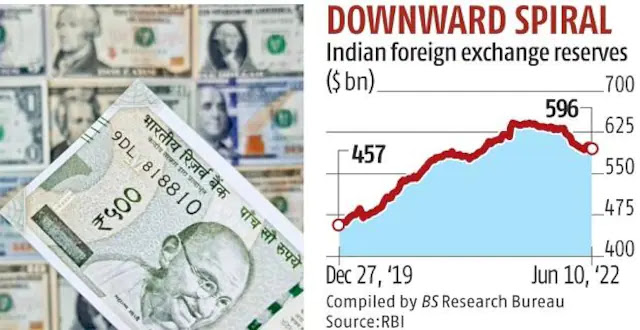

India's Forex Reserves Fall As Foreign Investors Head For The Exits

India's foreign exchange reserves are falling rapidly as foreign investors flee and the country's trade and current account deficits widen. More than $267 billion worth of India's external debt of the total $621 billion is due for repayment in the next nine months. This repayment is equivalent to about 44% of India's foreign exchange reserves. This combination of investors' exodus, widening twin deficits and short-term debt repayments has caused the Indian rupee to hit new lows. Unlike China and other nations that have accumulated large reserves by running trade surpluses, India runs perennial trade and current account deficits. The top contributor to India's forex reserves is debt which accounts for 48%. Portfolio equity investments known as “hot” money or speculative money flows account for 23% of India's forex reserves, according to an analysis published by The Hindu BusinessLine.

|

| India's Declining Forex Reserves. Source: Business Standard |

Investor Exodus:

Foreign portfolio investors have pulled out a whopping $33.5 billion from equity and $2.1 billion from debt segments of Indian financial markets, for a total net outflow of $35.6 billion from October 2021 to June 2022, according to data compiled by the National Securities Depository Limited. In the first half of this calendar year, the total net outflows were $29.7 billion.

It's not just the FPIs leaving India; a number of multinational companies are also pulling foreign direct investment (FDI) from India. Several big names including German retailer Metro AG, Swiss building-materials firm Holcim, US automaker Ford, UK banking major Royal Bank of Scotland, US motorcycle manufacturer Harley-Davidson and US banking behemoth Citibank have chosen to pull the plug on their operations in India or downsize their presence in recent years.

Widening Deficits:

India's finance ministry has warned of a growing twin deficit problem, with higher commodity prices and rising subsidy burden leading to an increase in both the fiscal and current account deficits. India's June trade deficit widened to a record high of $25.63 billion, mainly due to a rise in crude oil and coal imports, from $9.61 billion a year earlier. India's April-May fiscal deficit was $25.8 billion.

Summary:

India's current level of forex reserves is enough for less than 10 months of imports projected for 2022-23. But the country has had a structural current account deficit which has been funded by large capital inflows. The accumulation of forex reserves has been due to surplus in the capital account. Since late February, the foreign exchange reserves have declined by $36 billion. India still has large forex reserves but its economy is in the same boat as other emerging markets that run large and worsening trade and current account deficits. With declining forex reserves, India is likely to face headwinds as the US Federal Reserves raises interest rates to fight inflation.

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

South Asia Investor Review

India in Crisis: Unemployment and Hunger Persist After COVID waves

Food in Pakistan 2nd Cheapest in the World

Western Money Keeps Indian Economy Afloat

Pakistan to Become World's 6th Largest Cement Producer by 2030

How Has India Accumulated Large Forex Reserves Despite Perennial Trade Deficits?

Pakistan's Computer Services Exports Jump 26% Amid COVID19 Lockdown

Coronavirus, Lives and Livelihoods in Pakistan

Vast Majority of Pakistanis Support Imran Khan's Handling of Covid19 Crisis

Pakistani-American Woman Featured in Netflix Documentary "Pandemic"

Incomes of Poorest Pakistanis Growing Faster Than Their Richest Counterparts

Can Pakistan Effectively Respond to Coronavirus Outbreak?

How Grim is Pakistan's Social Sector Progress?

Pakistan Fares Marginally Better Than India On Disease Burdens

Trump Picks Muslim-American to Lead Vaccine Effort

Democracy vs Dictatorship in Pakistan

Pakistan Child Health Indicators

Pakistan's Balance of Payments Crisis

Panama Leaks in Pakistan

Conspiracy Theories About Pakistan Elections"

PTI Triumphs Over Corrupt Dynastic Political Parties

Strikingly Similar Narratives of Donald Trump and Nawaz Sharif

Nawaz Sharif's Report Card

Riaz Haq's Youtube Channel

Comments

For 10 countries, the estimated net outflow of migrants exceeded 1 million over the period from

2010 through 2021. In many of these countries, the outflows were due to temporary labour

movements, such as for Pakistan (net flow of -16.5 million), India (-3.5 million), Bangladesh

(-2.9 million), Nepal (-1.6 million) and Sri Lanka (-1.0 million). In other countries, including

Syrian Arab Republic (-4.6 million), Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic of) (-4.8 million) and

Myanmar (-1.0 million), insecurity and conflict drove the outflow of migrants over this period.

• All countries, whether experiencing net inflows or outflows of migrants, should take steps to

facilitate orderly, safe, regular and responsible migration, in accordance with SDG target 10.7.

------------------

Between 2010 and 2021, 40 countries or areas have experienced a net inflow of more than

200,000 migrants; in 17 of those, the total net inflow exceeded 1 million people.

In 2020, Türkiye hosted the largest number of refugees and asylum seekers worldwide (nearly 4 million),

followed by Jordan (3 million), the State of Palestine (2 million) and Colombia (1.8 million). Other major

destination countries of refugees, asylum seekers or other persons displaced abroad were Germany,

Lebanon, Pakistan, Sudan, Uganda and the United States of America (United Nations, 2020b).

A delegation from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) is set to arrive in Dhaka tomorrow on a nine-day trip to discuss the government's request for a $4.5 billion loan in the form of budgetary support.

Rahul Anand, division chief in the IMF's Asia and Pacific Department, will lead the team during talks with the senior officials of the finance ministry, the central bank, the National Board of Revenue and the Economic Relations Division.

If everything proceeds smoothly, the loan deal could be finalised by October this year, said an official of the finance ministry yesterday.

The request for budgetary support comes to shore up the precarious foreign currency reserves, which yesterday stood at $39.8 billion -- the lowest since October 14, 2020.

This is enough to cover about five months' import bills.

Typically, the World Bank and the IMF prescribe an import cover of three months, but in times of economic uncertainty, they advise keeping sufficient reserves to meet 8-9 months' imports.

Going forward, even though imports are slowly contracting, the elevated inflation levels around the world mean the odds of a slowdown in both remittance inflows and export orders, two sources of foreign currency for Bangladesh, are high.

The IMF officials will look into the impacts of the Russia-Ukraine war and escalated global commodity prices on the Bangladesh economy, the status of recovery from the global coronavirus pandemic and the government's large subsidy programme.

They will see whether the subsidy spending is justified and compare it with the other countries. If it is deemed excessive, the IMF mission may suggest ways to trim it.

Subsidy spending in the just-concluded fiscal year is Tk 66,825 crore, 24.1 percent more than the original allocation thanks to the spiral in fuel and fertiliser prices in the global market.

In this fiscal year's budget, Tk 82,745 crore has been earmarked for subsidy.

But considering the price trend of oil, gas, and fertiliser in the international market, the estimated spending can be 15-20 per cent higher than the initial estimates, said Finance Minister AHM Mustafa Kamal in his budget speech in June.

The Washington-based multilateral lender could tie in conditions for the loan package.

The conditions could include measures to increase revenue, lower subsidy expenditure, market-based exchange rate and lending rate, and reforms in the banking sector and tax administration, the finance ministry official said.

The government has already moved to tighten its belts though.

It has unveiled a relatively smaller budget for the current fiscal year, put on hold low-priority projects, suspended foreign tours of government officials, adjusted the prices of gas and diesel to some extent, and loosened the exchange rate policy.

The government has also signalled that it may raise the price of fuel oil and has proposed to the Bangladesh Energy Regulatory Commission to increase the electricity tariff to cut the subsidy burden.

Surjit Bhalla, executive director of the IMF for India, Bangladesh, Bhutan and Sri Lanka, who represented Bangladesh on the board of the Washington-based lender, is also set to visit Bangladesh separately.

BY HUSAIN HAQQANI AND APARNA PANDE

Some $100 million in assets of Amway, the American multi-level marketing company that sells health, beauty and home care products, have been frozen by Indian law enforcement while the company is investigated for ostensibly “operating a pyramid scheme.” Ironically, the company has done business in India for three decades with the same business model of direct selling.

Moreover, Ricard is not the only international business facing taxation challenges in India. IBM has had $865 million stuck in an escrow account since 2009 while a tax dispute over retroactive tax meanders through India’s legal system. India could have used IBM’s nearly $1 billion if put to productive use.

Two U.K.-based companies – Telecom giant Vodafone and energy company Cairn –were hit with large capital gains tax demands based on legal changes after mergers or acquisitions. The Indian government took one decade to rollback its retroactive taxation policy, only after India lost two cases at the World Bank’s International Center for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) and The Hague tribunal.

The challenges notwithstanding, India’s large size and location continue to make it a prized market for foreign businesses. Air India, the formerly state-run airline now owned by Tata Group, announced plans to overhaul its entire fleet of 300 narrow-body jets in one of the largest orders in commercial aviation history. Boeing and Airbus are the leading contenders for this deal. Access to the large Indian consumer market is a dream, as is the hope for a stake in the upgradation of India’s civilian and military infrastructure.

But, by and large, Western hopes of a modern, fast-growing, prosperous and free market-oriented India have not been realized at the pace predicted by some in the first few years of the 21st century. India’s current rate of economic growth is woefully inadequate for India’s domestic goals as well as the objective of becoming a serious rival to global economic juggernaut, China. The latter makes India’s economic policies a strategic concern for U.S. policymakers.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-07-15/why-india-s-world-beating-growth-isn-t-creating-jobs-quicktake#xj4y7vzkg

No other major economy has been expanding as fast as India lately, beating both China and the US. But beyond the headlines lies the grim reality of rising unemployment. The nation of 1.4 billion people isn’t creating enough jobs for its growing workforce, despite campaign promises by Prime Minister Narendra Modi to make it a priority. Output is increasing as a result of pandemic-related government spending while the private sector sits on the fence, deterred by dim conditions for new investment. Meanwhile, pandemic-related disruptions and rising inflation are making it harder for everyone to get by. Tensions boiled over in June when angry youth facing bleak job prospects blocked rail traffic and highways in many states for days, even setting some trains on fire.

The unemployment rate in India has been hovering around 7% or 8%, up from about 5% five years ago, according to the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, a private research firm. At the same time, the workforce shrank as millions of people dejected over weak job prospects pulled out, a situation that was exacerbated by Covid-19 lockdowns. The labor force participation rate -- meaning people who are working or looking for work -- has dropped to just 40% of the 900 million Indians of legal age, from 46% six years ago, according to the CMIE. By comparison, the participation rate in the US was 62.2% in June.

India gdp growth rate for 2021 was 8.95%, a 15.54% increase from 2020.

India gdp growth rate for 2020 was -6.60%, a 10.33% decline from 2019.

India gdp growth rate for 2019 was 3.74%, a 2.72% decline from 2018.

India gdp growth rate for 2018 was 6.45%, a 0.34% decline from 2017.

https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/IND/india/gdp-growth-rate

--------

Annual percentage growth rate of GDP at market prices based on constant local currency. Aggregates are based on constant 2010 U.S. dollars. GDP is the sum of gross value added by all resident producers in the economy plus any product taxes and minus any subsidies not included in the value of the products. It is calculated without making deductions for depreciation of fabricated assets or for depletion and degradation of natural resources.

Pakistan gdp growth rate for 2021 was 6.03%, a 7.36% increase from 2020.

Pakistan gdp growth rate for 2020 was -1.33%, a 3.83% decline from 2019.

Pakistan gdp growth rate for 2019 was 2.50%, a 3.65% decline from 2018.

Pakistan gdp growth rate for 2018 was 6.15%, a 1.72% increase from 2017.

https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/PAK/pakistan/gdp-growth-rate

https://newsroompost.com/business/indias-current-account-deficit-expected-to-deteriorate-in-fy23-finance-ministry-report/5138583.html

The widening of current account deficit has depreciated the Indian rupee against the US dollar by 6 per cent since January of 2022, and is on the brink of touching 80 mark.

New Delhi India’s current account deficit, meaning a shortfall between the imports and exports, is expected to deteriorate in 2022-23 if recession concerns do not lead to a sustained and meaningful reduction in the prices of food and energy commodities, the Ministry of Finance said in its latest Monthly Economic Review report.

Softening of global commodity prices may put a leash on inflation, but their elevated levels also need to decline quickly to reduce India’s current account deficit.

A sudden and sharp surge in gold imports amid wedding season, as many weddings were postponed to 2022 from 2021 due to pandemic-induced restrictions, is also now exerting pressure on the trade deficit, it said.

The country’s trade deficit widened to USD 45.18 billion in April-June 2022 period as compared to USD 5.61 billion recorded in the corresponding period of last year.

In order to alleviate the impact, the government recently hiked the customs duty on gold from present 10.75 per cent to 15.0 per cent.

“The deterioration of current account deficit could, however, moderate with an increase in service exports in which India is more globally competitive as compared to merchandise exports,” it said.

The widening of current account deficit has depreciated the Indian rupee against the US dollar by 6 per cent since January of 2022, and is on the brink of touching 80 mark.

“The depreciation (in rupee), in addition to elevated global commodity prices, has also made price-inelastic imports costlier, thereby making it further difficult to reduce the CAD,” it said.

A depreciation in rupee typically makes imported items costlier. India’s forex reserves, in the six months since January 2022, have declined by USD 34 billion.

However, the momentum in the Indian economy is holding up better than expected, despite commodity price shocks in the last four months, the report added.

“After a sluggish start, the seasonal rainfall has picked up and it is geographically well dispersed. That is good news too.”

The Indian rupee touched the weakest level on record against the dollar on Tuesday, another victim of higher energy prices and a stronger greenback.

The rupee has lost about 7 percent of its value against the dollar this year as India has spent more to import sources of energy like crude oil, natural gas and coal. Prices of those commodities have climbed after Russia invaded Ukraine.

Another factor behind the decline of the rupee is uncertainty about the global economy that has, in turn, propelled the dollar to a 20-year high against the currencies of its major trading partners. Investors have pulled money out of India and other developing countries and poured it in to the United States, where the Federal Reserve is raising interest rates aggressively to tame inflation.

“A lot of it is dollar strength rather than rupee weakness,” said Rahul Bajoria, the chief economist for India at Barclays. “It still feels like on a relative basis the rupee has done a lot better,” he said, pointing to the steeper declines in the value of the euro and the British pound against the dollar.

On Tuesday, the rupee briefly crossed 80 to the dollar for the first time. The Reserve Bank of India intervened in the market, as it has in recent months, to bid up the currency, according to local media reports.

Like in much of the world, inflation has slowed economic growth this year in India. Reserve Bank officials responded by unexpectedly raising rates in May, and then again in June, to 4.9 percent. But inflation remains around 7 percent, putting pressure on household budgets.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government has cut taxes on fuel and restricted exports of wheat and sugar. And it has bought more Russian oil, which has become cheaper following sanctions imposed by the United States and Europe.

https://finance.yahoo.com/news/india-rupee-drops-another-record-035250125.html

The rupee declined to as low as 80.06 per dollar on Tuesday before reversing losses as traders cited possible central bank intervention. The currency has been buffeted by nearly $30 billion of foreign outflows from the nation’s equities so far this year -- a record sum -- and concerns over a deteriorating current-account deficit amid elevated oil and commodity prices.

India policymakers have sought to arrest the currency’s decline with a raft of measures -- from intervention to raising duties on gold imports -- with a weaker rupee adding to imported inflation pressures. Other emerging market currencies are also feeling the heat as a hawkish Federal Reserve lures capital toward the US.

“The risks for the rupee remain to weaken further,” said Dhiraj Nim, economist and FX strategist at Australia & New Zealand Banking Group Ltd. “Oil prices, especially, remain a bit volatile, while external headwinds on account of Fed tightening may continue. The trade imbalance also remains wide.”

India’s central bank sees the rupee as moving toward its fair value and will step in to sell dollars from its reserves when it assesses a genuine shortfall, according to people familiar with the matter. Traders cited RBI intervening in the forex market as the currency breached 80 to a dollar.

The currency has declined 7% this year as a shortfall in India’s current account -- the broadest measure of external finances -- will probably widen to 2.9% of gross domestic product in the fiscal year ending March 31, according to a Bloomberg survey in late June, nearly double the level seen in the previous year. The rupee ended little changed at 79.95 a dollar on Tuesday.

India’s central bank is for an orderly appreciation or depreciation in the currency and is intervening in all market segments to curb volatility, Governor Shaktikanta Das said earlier this month.

Strategists at Nomura Holdings Inc and Morgan Stanley continue to remain bearish on the rupee, forecasting the currency may decline to 82 to a dollar by September. Options pricing suggest that there is 67% probability for the rupee to decline to that level between now and end-December, up from 50% at the start of July.

The Reserve Bank of India has foreign-exchange reserves of almost $600 billion, which it has been deploying to protect the rupee. Authorities have raised duties on gold import and raised levies on petroleum exports. The monetary authority has also announced measures to draw more forex inflows into the country and allowed rupee settlement of trade.

In earnings call after earnings call, U.S. corporate leaders are delivering the same warning—that the strong U.S. dollar will be a drag on their profits.

“The dollar might have even had a stronger quarter than we did, which is kind of amazing,” said Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff on the company's May 31 earnings call, explaining why the company was lowering its sales guidance.

During the company's second quarter earnings call on Monday, IBM CFO Jim Kavanaugh said it wasn't "immune" to the strong dollar, "especially when currencies move at the rate, breadth, and magnitude that we've seen." IBM said the strong dollar is likely to wipe $3.5 billion off its full-year revenue, sending shares 6.9% lower in early trading on Tuesday.

Netflix CFO Spencer Neumann on Tuesday told investors that "the strengthening of the U.S. dollar is a major outlier, and we just need to kind of work through that." Netflix blamed a strong dollar for their Q2 revenue growth coming in below its forecast; it reported an increase of 8.6% versus a forecast of 9.7%.

On Tuesday, pharmaceutical manufacturer Johnson & Johnson cut its full-year profit guidance, saying that the strong dollar might lower its sales overseas.

Microsoft also trimmed its revenue forecasts based on the strengthening dollar.

An analysis from Bloomberg found that references to “foreign exchange” in earnings calls have hit a three-year high this season.

USD to euro near parity

The U.S. dollar has gained against almost every other currency in recent months. It’s up 11% versus the euro so far this year, with the exchange rate between the two currencies hitting parity for the first time in 20 years. The USD is also up 13% against the British pound, 20% against the Japanese yen, and 6% against the Chinese renminbi. The U.S. Federal Reserve's interest rate hikes are helping drive up the value of the U.S. dollar, and traders are seeking safety in the U.S. dollar and U.S. assets amid geopolitical uncertainty.

The strong U.S. dollar is a windfall for some holders of the currency, like U.S. tourists on shopping sprees in Europe. But it can weigh on corporate earnings, especially at firms that do a sizable share of their business overseas.

Why is a strong USD bad for corporate earnings?

A strong USD makes U.S. manufactured goods more expensive overseas, so foreign buyers need more local currency to pay for the U.S.-made items they bring into other countries. The rising cost of U.S. goods in foreign currencies incentivizes importers to seek goods made elsewhere, disadvantaging U.S. manufacturers. U.S. companies may try to cut costs to keep their prices competitive and preserve their margins.

A strong dollar also deflates the value of revenue generated overseas once it's converted into U.S. dollars. That poor conversion rate can hit the bottom line of U.S. companies that do a lot of their business in foreign markets, like the U.S. tech sector, which generates 60% of its revenue in foreign markets, according to Goldman Sachs.

Together, these factors can exert a small but visible drag on corporate earnings. Credit Suisse estimates that a 8-10% increase in the dollar’s value leads to a 1% fall in U.S. corporate profits.

Analysis by Andy Mukherjee | Bloomberg

https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/a-usrecession-will-also-come-to-indias-tech-hub/2022/07/25/0e4e899e-0bd6-11ed-88e8-c58dc3dbaee2_story.html

Look closer at the financial results of IT firms, and you’ll see signs of stagflation in plummeting profitability. Infosys managed to boost rupee earnings by just over 3% from a year earlier in the June quarter, even with nearly 24% revenue growth. A 20% EBIT margin — earnings before interest and tax as percentage of revenue — is a 3.6 percentage point drop year on year. In fact, it’s even worse than what the bellwether outsourcing firm was garnering immediately before the pandemic gave a big lift to the business.

At Infosys’s traditional Bengaluru rival, Wipro Ltd., the EBIT margin fell to its lowest since the September 2018 quarter. Partly that was because it signed up 15,000-plus net new employees, including 10,000 fresh graduates in three months through June 30. (Infosys bumped up its headcount by more than 20,000 during the same period.) But then again, competitor HCL Technologies Ltd., which hit the brakes by slashing quarterly net hiring by almost four-fifths to about 2,000, also saw a lower-than-expected EBIT margin of 17%, a multiyear low.

The margin at Tata Consultancy Services Ltd., the biggest Indian IT vendor, was better at 23.1%, but it was still 2.4 percentage points narrower than for the June quarter of 2021. TCS management has indicated that $7 billion to $9 billion worth of quarterly deal wins could be a sustainable rate. That’s “flattish” from a year-on-year growth basis, Nomura says.

Profitability might remain under pressure for the rest of this year — both because of a slowdown in the West, and the way the industry is structured in India. Offshoring is profitable, but the people it employs won’t stay on their jobs forever without onsite postings at client locations and dollar wages. With the pandemic over, travel and visa expenses are adding up. But the Indian vendors will struggle to get paid more — customers will cite the near-7% drop this year in the rupee as a reason to not bump up the dollar price of contracts. The exchange-rate advantage, however, will be insufficient to make up for the rising pressure of rupee costs.

For one thing, salary increases can’t be skimped on: TCS employs more than 600,000 people, but its attrition rate is almost touching 20%, more than double from a year earlier. Employee retention appears to be even more challenging at Infosys, where attrition surged past 28% in the June quarter. Startups that target India’s local e-commerce or fintech markets compete for the same programmers as the software exporters. While small, private-equity-funded firms are turning cautious about burning cash on payroll, an employers’ market for coding talent is perhaps a story for next year. With India’s domestic inflation rate at 7%, IT services firms have little scope for belt-tightening on wage costs.

Ultimately, all of them will resort to “pyramiding” to protect their margins. It basically means putting a lot of inexperienced code-writers under an experienced project manager and hoping that the client will still come out happy. But since rookies’ productivity has its limits, the more complicated programming will have to be sub-contracted to smaller vendors. The costs of doing that are rising as well.

Former Reserve Bank of India Governor Raghuram Rajan on Saturday said India's future lies in strengthening liberal democracy and its institutions as it is essential for achieving economic growth.

Warning against majoritarianism, he said Sri Lanka was an example of what happens when a country's politicians try to deflect a job crisis by targeting minorities.

Speaking at the 5th conclave of All India Professionals Congress, a wing of the Congress party, in Raipur, he said any attempt to turn a large minority into "second class citizens" will divide the country.

Mr Rajan was speaking on the topic 'Why liberal democracy is needed for India's economic development'.

".What is happening to liberal democracy in this country and is it really that necessary for Indian development? ... We absolutely must strengthen it. There is a feeling among some quarters in India today that democracy holds back India ... India needs strong, even authoritarian, leadership with few checks and balances on it to grow and we seem to be drifting in this direction," Mr Rajan said.

"I believe this argument is totally wrong. It's based on an outdated model of development that emphasizes goods and capital, not people and ideas," said the former chief economist of the International Monetary Fund.

The under-performance of the country in terms of economic growth "seems to indicate the path we are going on needs rethinking," he said.

The former RBI governor further said that "our future lies in strengthening our liberal democracy and its institutions, not weakening them, and this is in fact essential for our growth."

Elaborating on why majoritarian authoritarianism must be defeated, he said any attempt to "make second class citizens of a large minority will divide the country and create internal resentment." It will also make the country vulnerable to foreign meddling, Me Rajan added.

Referring to the ongoing crisis in Sri Lanka, he said the island nation was seeing the "consequences when a country's politicians try to deflect from the inability to create jobs by attacking a minority." This does not lead to any good, he said.

Liberalism was not an entire religion and the essence of every major religion was to seek out that which is good in everyone, which, in many ways, was also the essence of liberal democracy, Mr Rajan said.

Claiming that India's slow growth was not just due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Mr Rajan said the country's underperformance predated it.

"Indeed for about a decade, probably since the onset of the global financial crisis, we haven't been doing as well as we could. The key measure of this underperformance is our inability to create the good jobs that our youth need," the former RBI governor said.

Kaushik Basu

@kaushikcbasu

IMF's just-released World Economic Outlook shows, over 3 years, 2020-2, India's annual growth is 2.9%, behind China (4.5%) & low-income country average (3.1%). This is not where India was; its economy has enough strength. This is the price of divisive politics & erosion of trust.

https://twitter.com/kaushikcbasu/status/1552926615662985216?s=20&t=VXI6HwUCK9o_mKUrecMonA

India’s trade deficit ballooned to a record high in July, as elevated commodity prices and a weak rupee inflated the country’s import bill.

The gap between exports and imports widened to $31.02 billion in July, from $26.18 billion in June, B.V.R Subrahmanyam, India’s trade secretary, told reporters at a briefing in New Delhi Tuesday, citing preliminary data. The trade deficit in June was a record before the latest numbers were released.

India's record high trade deficit in July signals a further deterioration in the country's external balances, which is likely to keep the rupee under pressure, analysts said on Wednesday.

Trade deficit in Asia's third largest economy widened to an all-time high of $31 billion, data on Tuesday showed, prompting concerns about the country's ability to fund its current account deficit and hurting the outlook for the rupee.

"I think after looking at the July trade deficit, we need to re-work on our CAD and BoP number, and thus the view on the rupee", Vikas Bajaj, head of currency derivatives at Kotak Securities, said.

Bajaj pointed out that until now the market consensus for India's current account deficit (CAD) was around $100 billion for the current fiscal year ending in March.

"But this definitely looks out of whack after July's trade number," he said.

In a note on Wednesday, QuantEco Research revised their CAD projections higher for the current fiscal year to $130 billion from $105 billion and the balance of payments (BoP) estimate to $60 billion from $35 billion.

The partially convertible rupee was trading at 79.02 per U.S. dollar in afternoon trade, 0.4% weaker on the day. On Tuesday, the unit had touched 78.49, its highest level since June 28. The local currency hit a record low of 80.0650 on July 19.

Vivek Kumar, a economist at QuantEco, said the recent recovery in the rupee from 80 will prove to be temporary and expects the local unit to fall to 81 to the dollar in the current fiscal year.

Bajaj said the recovery on the rupee was "broadly done" and that the currency "should once again see slow and steady move towards 80+ levels".

Pakistan is scrambling for a bailout to avert a debt default as its currency plummets. Bangladesh has sought a preemptive loan from the International Monetary Fund. Sri Lanka has defaulted on its sovereign debt and its government has collapsed. Even India has seen the rupee plunge to all-time lows as its trade deficit balloons.

Economic and political turbulence is rattling South Asia this summer, drawing chilling comparisons to the turmoil that engulfed neighbors to the east a quarter century ago in what became known as the Asian Financial Crisis.

By Arsh Tushar Mogre

BENGALURU (Reuters) - India likely recorded strong double-digit economic growth in the last quarter but economists polled by Reuters expected the pace to more than halve this quarter and slow further toward the end of the year as interest rates rise.

Asia's third-largest economy is grappling with persistently high unemployment and inflation, which has been running above the top of the Reserve Bank of India's tolerance band all year and is set to do so for the rest of 2022.

Growth this quarter is predicted to slow sharply to an annual 6.2% from a median forecast of 15.2% in Q2, supported mainly by statistical comparisons with a year ago rather than new momentum, before decelerating further to 4.5% in October-December.

- ADVERTISEMENT -

The median expectation for 2022 growth was 7.2%, according to an Aug. 22-26 Reuters poll, but economists said that the solid growth rate masks how rapidly the economy was expected to slow in coming months.

"Even as India remains the fastest-growing major economy, domestic consumption will perhaps not be strong enough to drive growth further as unemployment remains high and real wages are at a record low level," said Kunal Kundu, India economist at Societe Generale.

"By supporting growth through investment, the government has only fired on one engine while forgetting about the impetus which domestic consumption provides. This is why India's growth is still below its pre-pandemic trend."

The economy has not grown fast enough to accommodate some 12 million people joining the labour force each year.

Meanwhile the RBI, a relative laggard in the global tightening cycle, is set to raise its key repo rate by another 60 basis points by the end of March to try to bring inflation within the tolerance limit. [ECILT/IN]

That follows three interest rate rises this year totalling 140 basis points, and would take the repo rate to 6.00% by end-Q1 2023.

While the central bank's mandated target band is 2%-6%, inflation was expected to average 6.9% and 6.2% this quarter and next, respectively, before falling just below the top end of the range to 5.8% in Q1 2023. That is roughly in line with the central bank's projection.

"Despite signs of a cool-off in price pressures ... it is premature to go easy on the inflation fight given considerable uncertainties from geopolitical risks and hard landing risks in major economies," said Radhika Rao, senior economist at DBS.

The economy is also enduring inflation pressure from a weak rupee, which for months has been trading close to 80 to the U.S. dollar, a level the central bank has been defending in currency markets by selling dollar reserves.

The latest Reuters poll also showed India's current account deficit swelling to 3.1% of gross domestic product this year, the highest in at least a decade, which may put further pressure on the currency.

@RiteshEconomist

We shouldn't get carried away by 13.5% #GDPgrowth in Q1 FY2022/23.

Q1FY2020/21: INR 35.5 trillion

Q1FY2022/23: INR 36.85 trillion

The increase in 3 years: INR 1.35 trillion or 3.9% in 3 years.

#economy #India #IndiaAt75

@EconomicTimes

https://twitter.com/RiteshEconomist/status/1564989770966523905?s=20&t=Xfj8WjDj-wkroo8JTkhBxQ

--------

Q1 GDP growth misses estimates despite low base; govt spending subdued

13.5% expansion in June QTR despite low base; GVA at basic prices up 12.7%

https://www.business-standard.com/article/economy-policy/q1-gdp-growth-misses-estimates-despite-low-base-govt-spending-subdued-122083101151_1.html

Keeping the two pandemic years of 2020 and 2021 out, Q1 real GDP in 2022-23 is only 3.8 per cent higher than in the equivalent quarter of 2019-20. Gross value added (GVA) at basic prices grew at 12.7 per cent in the June quarter while nominal GDP was up 26.7 per cent, reflecting elevated inflationary pressures in the economy.

Growth in private final consumption expenditure, or private spending, grew at a robust 25.9 per cent with pent-up demand kicking in as consumers felt confident to spend. Government spending, however, grew only 1.3 per cent, signalling that both the Central and state governments kept their expenditure in check during the quarter.

Gross fixed capital formation (GFCF), which represents investment demand in the economy, grew at a robust 20.1 per cent. However, compared to the pre-pandemic period of FY20, GFCF grew only 6.7 per cent.

On the supply side, manufacturing grew by a disappointing 4.8 per cent. Despite 25.7 per cent growth in trade, hotel, transport services, the sector, with the highest contribution to GDP, is still 15.5 per cent below the pre-pandemic level of the equivalent quarter in FY20.

The labour-intensive construction sector grew 16.8 per cent but it is barely above the pre-pandemic level, growing 1.2 per cent.

Madhavi Arora, lead economist, Emkay Global Financial Services, said. “We maintain growth may remain at 7 per cent for the year, albeit with downside risks. Going ahead, even as recovery in domestic economic activity is yet to be broad-based, global drags in the form of still elevated prices, shrinking corporate profitability, demand-curbing monetary policies and diminishing global growth prospects weigh on the growth outlook.”

Nikhil Gupta, chief economist of Motilal Oswal, said assuming no change in projections by the RBI for the rest of the year, the first-quarter data suggested the central bank’s FY23 growth forecast would be revised to 6.7 per cent from 7.2 per cent.

The RBI expected 16.2 per cent growth in Q1, with 6.2, 4.1, and 4 per cent growth in the subsequent quarters.

Aurodeep Nandi, India economist and vice-president at Nomura, said even if one were to discount the low base, this marked a stellar rise in sequential momentum with post-pandemic tailwinds lifting GDP growth in the June quarter.

https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/india-inflation-basket-needs-urgent-revision-economists-say-1.1817674

“Higher the weightage of food in overall CPI, the more cumbersome it is for monetary policy to contain inflation,” economists including Deepak Mishra and Ashok Gulati wrote. “The structure of headline inflation in India is quite different from the advanced economies which limits the efficacy of monetary policy in India,” they wrote.

Food and beverages constitute nearly 46% of India’s CPI basket. This is in contrast to many advanced economies where food weights are much lower, such as UK’s 9.3%, US’ 13.2% and Canada’s 15.94%.

The Reserve Bank of India uses retail inflation as a benchmark to set borrowing costs and targets inflation between 2%-6%. Prices have stayed above its mandated range since the beginning of the year, raising a clamor to update the consumer price inflation basket that has not been revised for over a decade.

“This corroborates the urgency to revise CPI with the latest consumption survey weights,” the researchers said. Policy measures need to focus on various supply-side bottlenecks, especially in food items which could be managed by increasing productivity by investing in research and development in agriculture, they said.

India’s Forex reserve lose $80 bn in 8 months as RBI defends rupee, quarterly CAD at alarming level

https://youtu.be/NXns1Im7QNg

------------

Indias foreign exchange reserves fall to lowest in 23 months

https://www.business-standard.com/article/finance/india-s-forex-reserves-fall-8-billion-in-a-week-as-rbi-defends-rupee-122090901004_1.html

The Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI’s) headline foreign exchange reserves declined by $7.9 billion to $553.11 billion in the week ended September 2, the latest central bank data showed.

The reserves are at their lowest since October 9, 2020, the RBI data showed. Analysts cited the RBI’s defence of the rupee through dollar sales amid a globally strengthening greenback as one of the reasons for the fall in reserves.

Incidentally, during the week that ended September 2, the rupee marked a fresh intraday low of 80.13 per US dollar.

-------------

Why are India's foreign reserves depleting, and what could it mean for the country? - BusinessToday

https://www.businesstoday.in/latest/economy/story/why-are-indias-foreign-reserves-depleting-and-what-could-it-mean-for-the-country-347234-2022-09-14

For the U.S., a stronger dollar means cheaper imports, a tailwind for efforts to contain inflation, and record relative purchasing power for Americans. But the rest of the world is straining under the dollar’s rise.

“I think it’s early days yet,” said Raghuram Rajan, a finance professor at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business. When he served as governor of the Reserve Bank of India last decade, he complained loudly about how Fed policy and a strong dollar hit the rest of the world. “We’re going to be in a high-rates regime for some time. The fragilities will build up.”

-------------

The U.S. dollar is experiencing a once-in-a-generation rally, a surge that threatens to exacerbate a slowdown in growth and amplify inflation headaches for global central banks.

The dollar’s role as the primary currency used in global trade and finance means its fluctuations have widespread impacts. The currency’s strength is being felt in the fuel and food shortages in Sri Lanka, in Europe’s record inflation and in Japan’s exploding trade deficit.

This week, investors are closely watching the outcome of the Federal Reserve’s policy meeting for clues about the dollar’s trajectory. The U.S. central bank is expected Wednesday to raise interest rates by at least 0.75 percentage point as it fights inflation—likely fueling further gains in the greenback.

In a worrying sign, attempts from policy makers in China, Japan and Europe to defend their currencies are largely failing in the face of the dollar’s unrelenting rise.

Last week, the dollar steamrolled through a key level against the Chinese yuan, with one dollar buying more than 7 yuan for the first time since 2020. Japanese officials, who had previously stood aside as the yen lost one-fifth of its value this year, began to fret publicly that markets were going too far.

The ICE U.S. Dollar Index, which measures the currency against a basket of its biggest trading partners, has risen more than 14% in 2022, on track for its best year since the index’s launch in 1985. The euro, Japanese yen and British pound have fallen to multidecade lows against the greenback. Emerging-market currencies have been battered: The Egyptian pound has fallen 18%, the Hungarian forint is down 20% and the South African rand has lost 9.4%.

The dollar’s rise this year is being fueled by the Fed’s aggressive interest-rate increases, which have encouraged global investors to pull money out of other markets to invest in higher-yielding U.S. assets. Recent economic data suggest that U.S. inflation remains stubbornly high, strengthening the case for more Fed rate increases and an even stronger dollar.

Dismal economic prospects for the rest of the world are also boosting the greenback. Europe is on the front lines of an economic war with Russia. China is facing its biggest slowdown in years as a multidecade property boom unravels.

For the U.S., a stronger dollar means cheaper imports, a tailwind for efforts to contain inflation, and record relative purchasing power for Americans. But the rest of the world is straining under the dollar’s rise.

“I think it’s early days yet,” said Raghuram Rajan, a finance professor at the University of Chicago’s Booth School of Business. When he served as governor of the Reserve Bank of India last decade, he complained loudly about how Fed policy and a strong dollar hit the rest of the world. “We’re going to be in a high-rates regime for some time. The fragilities will build up.”

-------------

-------

On Thursday, the World Bank warned that the global economy was heading toward recession and “a string of financial crises in emerging market and developing economies that would do them lasting harm.”

The stark message adds to concerns that financial pressures are widening for emerging markets outside of well-known weak links such as Sri Lanka and Pakistan that have already sought help from the International Monetary Fund. Serbia became the latest to open talks with the IMF last week.

“Many countries have not been through a cycle of much higher interest rates since the 1990s. There’s a lot of debt out there augmented by the borrowing in the pandemic,” said Mr. Rajan. Stress in emerging markets will widen, he added. “It’s not going to be contained.”

A stronger dollar makes the debts that emerging-market governments and companies have taken out in U.S. dollars more expensive to pay back. Emerging-market governments have $83 billion in U.S. dollar debt coming due by the end of next year, according to data from the Institute of International Finance that covers 32 countries.

https://www.cmie.com/kommon/bin/sr.php?kall=warticle&dt=20220916161346&msec=236#:~:text=India's%20current%20account%20deficit%20(CAD,between%209%2D15%20September%202022.

India’s central bank raised its key interest rate by half a percentage point, as efforts to rein in inflation and protect an economic recovery have been complicated by its currency’s decline against the U.S. dollar.

On Friday, the Reserve Bank of India raised its overnight lending rate to 5.90% from 5.40%, the fourth increase since it began raising rates following an unscheduled meeting in May, prompted by global inflationary pressures exacerbated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

RBI Gov. Shaktikanta Das said that having witnessed the major shocks of the coronavirus pandemic and the conflict in Ukraine, the global economy is now in the midst of a third major shock arising from aggressive monetary policy tightening from advanced economies that is having spillover effects on the rest of the world.

“There is nervousness in financial markets with potential consequences for the real economy and financial stability,” Mr. Das said. “The global economy is indeed in the eye of a new storm.”

The pace at which the U.S. Federal Reserve has raised rates, coupled with growing fears of a global recession, have strengthened the dollar and heaped downward pressure on other currencies. The Fed approved its third consecutive interest-rate rise of 0.75 percentage point last week and signaled additional large increases as inflation remains stubbornly high. Central banks around the world continue to tighten their own monetary policy.

The British pound hit its lowest-ever level against the U.S. dollar this week as investors worried about the government’s plans to cut taxes and the Bank of England warned it would raise interest rates as much as needed to hit its inflation targets. The Chinese yuan slid to its weakest level against the dollar in more than a decade, and Japan intervened in the foreign-exchange market for the first time in 24 years to support the yen.

In India, the rupee is down about 9% this year against the dollar. Despite the RBI’s efforts to defend the currency, it slumped in July past 80 rupees per dollar to record lows. That defense has contributed to an almost $100 billion decrease in India’s foreign-exchange reserves over the past year to $545 billion. The RBI also attributes some of that decrease to the change in value of other currencies it holds.

Mr. Das said the global economic outlook remains bleak, with recession fears mounting and inflation persisting at “alarmingly high levels” across multiple jurisdictions.

“Central banks are charting new territory with aggressive rate hikes even if it entails sacrificing growth in the near-term,” he said.

Emerging-market economies in particular, Mr. Das said, are confronting challenges of slowing global growth, elevated food and energy prices, debt distress and sharp currency depreciations. Despite the unsettling global environment, he added, the Indian economy remains resilient.

Robert Carnell, Asia-Pacific chief economist at ING Bank, said a weak rupee was more troublesome from the point of view of imports becoming more expensive rather than from any external debt issue, given India’s debt levels remained relatively low.

Mahesh Vyas, the managing director of the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, said while the principal objective of the RBI’s currency intervention is to avoid volatility, support for the rupee for any given value is futile.

“Government efforts can delay the slide of the rupee but it cannot stop it,” he said.

The Indian rupee has declined in each of the ten months this year to notch its biggest losing streak in almost four decades as the U.S. Federal Reserve's hawkish stance on monetary policy catapulted the dollar to two-decade highs.

The dollar index is up 16% this year, having scaled 114.8-levels last month to trade near its 2002 peak. Its ascent has pressured currencies globally, especially ones in emerging Asian markets.

The Indian rupee fell 1.8% against the dollar in October, taking its slide for the year to nearly 11%.

Surging oil prices due to the Russia-Ukraine conflict and weakness in the Chinese yuan have only piled on more pressure on the rupee and helped send it to a record low of 83.29 per dollar earlier this month.

The rupee's losses have been deeper in the past two months, with market participants reckoning that the Reserve Bank of India let the currency slide after having helped hold it at the 79-80 levels for a long time.

Almost all traders and economists expect there will be no let-up in the pressure on the rupee for the rest of the year as the Fed stays on its aggressive rate-hike path after making fighting inflation its priority.

"This week, the Fed's upcoming meeting would be crucial for the rupee outlook. It could come under pressure in case Fed indicates aggressive tightening path in the future," HDFC Bank economists wrote in a note.

"Broadly, 81.80 to 82.00 seems a strong support zone for the USD/INR pair. As long as it trades above this convincingly, one can expect a U-turn towards 82.80 to 83.00 levels," said Amit Pabari, managing director at consultancy firm CR Forex Advisors.

The sharp decline of Asian currencies has sparked concerns within global financial markets over rising debt burdens among regional governments and corporate borrowers.

Asian countries are raising policy rates at a slower pace than the U.S. That, combined with deteriorating trade balances, has caused some Asian currencies to depreciate 10% or more against the dollar since the end of March.

The South Korean won has declined by 17% against the greenback during those seven months. The Philippine peso took a 12% hit. The Indian rupee is down by 10%, sinking below the level during the 1997 Asian currency crisis.

When the Vietnamese dong depreciated below the currency crisis level, the State Bank of Vietnam widened the daily exchange rate trading band to plus or minus 5% from 3%. The central bank may have faced increasing difficulty in defending the national currency.

Governments and businesses in emerging markets frequently take on debt denominated in the dollar or other foreign currencies. The overall debt in South Korea, India and Thailand is 70% denominated by foreign currencies, according to statistics from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. In the Philippines, the share is 97%.

Foreign-currency-denominated debt is preferred over debt denominated by domestic currency because of the typically lower interest rates for the former. On top of that, foreign-currency-denominated debt stands a better chance of drawing investors because of the reduced foreign exchange risk.

The funds raised by issuing debt are commonly converted into local currencies. But when it comes time to pay back the debt, the local currency needs to be translated back to the dollar, for example. If the local currency has grown weak, the government or the company needs to pay more in the local currency to settle the debt.

Amid fears debt obligations will swell, rates for credit default swaps have climbed. These rates serve as barometers for concern over nonpayment of debt.

The costs for five-year credit default swaps for government bonds have started to rise. The rates in the Philippines and Indonesia stand at 1.3% and 1.4%, respectively, more than doubling from the end of March and reaching a high not seen in two and a half years.

The credit default swap rate for South Korean government bonds has hit 0.7%, a level last seen in November 2017.

Credit default swap prices are on the rise for corporate debt too. The spread for the credit default swap index composed of 40 major Asian companies outside of Japan has expanded to an 11-year high of 2.3%.

"Investors are guarding against worsening credit worthiness due to the depreciating currencies," said Toru Nishihama, chief economist at the Dai-ichi Life Research Institute.

Equity markets have been conspicuously lackluster in Asia. The MSCI Asia ex Japan index is down 28% from the end of 2021. That compares unfavorably to the MSCI world index, which is off by 18%.

When these stock trends are paired with heavier debt payment loads, companies will have less access to funds to invest in growth.

For international investors trading in dollar-denominated assets, a drop-off in Asian currency values equates to diminishing dollar-based returns.

"If a currency is anticipated to depreciate, international investors will be less willing to invest in Asian stocks out of concerns over forex loss," said Kota Hirayama at SMBC Nikko Securities.

Because Asia is a global manufacturing center, weaker currencies normally lead to increased exports and improved corporate earnings. But worldwide interest rate hikes have opened up concerns over a recession that would undercut business performance.

https://www.reuters.com/world/india/indias-current-account-gap-widens-9-year-high-2022-12-29/

MUMBAI, Dec 29 (Reuters) - India's current account deficit widened in the July-September quarter as high commodity prices and a weak rupee increased the country's trade gap, data from the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) showed on Thursday.

In absolute terms, the current account deficit (CAD) (INCURA=ECI) was $36.40 billion in the second quarter of fiscal year 2022/23, its highest in more than a decade. As a percentage of GDP, it was 4.4%, its highest since the June quarter of 2013.

The CAD was $18.2 billion, or 2.2% of GDP, in the preceding April-June quarter, while the deficit was $9.7 billion, or 1.3% of GDP, in the same quarter a year earlier, the release showed.

In a statement, the RBI linked the widening deficit to the increase of "the merchandise trade deficit to $83.5 billion from $63.0 billion in Q1 2022/23 and an increase in net outgo under investment income".

In its Financial Stability Report released after the data, it said the widened trade deficit reflected "the impact of slowing global demand on exports, even as growth in services exports and remittances remained robust".

The median forecast of 18 economists in a Dec. 5-14 Reuters poll was for a $35.5 billion CAD in the July-September quarter.

The RBI said services exports reported growth of 30.2% on a year-on-year (y-o-y) basis, driven by exports of software, business and travel services, while net services receipts increased sequentially and y-o-y.

Private transfer receipts, mainly representing remittances by Indians employed overseas, rose by 29.7% to $27.4 billion from a year earlier.

https://www.reuters.com/world/india/indias-surging-services-exports-may-shield-economy-external-risks-2023-04-03/

IT services still accounted for 45% of India's total services exports in April-December.

Professional and management consulting grew the fastest - at a 29% compounded annual growth rate over the last three years, as per estimates by economists at HSBC Securities and Capital Markets.

The recent growth in services exports has been largely powered by global capability centres, which have started to offer global clients a range of high-end and critical solutions such as accounting and legal support.

----------------

This, together with a drop in merchandise trade deficit, resulted in the current account deficit shrinking more than expected to $18.2 billion, or 2.2% of GDP.

---------------

A surge in India's services exports, which hit a record high in the October-December quarter, is expected to shield the economy from external risks as a slowing global economy will likely weigh on the country's merchandise exports.

Service exports are no longer being driven by IT services alone but also by more lucrative offerings such as consulting and research and development, analysts and economists told Reuters.

India's services exports rose 24.5% on year in October-December 2022, hitting a record $83.4 billion during the quarter, data released by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) on Friday showed.

The services surplus, which deducts any imports in the category, also rose 39.21% to a record $38.7 billion.

This, together with a drop in merchandise trade deficit, resulted in the current account deficit shrinking more than expected to $18.2 billion, or 2.2% of GDP.

"We expect services exports to grow to over $375 billion by March 2024, as compared to $320-350 billion for the year ending March 2023," said Sunil Talati, chairman of the Services Export Promotion Council.

Services exports will likely surpass goods exports by March 2025, he said.

October-December merchandise exports stood at $105.6 billion, according to latest RBI data.

------------

As a result, such exports will hold up better compared to goods exports in the face of a weakening global economy, analysts said.

Over the last two to three years, there has been a rapid growth in global capability centres, said Sangeeta Gupta, chief strategy officer at software industry lobby group Nasscom.

Nasscom estimates that India is home to over 45% of such global capability centres in the world.

According to Pranjul Bhandari, chief India economist at HSBC Securities and Capital Markets, such centres started off providing support functions, but they have now moved up the ladder to tech enablement, business operations, capability development, and even R&D and business development.

While U.S. companies were the first movers in India, a lot of companies from Europe, Australia and Asia are also exploring stepping up their operations, Nasscom's Gupta said.

An acceleration in digitalisation after the Covid crisis and a lack of adequate tech talent in some of these countries are key factors, she added.

Sectors such as tourism, education, financial services and health also contributed to India's higher service exports.

https://www.reuters.com/business/finance/indias-forex-reserves-post-steepest-weekly-decline-over-6-months-2023-08-25/

MUMBAI, Aug 25 (Reuters) - India's foreign exchange reserves (INFXR=ECI) declined to a near two-month low of $594.89 billion as of Aug. 18 and posted their steepest weekly fall in more than six months, data from the country's central bank showed on Friday.

They fell by $7.27 billion from the prior week, the sharpest decline since the week ended Feb. 10.

The changes in foreign currency assets, expressed in dollar terms, include the effects of appreciation or depreciation of other currencies held in the Reserve Bank of India's (RBI) reserves.

The forex reserves include India's Reserve Tranche position in the International Monetary Fund.

The RBI also intervenes in the spot and forwards markets to prevent runaway moves in the rupee.

In the week for which the forex reserves data pertains, the rupee dropped to a 10-month low of 83.16 against the U.S. dollar, prompting intervention from the RBI, as per traders.

Earlier this week, RBI Governor Shaktikanta Das reiterated that the central bank has no specific target for the rupee.

India's current account deficit widened to $13.4 billion in Q4FY22, which is 1.5% of GDP. The capital account deficit was $1.7 billion in Q4FY22, which was the first deficit since the Taper Tantrum episode in September 2013.

The current account tracks the flow of imports and exports.

A current account deficit occurs when the inflow of foreign currency from exports is less than the outflow of foreign currency from imports.

The capital account tracks the flow of assets and liabilities.

A capital account deficit occurs when the debit items are more than the credit items. This indicates a net outflow of capital from the country.

The sum of the current and capital accounts is always zero. This means that when a country has a deficit in its current account, it necessarily has a surplus in its capital account and vice versa.

India generally has a capital account surplus because it attracts a large share of foreign investments.

https://prepp.in/news/e-492-capital-account-indian-economy-notes

https://www.barrons.com/articles/india-bureaucracy-will-hold-back-economic-growth-a9354f77

To develop a connected national market, the Indian government is building motorways, airports, and railroads to stimulate material and people movements between states. However, even when this new infrastructure is put in place, there will be wide gaps between states. GDP per person in Uttar Pradesh is around $4,000, compared to $10,000 in Kerala.

Besides the income gap, there is a cultural gap. Unlike China, where 92% of the population belongs to the Mandarin-speaking Han ethnic group, India has a very diverse population that speaks many languages. Cultural differences, language problems, and state-specific business regulations make expanding a business from one state to another a challenge.