot the bill. He used to take a bus to work. Now he walks the five-kilometre (three-mile) distance to save a few rupees. “I don’t know which India that’s in,” he said, referring to the GDP figures. “The India I live in is struggling.”

Kumar wasn’t exaggerating – even if Shah’s prognosis turns out to be correct.

Asia’s third-largest economy is indeed growing again, and faster than most major nations. Its stock market indices, such as the Sensex and Nifty, are at levels that are significantly higher than at the start of 2021 – despite a stumble in recent weeks. But many economists are warning that these indicators, while welcome, mask a worrying challenge – some describe it as a crisis – that India confronts as it enters 2022.

November saw inflation rise by 14.23 percent, building on a pattern of double-digit increases that have hit India for several months now. Fuel and energy prices rose nearly 40 percent last month. Urban unemployment – most of the better-paying jobs are in cities – has been moving up since September and is now above 9 percent, according to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, an independent think-tank. “Inflation hits the poor the most,” said Jayati Ghosh, a leading development economist at New Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University.

All of this is impacting demand: Government data shows that private consumption between April and September of 2021 was 7.7 percent lower than in 2019-2020. The economic recovery from the pandemic has so far been driven by demand from well-to-do sections of Indian society, said Sabyasachi Kar, who holds the RBI Chair at the Institute of Economic Growth. “The real challenge will start in 2022,” he told Al Jazeera. “We’ll need demand from poorer sections of society to also pick up in order to sustain growth.”

-------------

“The decimation of MSMEs is why we’re seeing core inflation, and we should be very worried,” said economist Pronab Sen, former chief statistician of India, referring to an inflation measure that leaves out food and energy because of their volatile price shifts. India’s core inflation stood at more than 6 percent in October. The level of competition in the market has also dramatically shrunk, he said. “Pricing power has shifted to a small number of large companies,” Sen told Al Jazeera. “And it is their exercise of this power that is leading to core inflation.”

When fuel prices rise globally – and subsequently in India – some inflation is unavoidable. But a competitive market usually forces companies to absorb much of that burden in their margins. Without that competition, Sen said, it is easier for firms to pass more of the increased costs on to consumers.

MSMEs have long been the backbone of the Indian labour market, employing 110 million people. Their struggles are a key reason for India’s failure to reduce unemployment rates, Sen added.

Protests continued across the country and outside major hospitals in New Delhi on Tuesday, a day after police officers in the capital detained more than 2,500 protesting doctors who were walking toward the residence of India’s health minister.

--------

Medical students from across India have joined the protests, which intensified two weeks ago and have grown angrier after police officers were seen beating junior doctors during a march on Monday.

The New Delhi government has expressed concern over a rising number of coronavirus cases and announced new measures, including a nighttime curfew, to slow the spread of the virus. While the country’s overall case count remains low, daily infections in the capital region have risen by more than 300 percent over the past two weeks, according to the Our World in Data Project at the University of Oxford. It is unclear how many of the new cases are of the Omicron variant.

As the doctors’ strike has stretched on, drawing in recent graduates and tens of thousands of the more than 70,000 doctors who work at government medical facilities nationwide, emergency health services have been the worst hit.

Videos from major state-run hospitals in New Delhi have shown patients on stretchers lying unattended outside emergency rooms. Many Indians rely on state medical facilities for care because of the high cost of treatment at private hospitals.

The protests were triggered by delays in placing medical school graduates in jobs at government health facilities, as India’s Supreme Court considers an affirmative action policy aimed at increasing the share of positions reserved for underrepresented communities. Protesting doctors say they are not against the quotas, but want the court to expedite its decision so that graduates can begin their jobs.

During India’s catastrophic coronavirus wave earlier this year, doctors and other medical personnel found themselves short-handed and underfunded as they battled an outbreak that at its height was causing 4,000 deaths a day. Doctors associations say that more 1,500 doctors have died from Covid since the pandemic began.

https://twitter.com/haqsmusings/status/1475997402733547521?s=20

The prime minister has got new wheels!

Narendra Modi has added the Mercedes-Maybach S650 armoured vehicle to his convoy of the Range Rover Vogue and Toyota Land Cruiser.

Modi was spotted in the new Maybach 650 armoured car at Hyderabad House while welcoming President Putin of Russia. The vehicle was spotted again in the convoy of Modi recently.

The Mercedes-Maybach S650 Guard offers the highest level of armoured protection available on a car. According to reports, the vehicle can withstand bullets thanks to the upgraded windows and body shell and can take an assault from AK-47 rifles.

As per reported information, the car's windows are coated with polycarbonate and can withstand hardened steel core bullets. The car also boasts of an Explosive Resistant Vehicle (ERV) 2010 rating and the occupants of the vehicle are protected from a 15kg TNT explosion from a distance of only 2 metres.

The cabin also receives a separate air supply in case of a gas attack.

The car is fitted with a 6.0-litre twin-turbo V12 engine that develops 516 bhp and about 900 Nm of peak torque. The top speed is restricted to 160 kmph.

Another report stated that the fuel tank of the Mercedes-Maybach S650 Guard is coated with a special material that seals the holes automatically after a hit. It is made up of the same material that Boeing uses for its AH-64 Apache tank attack helicopters.

The car has a luxurious interior and offers all the comforts that the standard Maybach S-Class can provide.

As the car has been modified for the prime minister, the cost of the vehicle is unknown. However, Mercedes-Maybach launched the S600 Guard in India last year for Rs 10.5 crore and the S650 can cost more than Rs 12 crore.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has had a few cars over the years. As Gujarat chief minister, he had a

bulletproof Mahindra Scorpio. When he became prime minister in 2014, he moved up to the BMW 7 Series High-Security Edition. He then added the Land Rover Range Rover Vogue and the Toyota Land Cruiser.

https://indianexpress.com/article/india/oxfam-report-2021-income-households-fell-7726844/

The income of 84 per cent of households in the country declined in 2021, but at the same time the number of Indian billionaires grew from 102 to 142, an Oxfam report has said, pointing to a stark income divide worsened by the Covid pandemic.

The Oxfam report, “Inequality Kills’’, released on Sunday ahead of the World Economic Forum’s Davos Agenda, also found that as Covid continued to ravage India, the country’s healthcare budget saw a 10% decline from RE (revised estimates) of 2020-21. There was a 6% cut in allocation for education, the Oxfam report says, while the budgetary allocation for social security schemes declined from 1.5% of the total Union budget to 0.6%.

The India supplement of the global report also says that in 2021, the collective wealth of India’s 100 richest people hit a record high of Rs 57.3 lakh crore (USD 775 billion). In the same year, the share of the bottom 50 per cent of the population in national wealth was a mere 6 per cent.

During the pandemic (since March 2020, through to November 30, 2021), the report says, the wealth of Indian billionaires increased from Rs 23.14 lakh crore (USD 313 billion) to Rs 53.16 lakh crore (USD 719 billion). More than 4.6 crore Indians, meanwhile, are estimated to have fallen into extreme poverty in 2020, nearly half of the global new poor according to the United Nations.

https://wir2022.wid.world/www-site/uploads/2021/12/WorldInequalityReport2022_Full_Report.pdf

Ramkrishna referred to the unknown yogi as “Sironmani” [the exalted one] and shared with him information such as NSE’s five year projections, financial data, dividend ratio, business plans, agenda of board meeting, and even consulted him on employee performance appraisals.

Ramkrishna was ousted from NSE in 2016 for her role in the co-location and algo trading scam and abuse of power in the appointment of Subramanian. The probe found that Ramkrishna ran NSE with impunity. No one from the senior management, board, or the promoters — which include big government institutions and banks — ever objected to her ways. Instead, Ramkrishna was given ₹44 crore as pending dues and salary when she left NSE.

SEBI’s probe revealed that Ramkrishna communicated with the yogi, whom she had never met, over email, for almost 20 years and he guided her to appoint Subramanian as the second in command at NSE. “Their spiritual powers do not require them to have any such physical coordinates and would manifest at will,” Ramkrishna told SEBI. The contents of the email were not denied by her.

On January 18, 2013, Subramanian was offered the role of Chief Strategic Advisor at NSE for an annual compensation of ₹1.68 crore against his last drawn salary (as per his claim) of ₹15 lakh at Balmer Lawrie. In March 2014, Ramkrishna approved a 20 per cent increment to Subramanian and his salary was revised to ₹2.01 crore. Five weeks thereafter, Subramanian’s salary was again revised upwards by 15 per cent to ₹2.31 crore as Ramkrishna dubbed his performance to be A+ (exceptional). By 2015, his cost-to-company had zoomed to ₹5 crore, he was given a cabin next to Ramkrishna and granted first-class international air travel. All this was in accordance with the yogi’s instructions.

An email from the unknown yogi even carried the diktat that Subramanian be exempt from the contractual 5-day work week and instead be asked to come only for three days and allowed to work the rest of the time at will.

Another email on September 5, 2015, from the yogi told Ramkrishna, “SOM, if I had the opportunity to be a person on Earth then Kanchan is the perfect fit. Ashirvadhams.” On December 30, 2015, Ramkrishna told the Yogi in her reply, “SIRONMANI, struggle is I have always seen THEE through G, and challenged myself to on my own realise the difference.” ‘SOM’ refers to Ramkrishna, and ‘Kanchan’ and ‘G’ refer to Subramanian, the SEBI probe revealed.

These findings were confirmed by Dinesh Kanabar, the then Chairman of NSE nomination and remuneration committee. Subramanian had all the powers of the MD and CEO, and was flying first class, but remained a consultant on paper. SEBI had observed that there was a glaring conspiracy of a money making scheme involving NSE’s boss with the unknown person.

An email dated February 18, 2015, from Ramkrishna to the unknown yogi, reads, “The role and designation of Group Chief Coordination Officer is fine and we could take that forward. I have a small submission, can we make this as Group President and Chief Coordination Officer? And over a time frame as you direct we can move the entire operations of the exchange under G and redesignate him as Chief Operating Officer? Seek Your guidance on the path forward on this Swami If this meets with your Highness’ approval, then parallelly could we coin JR (Ravi) as Group President Finance and stakeholder relations and Corporate General Counsel?”

Every year, roughly 1.5 million students take the National Eligibility cum Entrance Test, or NEET, to compete for some 90,000 seats in medical schools across India. About half of those are at private universities where tuition and other fees easily exceed $100,000. As a result, tens of thousands of Indian students opt to study medicine in countries like China, Russia, and Ukraine, where education is cheaper.

Opposition to NEET has been brewing since the government introduced the exam in 2013. Critics say that NEET favors students from elite backgrounds who can afford specialized coaching – echoing arguments against the SAT and ACT in the United States – or who can attend expensive private colleges where the bar for admission is lower. “The system is not fair; there cannot be any doubt on that,” says Dr. Anand Krishnan, a professor of community medicine at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences in New Delhi. “Medical profession is not just pure knowledge. You have to be more humane. There are a lot of other characteristics which are important to look for.”

When Mr. Gahlot was in 11th grade, he left his hometown of Siryawali in northwest Uttar Pradesh to go to Kota, Rajasthan, the academic coaching capital of India. There, he says, he followed a grueling regimen of studying six to seven hours a day, but fell about 50 points short of what was required to get into a government-run college.

“It was totally depressing. I would think I’m not smart enough to be a doctor, I can’t do this,” he says. Several of his friends in similar situations chose different career paths. But Mr. Gahlot had made up his mind to become a doctor in eighth grade, and turned to his last resort – going abroad. He says he was too ashamed to tell his peers he was leaving India, because many see foreign medical students as “quitters” who weren’t able to crack NEET.

The fierce competition for Indian medical school seats cost another student his life. Naveen Gyanagoudar had gone outside to buy food when he was killed by Russian shelling in Kharkiv, Ukraine. Speaking to local reporters, his distraught father lamented that despite scoring 97% on high school exams, his son couldn’t get admission to a medical school in his own country.

The double blow of high competition and high cost means India’s new generation of doctors lacks diversity. “They are predominantly urban-centric kids, from well-entrenched, reasonably well-off middle-class families,” says Dr. Sita Naik, a former member of the Medical Council of India, which used to oversee medical education. Dr. Naik says these graduates are unlikely to move to rural areas, where the demand for doctors is the greatest. Rural India is home to two-thirds of the country’s population but only 20% of its doctors, according to a 2016 report.

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-61091336

People belonging to the country's most marginalised social groups - adivasis or indigenous people, Dalits (formerly known as untouchables) and Muslims - are more likely to die at younger ages than higher-caste Hindus, according to one paper by Sangita Vyas, Payal Hathi and Aashish Gupta.

They examined official health survey data of more than 20 million people from nine Indian states accounting for about half of India's population of 1.4 billion.

---------------

Here's the average lifespan of disadvantaged men: 60 years for adivasis, 61.3 for Dalits, and 63.8 for Muslims. An average higher-caste Hindu man is expected to live for 64.9 years.

Such enduring gaps were comparable in terms of years to the gaps in life expectancies between black and white Americans in the US, researchers say. Since life expectancy in India is less than four-fifths the level in the US, the outcomes in India are more substantial in percentage terms.

To be sure, buoyed by advances in medicine, hygiene and public health, India has made massive gains in life expectancy: half a century ago, the average Indian would beat the odds by surviving into his or her 50s. Now they're expected to live almost 20 years longer.

Dalit women are among the most oppressed in the world

The bad news is that although life expectancy for all social groups has increased, disparities have not reduced, according to a related study by Aashish Gupta and Nikkil Sudharsanan.

In some cases, absolute disparities have increased: the life expectancy gap between Dalit men and upper-caste Hindu men, for example, had actually increased between the late 1990s and mid-2010s. And although Muslims had a modest life expectancy disadvantage compared to high castes in 1997-2000, this gap has grown substantially over the past 20 years.

India is home to some of the largest populations of marginalised social groups in the world. The 120 million adivasis - an "invisible and marginal minority", in the words of a historian - live in considerable poverty in some of the remotest parts. Despite political and social empowerment, the 230 million Dalits continue to face discrimination. And an overwhelming majority of 200 million Muslims, the third largest number of any country, continue to languish at the bottom of the social ladder and often become targets of sectarian violence.

What explains these gaps in life expectancy in different groups?

India is neither a melting pot nor a salad bowl

Here is where it gets interesting.

Researchers find that differences in where people live, their wealth and exposure to environment account for less than half of these gaps. For example, the study found that adivasis and Dalits live shorter than higher-caste Hindus across wealth categories.

To find more precise answers on how discrimination influences mortality, India needs to step up research. There is some evidence which tells us why, for example, Muslims live longer than the adivasis and Dalits. They include lower exposure to open defecation among children, lower rates of cervical cancers among women, lower consumption of alcohol and lower incidence of suicide.

https://biz30.timedoctor.com/average-salary-in-pakistan/

The average salary in Pakistan is 81,800 PKR (Pakistani Rupee) per month, or around USD 498 according to the exchange rates in August 2021.

The Pakistan average is significantly lower than the US average (USD 7,900) but comparable to India (USD 430), Ukraine (USD 858), and the Philippines (USD 884). It’s one of the many reasons why Pakistan is a viable alternative to these popular outsourcing destinations.

However, you’ll need a more comprehensive analysis to understand the total expenditure on a Pakistani employee.

In this article, we’ll share vital figures and comparisons related to the average salary in Pakistan. We’ll also explore the country’s payroll rules and top reasons to outsource there.

Average Salary in Pakistan: Key Figures

The average salary figure for a country is the sum of the salaries of the working population divided by the total number of employees. It may also include benefits such as housing, transport allowance, insurance, etc., on top of the employee’s basic salary.

The average salary is usually a good indicator of the typical income of a working citizen in the country.

Here are some key salary figures for Pakistan according to Salary Explorer, a salary comparison website:

The average remuneration in Pakistan may vary between 20,700 PKR per month (average minimum salary) and 365,000 PKR per month (maximum average). Please remember that this is an average salary range, and the actual maximum salary may be higher.

The median salary in Pakistan is 76,900 PKR per month.

If we sort the employee salaries in Pakistan in ascending or descending order, the median represents the central point in the distribution. In other words, half the Pakistani employees earn more than 76,900 PKR per month, while the other half earn less.

These national average salary figures may give you a general estimate and help compare expenditure on employee salaries among different countries.

But it won’t help you determine the exact remuneration for each employee in your company.

For that, you’ll need to consider other factors like

The type of industry.

Years of experience and qualification of the employee.

The kind of work: entry level, professional, etc.

The mode of work: full-time, part-time, remote, etc.

The region where you are operating.

The cost of living in the country.

So let’s take a more comprehensive look at the salary information in Pakistan.

A. Average Salary by Industry

The average salary in a country may vary significantly with the type of industry.

Pakistan is known for its cotton, textile, and agriculture exports, and these industries have a significant share in the country’s GDP. Due to this reason, the manufacturing sector usually employs a large portion of the Pakistani workforce.

Here’s an industry-wise breakdown of the average salaries in Pakistan:

Industry Average Monthly Salary

Energy 73,600 PKR

Information Technology 82,100 PKR

Healthcare 122,000 PKR

Real Estate 92,600 PKR

Media / Broadcasting 75,200 PKR

Telecommunication 72,100 PKR

Source: salaryexplorer.com

B. Average Salary by Region

While the capital city of Islamabad is the administrative center of the country, Karachi and Lahore are the major commercial hubs in Pakistan.

The average employee salary in the country depends on which city you’re operating in.

Here’s the salary report for major Pakistani cities:

City Average Monthly Salary

Karachi 88,300 PKR

Lahore 86,800 PKR

Islamabad 76,400 PKR

Faisalabad 85,400 PKR

Source: salaryexplorer.com

C. Salary Variations by Education

As a general rule of thumb, a Pakistani employee with higher educational degrees gets a higher pay scale than their peers with a lesser degree for the same type of work.

But how does the pay scale change with the education level?

Known for its caste system, India is often thought of as one of the world's most unequal countries. The 2022 World Inequality Report (WIR), headed by leading economist Thomas Piketty and his protégé, Lucas Chancel, did nothing to improve this reputation. Their research showed that the gap between the rich and the poor in India is at a historical high, with the top 10% holding 57% of national income—more than the average of 50% under British colonial rule (1858–1947). In contrast, the bottom half accrued only 13% of national revenue. A February report by Oxfam noted 2021 alone saw 84% of households suffer a loss of income while the number of Indian billionaires grew from 102 to 142.

Both reports highlight not only the problem of revenue inequality but also of opportunity. While there may be disagreement between left and right on the ethics of equality, there is a consensus that everyone should be given the chance to succeed and the principle of fairness—and not factors such as birth, region, race, gender, ethnicity or family backgrounds—ought to lay the foundations of a level playing field for all.

Drawing from the latest pre-pandemic database from the Periodic Labor Force Survey of 2018–19, our research confirms this is far from the case in India. On the one hand, the country has had a consistently high GDP growth rate of more than 7% for nearly two decades, the exception being the period around the 2008 financial crisis. On the other hand, this income has failed to trickle down to India's marginalized communities, with preliminary results pointing to a higher level of inequality of opportunity in the country than in Brazil or Guatemala.

Precarity as well as a large shadow economy also plague the country's labor market. Even before the pandemic, only 30% to 40% of regular salaried adult Indian earners had job contracts or social securities such as national pension schemes, provident fund or health insurance. For self-employed workers, the situation is even more critical, even though these constituted nearly 60% of the Indian labor force in 2019.

Castes, gender and background still determine life chances

Our research indicated that at least 30% of earning inequality is still determined by caste, gender and family backgrounds. The seriousness of this figure becomes clear when it's compared with rates of the world's most egalitarian countries, such as Finland and Norway, where the respective estimates are below 10% for a similar set of social and family attributes.

The caste system is a distinctive feature of Indian inequality. Emerging around 1500 BC, the hereditary social classification draws its origins from occupational hierarchy. Ancient Indian society was thought to be divided in four Varnas or castes: Brahmins (the priests), Khatriyas (the soldiers), Vaishyas (the traders) and Shudras (the servants), in order of hierarchy. Apart from the above four, there were the "untouchables" or Dalits (the oppressed), as they are called now, who were prohibited to come into contact with any of the upper castes. These groups were further subdivided in thousands of sub-castes or Jatis, with complicated internal hierarchy, eventually merged into fewer manageable categories under the British colonization period.

The Indian constitution secures the rights of the Scheduled Castes (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST) and Other Backward Class (OBC) through a caste-based reservation quota, by virtue of which a certain portion of higher-education admissions, public sector jobs, political or legislative representations, are reserved for them. Despite this, there is a notable earning inequality between these social categories and the rest of the population, who consists of no more than 30% to 35% of Indian population. Adopting a data-driven approach we find that, on average, SC, ST and OBC still earn less than the rest.

While unique, the caste system is not the only source of unfairness. Indeed, it accounts for less than 7% of inequality of opportunity, something that's in itself laudable. We will need to add criteria such as gender and family background differences to explain 30% of inequality.

In a country where femicides and rapes regularly make headlines, it comes as no surprise that women from marginalized social groups are often subject to a "double disadvantage." For some states such as Rajasthan (in the country's northwest), Andhra Pradesh (south), Maharashtra (center), we find even upper-caste women enjoy fewer educational opportunities than men from the marginalized SC/ST communities. Even among the graduates, while the national average employment rate for males is 70%, it is below 30% for the females.

A temporary byproduct of rising growth?

Rising inequality could be dismissed as a temporary byproduct of rapid growth on the grounds of Simon Kuznets' famous hypothesis, according to which inequality rises with rapid growth before eventually subsiding. However, there is no guarantee of this, least of all because widening gap between rich and poor is not only limited to fast-growing countries such as India. Indeed, a 2019 study found that the growth-inequality relationship often reflects inequality of opportunity and prospects of growth are relatively dim for economies with a bumpy distribution of opportunities.

Despite sporadic evidence of converging caste or gender gaps, our research shows an intricate web of social hierarchy has been cast over every aspect of life in India. It is true that some deprived castes may withdraw from school early to explore traditional jobs available to their caste-based networks—thereby limiting their opportunities. However, are they responsible for such choices or it is the precariousness of the Indian economy that pushes them down such routes? There is no straightforward answer to these questions, even if some of the "bad choices" that individuals make can result more from pressure than choice.

Given the complicated intertwining of various forms of hierarchy in India, broad policies targeting inequality may have less success than anticipated. Dozens of factors other than caste, gender or family background feed into inequality, including home sanitation, school facilities, domestic violence, access to basic infrastructure such as electricity, water or healthcare, crime rates, political stability of the locality, environmental risks and many more.

Better data would allow researchers studying India to capture the contours of its society and also help gauge the effectiveness of policies intended to expand opportunities for the neediest.

https://www.india.com/business/23-cr-people-with-income-less-than-rs-375-day-rss-gen-secy-raises-poverty-unemployment-alarm-5665302/

He also spoke about the rising levels of economic inequality that the country is witnessing today. Acknowledging that India is among the top six economies of the world, he said top 1 per cent holds 1/5th (20 per cent) of the nation’s income. He added that 50 per cent of the country’s population has only 13 per cent of the country’s income. Hosabale went on to quote United Nations’ observations on the poverty and development in India. Also Read - Today Will be Your Last Working Day With Uber: Ride-hailing Firm Lays Off Nearly 3,700 Employees Via Zoom

“A large part of the country still does not have access to clean water and nutritious food. Civil strife and the poor level of education are also a reason for poverty. That is why a New Education Policy has been ushered in. Even climate change is a reason for poverty. And at places the inefficiency of the government is a reason for poverty.”

In his speech, Hosabale also stressed on the importance of creating an entrepreneurship-friendly environment apart from the need to carry skill-training from the urban to rural India.

“During Covid, we learnt that there is a possibility of generating jobs at the rural level according to local needs and using local talent. That is why the Swavalambi Bharat Abhiyan was launched. We don’t just need all-India level schemes, but also local schemes. It can be done in the field of agriculture, skill development, marketing etc. We can revive cottage industry. Similarly, in the field of medicine, a lot of Ayurvedic medicines can be manufactured at the local level. We need to find people interested in self-employment and entrepreneurship,” Hosabale said.

Hannah Ellis-Petersen in Delhi

Mon 14 Nov 2022 01.30 EST

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/nov/14/india-faces-deepening-demographic-divide-as-it-prepares-to-overtake-china-as-the-worlds-most-populous-country

The cry of a baby born in India one day next year will herald a watershed moment for the country, when the scales tip and India overtakes China as the world’s most populous nation.

Yet the story of India’s population boom is really two stories. In the north, led by just two states, the population is still rising. In the richer south, numbers are stabilising and in some areas declining. The deepening divisions between these regions mean the government must eventually grapple with a unique problem: the consequences of a baby boom and an ageing population, all inside one nation.

India is currently home to more than 1.39 billion people – four times that of the US and more than 20 times the UK – while 1.41bn live in China. But with 86,000 babies born in India every day, and 49,400 in China, India is on course to take the lead in 2023 and hit 1.65 billion people by 2060.

On 15 November the world’s population will reach a total of 8 billion people. Between now and 2050, over half of the projected increase in the global population will happen in just eight countries: the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Egypt, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Pakistan, the Philippines, the United Republic of Tanzania – and India.

The growth will place huge pressure on India’s resources, economic stability and society, and the repercussions will reach far beyond its borders. As a country on the forefront of the climate crisis, already grappling with extreme weather events 80% of the year, diminishing resources such as water could become decisive factors in what India’s future population looks like.

One country, two stories

Fears of “population explosion” in India – where development caves in beneath the weight of an uncontrollably expanding population and the country’s resources are overrun, leaving millions to starve – have abounded for over a century.

Post independence, India’s population grew at a significant pace; between 1947 and 1997, it went from 350 million to 1 billion. But since the 1980s, various initiatives worked to convince families, particularly those from poorer and marginalised backgrounds who tend to have the most children, of the benefits of family planning. As a result, India’s fertility rate began to fall faster than any of the doomsday “explosion” scenarios had predicted.

A small family is now the norm in India, and with the annual population growth rate less than 1%, fears of population-driven collapse are no longer seen as realistic. In the 1950s, a woman in India would give birth to an average of over six children; today the national average is just over two and still continuing to fall.

Nonetheless, the curbs on population growth have not been uniform across India, and India’s entrenched north-south divide has played out significantly in demographics, with ongoing social and political consequences.

For the next decade, one-third of India’s population increase will come from just two northern states, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. Bihar, the only state in India where women still typically have more than three children, is not expected to hit population stability – 2.1 children per woman – until 2039. Kerala, India’s most educated, progressive state, hit that figure in 1998.

Hannah Ellis-Petersen in Delhi

Mon 14 Nov 2022 01.30 EST

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/nov/14/india-faces-deepening-demographic-divide-as-it-prepares-to-overtake-china-as-the-worlds-most-populous-country

In Bihar’s poverty stricken area of Kishanganj, which has one of the highest rates of fertility in India, women said they had only recently begun to learn about the benefits of a having fewer children.

The urge to have sons, who in parts of India are still considered much more desirable than daughters, remained a key motivator for women in the village. Surta Devi, 36, said she had six children in order to make sure she had two sons to “carry on our lineage”.

“It was only after I gave birth to all my children that doctors told me about family planning,” said Devi.

Phullo Devi, 55, an illiterate labourer who had six children before she opted for sterilisation, said she wished she had done things differently. “If I had less children, I would have been able to raise them better and been able to educate them,” she said.

But Devi said things were slowly changing in the village. “Now health workers campaign house-to-house and make people aware about contraception and condoms. I absolutely want my sons and daughters to have less children so they don’t have to live in poverty,” she said.

The ‘youth bulge’

A particular demographic challenge, widespread across India but particularly concentrated in poorer northern states, is that of the “youth bulge”. The median age of an Indian is 29 and the country is grappling with a vast, ambitious and increasingly restless young population, the majority of whom are unskilled, and for whom there are not enough schools, universities, training programmes and most of all, not enough jobs. Across India, youth unemployment is 23% and only one in four graduates are employed. While female literacy is growing, only 25% of women in India participate in the workforce.

Advertisement

In Uttar Pradesh, where the median age is 20, there are over 3.4 million unemployed young people. Earlier this year, riots broke out in Bihar after more than twelve million people applied for 35,000 positions in the Indian Railways.

Vishu Yadav, 25, from Ghazipur district in Uttar Pradesh, has a masters degree, an education diploma and passed a teacher eligibility test, but is unemployed, with teaching jobs scarce and over a million people now applying for officer positions in the state civil service. “It’s a depressing, hopeless situation. I am eligible to become a teacher but I can not secure a position. There are too many young people with qualifications and not enough jobs,” he said.

Poonam Muttreja, the executive director of Population Foundation India, said there was still time for this young population to work to India’s benefit.

“India has a fantastic window of opportunity but it will only be there for approximately the next two decades,” said Muttreja. “We have the capacity to tap into the potential of the youth population but we need to invest in adolescent education, health and sexual health right away if we want to reap the benefits.

“Otherwise, our demographic dividend could turn into a demographic disaster.”

Muttreja said India’s youth risk fuelling population growth unless contraception and family planning services are improved, describing the situation as “woefully inadequate”.

Female sterilisation is still the most widely used contraceptive method in India, and that’s mostly by older married women. Of India’s tiny health budget, only 6% is put aside for family planning, and just 0.4% of that is invested in temporary methods such as the contraceptive pill or condoms.

“Currently we have almost 360 million young people, the majority of whom are at a reproductive age, and that number is only going to increase over the next few decades,” Muttreja said.

Analysis by Andy Mukherjee | Bloomberg

https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/the-squeeze-onindias-spenders-is-yetto-lift/2023/01/22/064843c8-9aa3-11ed-93e0-38551e88239c_story.html

Manufacturing of wants is hard anywhere for marketers, but the challenge is bigger when the bottom half of the population takes home only 13% of national income. While India’s rapid economic growth since the 1990s has undoubtedly expanded the spending capacity of its 1.4 billion people, acute and rising inequality — among the worst in the world — makes for a notoriously budget-conscious median consumer. Companies can take nothing for granted: For Unilever’s local Indian unit, a late winter crimped sales of skin-care products last quarter.

Still, the maker of Dove body wash and Surf detergent managed to eke out an overall 5% increase in sales volume from a year earlier, lifting net income to 25.1 billion rupees ($309 million), slightly better than expected. That was achieved by price cuts — passing along the benefit of lower palm-oil costs to soap buyers — and a step up in promotion and advertising. Still, not all players have the market leader’s financial chops. Investors who look closely at Hindustan Unilever Ltd.’s earnings for a pulse on India’s consumer demand will note with dismay the slide in industry-wide volumes for cleaning liquids, personal care items and food, the categories in which the firm competes.

This isn’t new. Consumer demand in India has been moderating since August 2021. Village households, many of which had to liquidate their gold holdings and other assets to treat Covid-19 patients during that summer’s lethal delta outbreak, were not in a mood to spend even after the surge in deaths and hospitalization ebbed.

Then, as major economies began to open up and crude oil and other commodities began to get pricier, firms like Unilever responded to the squeeze by reducing how much they put in a pack. Their idea was to hold on to psychologically crucial “magic price points” — such as five or 10 rupees — in the hope that customers will replenish more often. But when inflation accelerated after the start of the war in Ukraine, there was no option except to shatter the illusion of affordability by raising prices. Volumes flat-lined in the March quarter.

“The worst of inflation is behind us,” Sanjiv Mehta, the chief executive officer, said in a statement after last week’s earnings report. That seems to be the case indeed. India’s aggregate price index rose a slower-than-expected 5.7% in December, the third straight month of cooling. That’s why perhaps instead of pushing four 100-gram bars of Lux soap for 140 rupees, Unilever is charging 156 rupees for five, according to the Business Standard. In offering an 11% price cut by bulking up pack sizes, the company is betting that most households’ budget can now accommodate an extra outlay of 16 rupees.

It’s a reasonable gamble. A bumper wheat harvest is expected this spring. Rural India, which employs two out of three workers, found jobs for a disproportionately larger share of new entrants to the labor force in November and December, according to Mahesh Vyas of CMIE, a private firm that fills in for reliable official jobs data. “Most of the additional employment is happening in rural India and not in the towns,” he says.

And that may well put the spotlight next year on faltering spending in cities. The tech industry is wobbling globally. In India, too, startups are firing employees in large numbers; some former darlings of venture capital, such as online test-prep and education firms, are becoming irrelevant now that Covid-19 restrictions on physical classes have ended.

Meanwhile, India’s software-exports industry — a large employer in metropolises — has become wary of hiring because of slowing global growth. “The pain in urban consumption seems to be showing up,” JM Financial analysts Richard Liu and others wrote last week after Asian Paints Ltd.’s earnings.

Ashoka Mody, who was for many years a senior economist at the International Monetary Fund, is the sort of quietly efficient global technocrat who retires to a professorship at a prestigious school—in his case, Princeton. Yet he’s different from his faceless ilk of briefcase-bearers in one astonishing way: 13 years ago, an attempt was made on his life. The alleged assailant, thought to have been passed over for a job at the IMF by Mr. Mody, shot him in the jaw outside his house in Maryland.

He recovered with remarkable verve, his intellectual drive intact. Yet a mood of gloom and pessimism is unmistakable in “India Is Broken.” Today, 75 years after independence from Britain, Mr. Mody believes that India’s democracy and economy are in a state of profound malfunction. The book’s tale, he writes, “is one of continuous erosion of social norms and decay of political accountability.” You might add that it is also a tale of an audacious political experiment on the brink of failure.

India started its post-independence journey, says Mr. Mody, as “an improbable democracy” whose citizens, mostly illiterate and poor, hungered for freedom and prosperity. Generations of Indian politicians—from Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister, to Narendra Modi, the present one—have “betrayed the economic aspirations” of millions. India’s democracy no longer protects fundamental rights and freedoms in a nation over which “a blanket of violence” has fallen. A belief in “equality, tolerance and shared progress” has disappeared. And the country’s collapse isn’t just political and economic; it’s also moral and spiritual.

------------

A notable weakness in Mr. Mody’s analysis is his denial that the economic policies of Nehru and his successors were socialist. He writes of Nehru’s “alleged socialist legacy” and adds that it is a “mistake to identify central planning or big government as socialism.” Socialism, he insists, “means the creation of equal opportunity for all,” which India’s policy makers weren’t doing. Ergo, India wasn’t socialist.

If these protestations are almost laughable, Mr. Mody’s solution also invites some derision. Hope for India, he says, lies in making it a “true democracy.” And how can that be done? “We must move to an equilibrium in which everyone expects others to be honest.” This “honest equilibrium,” he says, will promote enough trust for Indians to work together “in the long-haul tasks of creating public goods and advancing sustainable development” and awakening “civic consciousness.” Mr. Mody, it is clear, has a dream. It is naïve, and it is corny. India, alas, will continue to be “broken” for many years to come.

https://international.princeton.edu/news/why-prof-ashoka-mody-believes-india-broken

I have long felt that that upbeat story is completely divorced from the lived reality of the vast majority of Indians. I wanted to write a book about that lived reality, about jobs, education, healthcare, the cities Indians live in, the justice system they encounter, the air they breathe, the water they drink. And when you look at India through that lens of that reality, the progress is halting at best and far removed from the aspirations of people and what might have been. India is broken in the sense that for hundreds of millions of Indians, jobs are hard to get, and education and health care are poor. The justice system is coercive and brutal. The air quality remains extraordinarily poor. The rivers are dying. And it's not clear that things are going to get better. Underlying that brokenness, social norms and public accountability have eroded to a point where India seems to be in a catch-22: Unaccountable politicians do not impose accountability on themselves; therefore, no one has an incentive to impose accountability for policy priorities that might benefit large numbers of people. The elite are happy in their gated first-world communities. They shrug their shoulders and say, “What exactly is the problem?”

———

Prof Ashoka Mody interviewed by Barkha Dutt

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L8SEmML71KQ

Bangladesh 54%

Pakistan 54%

India 74%

https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.EMP.VULN.ZS?locations=PK-IN-BD

------------

Sandeep Manudhane

@sandeep_PT

Why the size of the economy means little

a simple analysis

1) We are often told that India is now a $3.5 trillion economy. It is growing fast too. Hence, we must be happy with this growth in size as it is the most visible sign of right direction. This is the Quantity is Good argument.

2) We are told that such growth can happen only if policies are right, and all engines of the GDP - consumption, exports, investment, govt. consumption - are doing their job well. We tend to believe it.

3) We are also told that unless GDP grows, how can Indians (on average) grow? Proof is given to us in the form of 'rising per capita incomes' of India. And we celebrate "India racing past the UK" in GDP terms, ignoring that the average Indian today is 20 times poorer than the average Britisher.

4) All this reasoning sounds sensible, logical, credible, and utterly worth reiterating. So we tend to think - good, GDP size on the whole matters the most.

5) Wrong. This is not how it works in real life.

6) It is wrong due to three major reasons

(a) Distribution effect

(b) Concentration of power effect

(c) Inter-generational wealth and income effect

7) First comes the distribution effect. Since 1991, the indisputable fact recorded by economists is that "rich have gotten richer, and poor steadily stagnant or poorer". Thomas Piketty recorded it so well he's almost never spoken in New India now! Thus, we have a super-rich tiny elite of 2-3% at the top, and a vast ocean of stagnant-income 70-80% down below. And this is not changing at all. Do not be fooled by rising nominal per capita figures - factor in inflation and boom! And remember - per capita is an average figure, and it conceals the concentration.

8) Second is the Concentration of power effect. RBI ex-deputy governor Viral Acharya wrote that just 5 big industrial groups - Tata, Birlas, Adanis, Ambanis, Mittals - now disproportionately own the economic assets of India, and directly contribute to inflation dynamics (via their pricing power). This concentration is rising dangerously each year for some time now, and all government policies are designed to push it even higher. Hence, a rising GDP size means they corner more and more and more of the incremental annual output. The per capita rises, but somehow magically people don't experience it in 'steadily improving lives'.

9) Third is the Inter-generational wealth and income effect. Ever wondered why more than 90% of India is working in unstructured, informal jobs, with near-zero social security? Ever wondered why rich families smoothly pass on 100% of their assets across generations while paying zero taxes? Ever wondered how taxes paid by the rich as a per cent of their incomes are not as high as those paid by you and me (normal citizens)? India has no inheritance tax, but has a hugely corporate-friendly tax regime with many policies tailor-made to augment their wealth. Trickle down is impossible in this system. But that was the spiel sold to us in 1991, and later, each year! There is no incentive for giant corporates (and rich folks) to generate more formal jobs, as an ocean of underpaid slaves is ready to slog their entire lives for them. Add to that automation, and now, AI systems!

SUMMARY

Sadly, as India's GDP grows in size, it means little for the masses because trickle-down is near zero. That is because new formal jobs aren't being generated at scale at all (which in itself is a big topic for analysis).

So, our Quantity of GDP is different from Quality of GDP.

https://twitter.com/sandeep_PT/status/1675421203152896001?s=20

https://indianexpress.com/article/india/income-of-poorest-fifth-plunged-53-in-5-yrs-those-at-top-surged-7738426/

In a trend unprecedented since economic liberalisation, the annual income of the poorest 20% of Indian households, constantly rising since 1995, plunged 53% in the pandemic year 2020-21 from their levels in 2015-16. In the same five-year period, the richest 20% saw their annual household income grow 39% reflecting the sharp contrast Covid’s economic impact has had on the bottom of the pyramid and the top.

---------------

A new survey, which highlights the economic impact of the pandemic on Indian households, found that the income of the poorest 20 percent of the country declined by 53 percent in 2020-21 from that in 2015-16.

https://www.thequint.com/news/india/poor-in-india-lose-half-their-income-in-last-5-years-rich-got-richer-survey#read-more

The survey, conducted by the People's Research on India's Consumer Economy (PRICE), a Mumbai-based think tank, also shows that in contrast, the same period saw the annual household income of the richest 20 percent grow by 39 percent.

Conducted between April and October 2021, the survey covered 20,000 households in the first stage, and 42,000 households in the second stage. It spanned over 120 towns and 800 villages in 100 districts.

Income Erosion in All Households Except the Rich Ones

The survey indicated that while the poorest 20 percent households witnessed an income erosion of 53 percent, the lower-middle-class saw a 39-percent decline in household income. The income of the middle-class, meanwhile, reduced by 9 percent.

However, the upper-middle-class and richest households saw their incomes rise by 7 percent and 39 percent, respectively.

The survey also showed that the richest households, on an average, accumulated more income per household as well as pooled income in the past five years than any other five-year period since liberalisation.

While the richest 20 percent accounted for 50.2 percent of the total household income in 1995, the survey shows that their share jumped to 56.3 percent in 2021. In contrast, the share of the poorest 20 percent dropped from 5.9 percent to 3.3 percent in the same period.

While 90 percent of the poorest 20 percent in 2016 lived in rural India, the figure dropped to 70 percent in 2021. In urban areas as well, the share of the poorest 20 percent households went from 10 percent in 2016 to 30 percent in 2021.

"The data reflects that casual labourers, petty traders, household workers, among others, in Tier 1 and Tier 2 cities got hit the most by the pandemic. During the survey, we also noticed that while in rural areas, people in the lower middle income category (Q2) moved to the middle income category (Q3), in the urban areas, the shift has been downwards, from Q3 to Q2. In fact, the rise in poverty level of the urban poor has pulled down the household income of the entire category," reported The Indian Express, quoting Rajesh Shukla, MD and CEO of PRICE.

Most Middle-Class Breadwinners Are Illiterate or Have Primary Schooling

The survey further shows that while a majority of the breadwinners in 'Rich India' (top 20 percent) have completed high-school education (60 percent, of which 40 percent are graduates and above), nearly half of 'Middle India' (60 percent) only have primary education.

As for the bottom 20 percent, 86 percent are either illiterate or just have primary education. Only 6 percent are graduates and above.

(With inputs from The Indian Express, ICE360 2021 Survey.)

(At The Quint, we are answerable only to our audience. Play an active role in shaping our journalism by becoming a member. Because the truth is worth it.)

https://www.business-standard.com/india-news/inequality-surges-in-india-upper-castes-hold-90-of-billionaire-wealth-124062700343_1.html

A recent report from World Inequality Lab titled, ‘Towards Tax Justice and Wealth Redistribution in India’, has laid bare the stark economic disparities that plague India. The findings are sobering: nearly 90 per cent of the country’s billionaire wealth is concentrated in the hands of the upper castes, highlighting a deep socio-economic divide.

Billionaire wealth dominated by upper castes

The analysis in the report unveils a staggering 88.4 per cent of India’s billionaire wealth is controlled by upper castes. In contrast, while Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) together form a significant part of India’s workforce, their representation among enterprise owners remains disproportionately low.

This discrepancy is not limited to the billionaires; the All-India Debt and Investment Survey (AIDIS) for 2018-19 indicates that upper castes hold nearly 55 per cent of the national wealth. This concentration of wealth also highlights the persistent economic inequalities rooted in India’s caste system.

Caste influences financial demographics

Caste continues to play a critical role in determining access to essential resources such as education, healthcare, social networks, and credit — all crucial for entrepreneurship and wealth creation. Historically, Dalits faced prohibitions on land ownership in many regions, severely curtailing their economic progress.

This disparity extends beyond billionaire rankings. The ‘State of Working India, 2023’ report from Azim Premji University further highlights these disparities, showing SCs and STs are underrepresented among enterprise owners relative to their workforce participation. SCs, comprising 19.3 per cent of the workforce, account for only 11.4 per cent of enterprise owners. Similarly, STs, making up 10.1 per cent of the workforce, represent just 5.4 per cent of enterprise owners.

------------

India’s Income Inequality Worse Than Under British Rule: Report | TIME

https://time.com/6961171/india-british-rule-income-inequality/