Greece Boat Tragedy: Are Pakistani Migrants Fleeing Hunger and Poverty?

The extensive news coverage of the loss of Pakistani migrants' lives in the recent Greece boat tragedy has linked it to "hunger" in Pakistan. The essence of these news stories is captured by a quote in a CNN headline: "We'll die of hunger anyway". It is attributed to a young man from the Pakistani town of Gujarat who is unfortunately believed to have drowned in the Mediterranean on his way to Greece. These stories beg the following questions: Is it really true that Pakistani migrants are fleeing hunger and poverty? How can people suffering from hunger afford to pay thousands of dollars to human smugglers to leave for greener pastures?

|

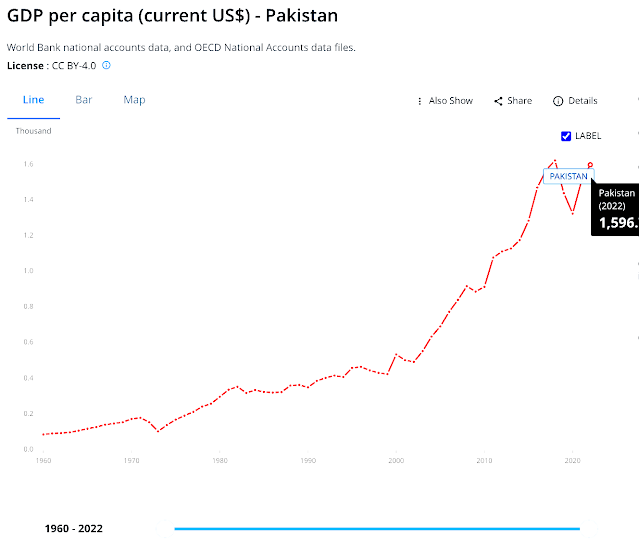

| Pakistan Per Capita GDP. Source: World BankPakistan's GDP per capita is about $1,600 |

The above questions are answered by two recent studies released by the Center for Global Development as follows: As GDP per capita rises, so do emigration rates. Emigration is seen as an investment as migrants are better-educated and richer than others. A similar 2010 study by the African Development Bank on emigration found that the share of migrants from sub-Saharan Africa remains low despite high levels of hunger and poverty in the region. Pakistan's rates of emigration have been rising along with GDP per capita growth over the last decade. It is currently about $1600 per person, according to the World Bank. Pakistan's latest economic survey reported that the per capita income in US dollar terms fell to $1,568 in FY23 from $1,766 in the previous year and $1,677 in FY21.

|

| Outward Migration of Pakistani Workers. Source: Pakistan Bureau of Emigration |

Two studies based on research by Michael Clemens and Mariapia Mendola released by the Center for Global Development (CGD) report that those who migrate are not among the world’s poorest. To the contrary, they find that migration is seen as an investment as migrants who are better-educated and richer than others. Here are the key points about migration as reported by the studies:

1. As GDP per capita rises, so do emigration rates. This relationship slows after roughly US$5,000, and reverses after roughly $10,000 (i.e. low- to middle-income, or the level of China or Mexico). Pakistan's current GDP per capita is about $1,600. Pakistan's latest economic survey reported that the per capita income in US dollar terms fell to $1,568 in FY23 from $1,766 in the previous year and $1,677 in FY21

.2. Successful, sustained economic growth in the low-income countries is therefore likely to raise the emigration rate, at least in the short-term. As incomes rise, so too does people’s ability to afford the investments that make migration easier.

3. These new migrants will not be among their countries poorest: in low-income countries, people actively preparing to emigrate have 30 percent higher incomes than the population on average, and 14 percent of these higher incomes come from more years of education.

“The world’s poorest are not the ones who migrate,” said co-author Mariapia Mendola, professor of economics the Università degli Studi di Milano Bicocca and Director of the Poverty and Development Program at Centro Studi Luca d’Agliano in Milan, according to the CGD. “Migration is seen as an investment, just like higher education. You wouldn’t decide not to send your kids to college just because your family is getting wealthier. Similarly, families are not deciding to stay put as their incomes rise. Migration changes lives and economies for the better.”

“This pattern is not new, or something to fear,” Michael Clemens, director of Migration, Displacement, and Humanitarian Policy and senior fellow at CGD, says. “As a poor country gets richer, at first more people emigrate, until the process eventually slows and reverses itself. We’ve seen it with Sweden a century ago and Mexico a half century ago. We’re seeing it now in Central America, and we’ll hopefully see the pattern emerge in sub-Saharan Africa as that region gets richer.”

A similar 2010 study by the African Development Bank on emigration found that the share of emigration from sub-Saharan Africa remains low despite high levels of poverty. Here's an excerpt of it:

"Results show that despite an increase in the absolute number of migrants, Africa, particularly SubSaharan Africa, has one of the lowest rate of emigration in the world .... Poorer countries generally have lower rates of emigration ......Bad socio-economic conditions generally seem to lead to higher rate of emigration by highly skilled individuals. Generally, migration is driven by motives to improve livelihoods with notable evidence of changes in labor market status."

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

South Asia Investor Review

Pakistan is the 7th Largest Source of Migrants in OECD Nations

Pakistani-Americans: Young, Well-educated and Prosperous

Pakistan is the Second Largest Source of Foreign Doctors in US & UK

Pakistan Remittance Soar 30X Since Year 2000

Pakistan's Growing Human Capital

Two Million Pakistanis Entering Job Market Every Year

Pakistan Projected to Be 7th Largest Consumer Market By 2030

Over 800,000 Pakistani Workers Migrated Overseas in 2022

Do South Asian Slums Offer Hope?

Comments

https://www.arabnews.com/node/2353346/pakistan

“Remittances inflows during July 23 were mainly sourced from Saudi Arabia ($486.7 million), United Arab Emirates ($315.1 million), United Kingdom ($305.7 million) and United States of America ($238.1) million respectively,” the SBP said in a statement.

----------------

Pakistan’s remittance flow declined by more than 7 percent in July on a month-on-month basis, the Pakistani central bank said on Thursday, with Saudi Arabia being the largest contributor.

The South Asian country recorded an inflow of $2 billion as part of remittances sent by Pakistanis working abroad, according to the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP).

However, the inflows recorded a huge drop of 19 percent on a year-on-year basis.

“Remittances inflows during July 23 were mainly sourced from Saudi Arabia ($486.7 million), United Arab Emirates ($315.1 million), United Kingdom ($305.7 million) and United States of America ($238.1) million respectively,” the SBP said in a statement.

Pakistan and Saudi Arabia have deep cultural, defense and economic ties, deeply rooted in history and religion. The Kingdom is home to over two million Pakistanis, making it the largest contributor to remittance inflows into the South Asian country.

The decline in remittances comes at a time when Pakistan is about to witness the transition of power to a caretaker government in August that would run the South Asian country for at least three months until a general election, due in November.

Embroiled in economic and political crises for more than a month, Pakistan secured a crucial $3 billion deal with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in late June after months of delay, with economists blaming the delay in signing the IMF deal for the economic turmoil.

Dr. Vaqar Ahmed, Joint Executive Director at the Sustainable Development Policy Institute (SDPI), said the government’s inability to sign a timely deal with the IMF had been damaging to the economy.

“During [Finance Minister Ishaq] Dar’s tenure, particularly three areas, energy prices, exchange rate, tax exemptions and also tax rates remained under the observations of IMF and conditions related to these areas became more stringent,” Ahmed told Arab News.

https://mixedmigration.org/pakistani-nationals-on-the-move-to-europe/

Are more people leaving Pakistan for Europe?

While it is not possible to extrapolate numbers from a single incident, even one of the most deadly disasters in the Mediterranean for many years, the broader data available on mixed migration to Europe confirms that movement from Pakistan has significantly increased in 2023. While Pakistan did not even feature in IOM’s ranking of the top ten countries of origin among arrivals in Europe in 2022, Pakistan was the fifth most represented country in the first half of 2023, with 5,342 arrivals. However, in Greece, there has been no significant recorded increase of Pakistani nationals between 2022 and 2023. Instead, there has been a sharp uptick in the number of Pakistani arrivals registered in Italy: while in 2022 Pakistani nationals comprised just 3 per cent of the total number of arrivals in Italy, according to UNHCR, so far in 2023 this proportion has risen to around 10 per cent.

Why are they choosing to leave?

Though the absolute numbers of Pakistani refugees, migrants and asylum seekers entering Europe are still relatively modest, if looked at long-term, it is important to understand what may have caused this recent spike. Previous research by MMC, drawing on interviews with Pakistani arrivals in Italy between November 2019 and September 2021, identified a variety of intersecting factors that drove the need to migrate, with many (48%) citing multiple reasons for doing so, the most common being violence, insecurity and conflict (54%), lack of rights and freedom (36%) and economic reasons (33%). Given the deteriorating economic situation, high unemployment and runaway inflation, these factors are likely to have evolved, with desperation and lack of opportunity driving more to migrate. The devastation and displacement brought on by last year’s catastrophic flooding have only made matters worse.

Which routes are they taking?

Until recently, according to MMC’s research, the majority of Pakistani refugees, migrants and asylum seekers were travelling through Iran and Turkey before entering Europe through the Eastern Mediterranean route and the Western Balkans before moving on to Italy. Others travelled the less common sea route from Turkey to Italy. For most of those interviewed the journey was arduous and protracted, usually involving more than one means of transportation (89%) and in almost three-quarters of cases (72%) taking more than a year to reach Italy.

Over the last year, however, there has been a decided shift towards the Central Mediterranean route, prompted by a number of developments elsewhere. Crossings from Türkiye into Europe have fallen sharply as Greece has stepped up sea patrols and built a border fence along the Evros. These developments have been accompanied by violent pushbacks and systematic human rights abuses against refugees and migrants, including illegal detention, physical assault, theft and humiliation. On multiple occasions, this brutal treatment has proven fatal: in February 2022, for instance, the bodies of 12 people who had been pushed back from Greece were found on the Turkish border, frozen to death after being stripped of their clothes and shoes.

This strategy of deterrence, aiming at discouraging people by all possible means from entering the EU, is now being replicated in the Western Balkans. 2022 saw the highest number of arrivals in the Western Balkans since the so-called ‘migration crisis’ of 2015/16, with 144,118 attempts to cross borders between the EU and Western Balkans recorded during the year. However, at the same time countries in the region (frequently in response to pressure from the EU) began to put in place more restrictive migration policies to curb transit.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2024-10-31/pakistan-s-brightest-leave-at-record-pace-with-high-cost-of-living-pkr-drop?embedded-checkout=true

Economic hardship has pushed skilled workers to move abroad, hollowing out banks, hospitals and multinational companies.

One million skilled workers — doctors, engineers, accountants and managers, among others — left Pakistan over the past three years alone, according to a government tally. That makes Pakistan one of the top 10 countries for emigration.

Asad Ejaz Butt is one of Pakistan’s best and brightest. After completing graduate studies in Canada, the economist returned home with a drive to contribute to his home country and its development.

Yet prestigious jobs working under two finance ministers weren’t enough to pay the bills. Over the past few years, as Pakistan’s inflation outranked any other nation in Asia, Butt couldn’t afford basic necessities, including rent. So he left his highly coveted government job and moved back to North America — to buy time and complete another advanced degree.

------------------------

https://youtu.be/YAeOOpk0OEI?si=thP0nkD0AL5l-ZwU

A growing number of skilled workers are leaving Pakistan, seeking opportunities abroad as their country faces one of Asia’s highest inflation rates, rising food and energy prices and a devalued currency.

To address the dire economic situation, the government has implemented unpopular reforms, including raising corporate tax rates and utility prices. These measures are part of Pakistan’s latest $7 billion loan deal with the International Monetary Fund, aimed at averting national bankruptcy.

But the result of all this has been an increasing number of would-be taxpayers emigrating to wealthier nations. So what does that mean for the country’s economic and political prospects?