G20 Summit in India: Modi's Personal PR Extravaganza?

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi successfully transformed routine rotational G20 presidency into an extravagant personal PR exercise this week. The Indian mass media and the general public saw Mr. Modi's face plastered all over the Indian capital. Some analysts described it as the kickoff of the Indian leader's political campaign for national elections scheduled for next year. As Mr. Modi spoke of "one earth, one family, one future", his right-wing Hindutva allies continued their unhindered campaign of murder and mayhem against the Christian community in the Indian state of Manipur. Globally, too, Mr. Modi lived up to his reputation of "Divider In Chief" as the Chinese leader Xi Jinping and the Russian leader Vladimir Putin chose to stay away from the gathering attended by all the western leaders. Both China and Russia stand in the way of the continuation of centuries-old unchallenged western hegemony of the world.

|

| Modi: Hero of Hatred at G20. Source: India Today |

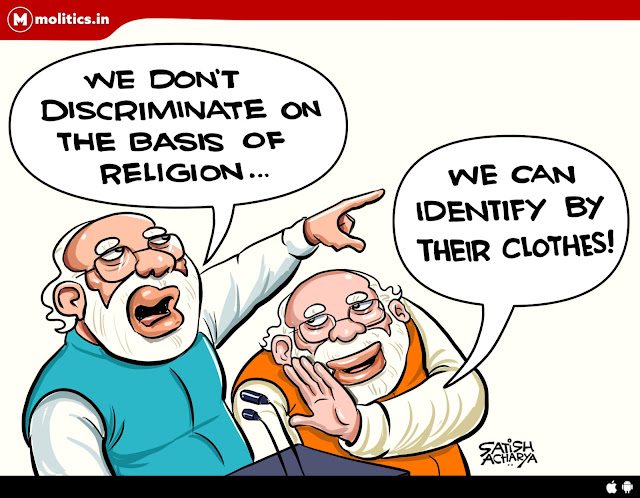

After the Gujarat anti-Muslim pogrom of 2002, Narendra Modi made the cover of India Today magazine with the caption "Hero of Hatred". Modi was denied a visa to visit the United States. The US visa ban on Modi was lifted in 2014 after he became prime minister. Since then, Narendra Modi's image has been rehabilitated by the West as the US and Western Europe seek allies in Asia to counter the rise of China. However, Modi's actions on the ground in India confirm that he remains "Hero of Hatred" and "Divider In Chief" at his core. A recent two-part BBC documentary explains this reality in significant detail. The first part focuses on the 2002 events in Gujarat when Modi as the state chief minister ordered the police to not stop the Hindu mobs murdering Muslims and burning their homes and businesses. The second part looks at Modi government's anti-Muslim policies, including the revocation of Kashmir's autonomy (article 370) and a new citizenship law (CAA 2019) that discriminates against Muslims. It shows the violent response by security forces to peaceful protests against the new laws, and interviews the family members of people who were killed in the 2020 Delhi riots orchestrated by Modi's allies.

|

| Modi Divider In Chief. Source: Time Magazine |

In a recent piece for Nikkei Asia, Indian journalist Swaminathan Aiyar dismisses Modi's attempts to recast himself as "Vishwaguru", the teacher of the world. Here's an excerpt of Aiyar's piece titled "India's Modi is not the world's guru":

"Modi's notion of being the world's guru is just as ridiculous as his twisted history of "centuries of enslavement," which has been used to attack India's religious minorities. A guru is nothing without disciples. If India or Modi himself is the world's guru, who are the disciples? The least likely candidates are Western powers which believe, rightly or wrongly, that they are the true global gurus. It might seem that India's disciples would be most likely to come from its geographic neighborhood rather than distant lands. But even a cursory examination shows otherwise. Does Pakistan regard India as a guru? No, it is India's greatest foe. It has allied with China, India's other major foe, to try and put India in its place. No disciples there. What about Bangladesh, which India helped to achieve independence from Pakistan in 1971? There is now little gratitude for India's help, which is accurately viewed as a ploy to split and disempower Pakistan rather than an altruistic move to aid Bangladeshis. Sri Lanka? Many there harbor ill will toward New Delhi in the belief that it supported the development of the Tamil Tiger insurgency when Indira Gandhi was India's prime minister in the early 1980s. The insurgency became a civil war in which up to 100,000 were killed. Hard to find disciples there. What about Nepal, a predominantly Hindu nation? Ever since then-Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru intervened in a royal power struggle in 1951, Nepalese have viewed New Delhi as an imperial power to be feared. India has on more than one occasion blocked essential supplies to Nepal to try to exert political influence. Nepalese may be Hindus, but they are anything but Modi's disciples"

| |

|

President Joseph R. Biden and other western leaders are making a huge mistake by coddling divisive and dangerous Modi. While the western nations are seeking an alliance with India to counter rising China, the Hindutva leadership of India has no intention of confronting China. In a piece titled “America’s Bad Bet on India”, Indian-American analyst Ashley Tellis noted that the Biden administration had “overlooked India’s democratic erosion and its unhelpful foreign policy choices” in the hopes that the US can “solicit” New Delhi’s “contributions toward coalition defense”.

Earlier this year, India's External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar confirmed New Delhi's unwillingness to confront China in an interview: “Look they (China) are a bigger economy. What am I going to do? As a smaller economy, I am going to pick up a fight with bigger economy? It is not a question of being a reactionary; it is a question of common sense.”

Modi's India is driven much more by a desire to bring back what the right-wing Hindus see as the "glory days" of India through "Hindu Raj" of the entire South Asia region, including Pakistan. The arms and technology being given to Modi will more likely be used against India's smaller neighbors, not against China.

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

South Asia Investor Review

Can Modi's India be Trusted with Nukes?

Balakot and Kashmir: Fact Checkers Expose Indian Lies

India's "Hindu Nazis" Join Forces With Western Neo-Nazis to Threaten World Peace

India is the Biggest Winner of Ukraine War and US-China Competition

Modi's Blunders and Delusions

Modi Coopting Chandrayaan Success For Hindutva Propaganda

Pakistani-American Journalist Questions Modi About Minorities in India

G20 in Kashmir: Modi's PR Ploy

Can Washington Trust Modi as a Key Ally?

Are India's Leaders Uneducated?

Vast Majority of Indians Believe Nuclear War Against Pakistan is Winnable

Comments

What you don’t see in the videos is also telling. You don’t see the Jama Masjid, one of the most iconic sites in the capital. I didn’t spot any churches. The Taj Mahal, India’s most famous landmark and heritage site, built by the Mughal dynasty that is reviled by the rulers of today, gets only a photo on one of the walls. The Golden Temple, the holiest shrine of Sikhs in India, gets a tiny video clip.

--------------------

You see him (Modi) not only at the airport and at the grand venue that was recently constructed to host the summit, but on practically every road, every few feet. Sometimes, two car lengths, at most. It’s a one-man show.

Having spent many of my growing and working years in New Delhi, the changes in the city for this mega event stand out.

Schools and offices were shut for the summit, roads blocked for so-called VIP movement. Sometimes you had to wait 15 minutes to cross a street as police cars barricaded them.

Vendors, otherwise ubiquitous on Indian streets and selling everything from fruits and vegetables to clothes, shoes and household items, were missing the past few days. They need a daily income from their sales to survive – but clearly don’t figure in the Modi government’s agenda to push India as the voice of the long-suffering Global South.

On some streets, there aren’t even the stray dogs that are a staple of all neighbourhoods. They, too, were rounded up.

But if Modi was the hero of the diplomatic extravaganza, monkeys were the designated menace. Life-sized cut-outs of langurs have been put up to scare the monkeys that can run rampage in Central Delhi, which hosts most major embassies and hotels, and is close to the summit venue.

The relatively heavy rain cooled temperatures in the capital but the partly flooded

roads also showed that you may spruce up the city but until you really fix the infrastructure, things are not really going to change.

It’s at the venue, however, that the deep stamp of Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) – which will stand for national elections next year – was most visible.

The old exhibition halls at Pragati Maidan – which means “field of progress” in Hindi and previously hosted anything and everything from international trade fairs to book fairs and auto shows – have been replaced with a grand new convention centre called the Bharat Mandapam. It’s a Sanskrit name, where Bharat refers to India, while a mandapam is the front porch of a Hindu temple.

Just with that name, the exhibition ground moves away from its secular, humdrum past.

The grounds are supposed to be the biggest exhibition space in the country. And as the official information tells you, there are more seats than the Sydney Opera House. But it’s next to one of the busiest roads in the city and near the Supreme Court of India, so it’s not really easy to get that many people to visit in one go anyway.

Unless the government pulls out all the stops to do just that.

The cavernous, warehouse-like halls have barren grey walls, currently hidden behind large G20 billboards and video clips of the different cultural trips the delegates and their spouses have undertaken in the past year.

The billboards are covered with images of the lotus flower. That is India’s national flower but it is also the BJP’s election symbol. And it is everywhere. Even in the official logo of the G20.

The video clips playing on the walls tell a story too. They show glimpses of Hampi – a UNESCO World Heritage site which was also the capital of a 14th-century Hindu empire – of Khajuraho temples and of the Nathdwara temple dedicated to the Hindu god Krishna’s avatar.

Analysis by Pankaj Mishra | Bloomberg

https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2023/09/11/modi-s-new-india-won-t-be-ally-to-the-west/439e5764-50f4-11ee-accf-88c266213aac_story.html

India is, suddenly, Bharat, and it could be asked, as Shakespeare wrote, what’s in a name? But Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who embraced the Sanskrit name for his country in the same week that he played lavish host to the G-20 summit in New Delhi, is trying hard to project India as a “vishwaguru” (guru to the world). It is time to examine his claims more closely, and also to see the present and the future of his “New India” without comforting illusions.

Take, for instance, the booklet, “Bharat, the Mother of Democracy,” presented by Modi’s government to visiting dignitaries at the G-20. According to it, ancient Hindu sages and kings were partisans of equality, inclusivity, and harmony. Even modern feminism was anticipated by the 5,000-year-old bronze statue of an “independent and liberated” dancing girl.

Such claims are part of an elaborate narrative that is decisively shaping the outlook of many Indians today — one in which a once-dynamic Hindu civilization was ravaged by vicious Muslims and exploitative Westerners.

In Modi’s own account, Hindus were enslaved by Muslim invaders for 750 years and then for an additional 250 years by white British colonialists — a version of history used in India today to justify the degradation of Muslim and Christian minorities, the destruction of mosques and British-built buildings, the purging of textbooks, and now the unofficial renaming of India.

Modi’s own popularity, unconnected to his party’s variable fortunes, stems from what is a potent promise in a country full of humiliated peoples: to destroy the corrupt old political order and, as he put it in his Independence Day speech last month, to ensure a fully modernized New India enjoys a “golden” period “for the next 1,000 years.”

Such millenarian bombast — also echoed in the speeches of Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping — belongs to a longer tradition of anti-Western demagogues proclaiming themselves heirs to distinguished ancient civilizations, including the Germans and Italians who sought to build the Thousand-Year Reich and the Third Rome, respectively.

It is a common mistake to suppose that German and Italians Fascists rejected modernity in favor of an idealized past. On the contrary, they pursued, often with help of Western nations they derided as “decadent,” ultra-modern technologies, modernist architectural plans, advanced transport systems and awesome public works. Like Hindu nationalists today, they used mass media, sporting events, and scientific breakthroughs to raise the pitch of collective emotion and project the image of a united and resurgent people.

Of course, since technological and military power still clearly lay with Britain, France and the US, the peoples failing to catch up with the West tried to feel superior to it in the realm of culture and philosophy. Invoking their great ethnic or racial past even as they sought grandiosely to supervise the future of the modern world, they became exemplars of what the American historian Jeffrey Herf has called “reactionary modernism.”

Presenting ancient Indians as pioneering democrats and feminists (also, the world’s earliest plastic surgeons), Modi belongs to this extended family of catch-up nationalists. His nation, too, seeks to blend neo-traditionalism with modernization while measuring itself, with volatile feelings of insecurity and resentment, against a weakened but still superior West.

Analysis by Pankaj Mishra | Bloomberg

https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2023/09/11/modi-s-new-india-won-t-be-ally-to-the-west/439e5764-50f4-11ee-accf-88c266213aac_story.html

It is no accident that Modi is a lifelong member of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), an organization that has, since the 1920s, deliberately modeled itself on the organizational structures and propaganda modes of anti-Western authoritarians. Moreover, nine years of BJP rule have confirmed that Hindu nationalists seek to remake Indian society as a forceful civilizational repudiation of Islam and the West.

This won’t change. Those hoping to recruit Modi’s Bharat as a Western ally should consider the plain historical fact that, as the scholar Nirad Chaudhuri wrote in 1954, the most ineradicable aspect of Hindu nationalism is “xenophobia, both personal and ideological.” The sentiment may be muted “when and where the military and political strength of the foreigner” is overwhelming but nevertheless thrives on an “incessant campaign of slander and denigration.”

Thus, there was nothing extraordinary about an Indian official effectively taunting Western countries on X, formerly known as Twitter, for the G-20’s failure to condemn Russia’s assault on Ukraine. Sweeping denunciations of the West as selfish and arrogant, deserving of a comeuppance, are now routine in India. More remarkably, as Modi’s ministerial colleagues as well as social media trolls go after George Soros, India is openly participating, for the first time in its long history, in the global networks of anti-Semitism.

Certainly, neither of the two main commonplaces about the world’s most populous nation — that it is a rising, vibrant democracy or that it is descending into authoritarianism — will seem adequate in the treacherous months and years ahead. More historically grounded analyses will be needed as yet another batch of reactionary modernists rises in the east.

That disparity was clear during the recent summit of the BRICS nations, which include Brazil, Russia and South Africa in addition to India and China. Even after Mr. Modi had spent a year promoting India as the voice of the global south, it was Mr. Xi who received the royal treatment.

In one video of a side meeting, the leaders, including Mr. Modi, all waited as Mr. Xi arrived to shake hands. They remained standing until after Mr. Xi had settled into a much larger seat than theirs — an entire sofa.

“Money talks,” said Ziyanda Stuurman, a senior analyst with the Eurasia Group’s Africa Team. “Whether it’s India or the U.S. or Europe, if they are not able to match or be as serious as China with rolling out funding, China will still enjoy this place of leadership.”

------------

A rising India has moved aggressively to champion developing nations, pursuing compromise in polarized times and promising to make America listen.

For more than a decade, China has courted developing countries frustrated with the West. Beijing’s rise from poverty was a source of inspiration. And as it challenged the postwar order, especially with its global focus on development through trade, loans and infrastructure projects, it sent billions of much-needed dollars to poor nations.

But now, China is facing competition from another Asian giant in the contest to lead what has come to be called the “global south.” A newly confident India is presenting itself as a different kind of leader for developing countries — one that is big, important and better positioned than China in an increasingly polarized world to push the West to alter its ways.

Exhibit A: the unexpected consensus India managed at the Group of 20 summit in New Delhi over the weekend.

With help from other developing nations, India persuaded the United States and Europe to soften a statement on the Russian invasion of Ukraine so the forum could focus on the concerns of poorer countries, including global debt and climate financing. India also presided over the most tangible result so far of its intensifying campaign to champion the global south: the admission of the African Union to the G20, putting it on par with the European Union.

“There is a structural shift happening in the global order,” said Kishore Mahbubani, a former ambassador for Singapore and author of “Has China Won?” “The power of the West is declining, and the weight and power of the global south — the world outside the West — is increasing.”

Only one country can be a bridge between “the West and the rest,” Mr. Mahbubani added, “and that’s India.”

At a time when a new Cold War of sorts between the United States and China seems to frame every global discussion, India’s pitch has clear appeal.

Neither the United States nor China is especially beloved among developing nations. The United States is criticized for focusing more on military might than economic assistance. The signature piece of China’s outreach — its Belt and Road infrastructure initiative — has fueled a backlash as Beijing has resisted renegotiating crushing debt that has left many countries facing the risk of default.

Subramanian Swamy

@Swamy39

If the G20 New Delhi Meeting is considered an organisational success, no one can deny it. But it was an unnecessary expenditure of the State revenue collected from tax payers merely for a two day conference. Finally except a feeble consensus nothing else was achieved.

https://x.com/Swamy39/status/1701565545995485497?s=20

Breakdown of how India spent RS.4,100 cr or nearly $500mn on the G20 summit and comparisons to past G20s

https://x.com/suhasinih/status/1701776907430506826?s=20

---------------------------

Thanks to G20, the capital is all spruced up. But at what cost? This was India’s first ever G20. and we spent a whopping Rs. 4100 Crore. How was the money spent? Watch the breakdown here.

https://www.indiatoday.in/newsmo/video/g20-summit-budget-india-has-spent-over-rs-4100-crore-heres-breakdown-2434521-2023-09-12

The southern states feel increasingly oppressed

https://www.economist.com/asia/2023/09/13/narendra-modi-is-widening-indias-fierce-regional-divides

Narendra modi likes to pull rabbits out of hats. One evening in 2016 the Indian prime minister declared that 500- and 1,000-rupee notes—representing 86% of cash by value—would cease to be legal tender by the end of the night. In 2020 he locked down the country at only a few hours’ notice. So it is hardly surprising that speculation has been running rampant since Mr Modi’s government announced that it is to convene a “special session” of Parliament, from September 18th to 22nd. What trick does he have up his sleeve now?

For the moment the guessing game has settled on two possibilities. One is that Mr Modi and his Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (bjp) will change the country’s name in English from India to Bharat (which is already the name in Hindi). The nameplate Mr Modi sat behind as he negotiated with g20 leaders at a summit over the weekend has added fuel to that theory. The other guess is that Mr Modi intends to reorganise the electoral calendar, so that India’s never-ending carnival of state and federal elections henceforth take place all at the same time, once every five years. In either case the change would serve a project Mr Modi has been pushing from the start: trying to centralise and homogenise a staggeringly vast and diverse country.

Since coming to power in 2014 the bjp has set about transforming India into something more like a European nation-state. That vision involves both strengthening the central government and promoting a pan-Indian, Hindu-nationalist identity. The government routinely emphasises that India is “one nation”, implementing policies such as “one nation, one ration card” (for subsidised grain) and proposing many more, such as “one nation, one uniform” (for the police). The idea of synchronising polls has been on the bjp’s manifesto since 2014. It is known as “one nation, one election”.

In economic matters, the government’s centralising tendencies are mostly very welcome. In 2017 Mr Modi introduced a national goods-and-services tax (“one nation, one tax”, better known as gst) seeking to deepen the country’s common market. It seems to be paying off. Between 2017-18 and 2020-21 the value of interstate trade increased by 44%, more than double the growth in gdp during the same period, according to a study in the Indian Public Policy Review, a journal. The paper’s authors attribute the increase to the introduction of gst and greater economic integration.

Moreover, the government is furiously building highways, commissioning new airports and launching zippy train services to knit Indians closer. The roll-out, over the past decade, of a national digital identity system and of digital payments has assuaged problems that sometimes caused headaches for Indians who travelled outside their own regions. It is getting easier to build businesses that span the country.

The southern states feel increasingly oppressed

https://www.economist.com/asia/2023/09/13/narendra-modi-is-widening-indias-fierce-regional-divides

It is plainly in India’s interests to forge a more sophisticated single market. Yet the government’s strident “one nation” rhetoric is causing some other ties to fray. The chief divide in India is between the industrialised, richer south, and the agrarian, impoverished north. The south is made up of five states: Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Telangana (see map). The north is home to two of the poorest ones, Uttar Pradesh (up) and Bihar. The south is richer, safer, healthier, better educated, and less awful to women and Dalits than the north (see chart). Bihar and up occupy the last and second-last positions when India’s states are ranked according to their scores on the human development index, a measure of well-being.

At the time of the last census in 2011 up and Bihar had 25% of India’s population, to the south’s 21%. The gap has grown. The latest official estimates suggest that in 2022 up and Bihar had 26% of India’s people, while the south’s share had declined to 19.5%. Their economies have also diverged. gdp per capita in the south is 4.2 times greater than in up and Bihar, up from 3.3 in 2011-12. The southern states contribute a quarter of India’s corporate- and income-tax revenues, compared with just 3% for up and Bihar. When companies such as Apple open new factories in India they head straight to the south, home to skilled workers and industry clusters.

Southern alarm bells

Politically, too, the north and south are different countries. No state in the south is ruled by a bjp government, which is seen as a party of the Hindi-speaking north. Karnataka, the only southern state where the bjp had made inroads, voted out Mr Modi’s party in elections earlier this year.

Regional differences are now causing tensions on three fronts: cultural, fiscal and political. Start with culture. The south has long resented what it sees as the imposition of values and language from the north. In 2019 Amit Shah, India’s home minister, tweeted that “if one language can do the work of uniting the country, then it is the most spoken language, Hindi.” In response protests broke out across the south, and even the bjp’s allies in the region distanced themselves from his comments. It is not just about words, explains R. Srinivasan of the Tamil Nadu state planning commission. Southern defenders of language also believe they are protecting a broader political identity, one that supports social justice, gender equality and emancipation from caste prejudice.

Complaints about India’s fiscal compact are growing, too. Though the central government rakes in revenue, states do much of the spending, particularly in crucial spheres such as education, health and welfare. The introduction of the gst weakened states’ revenue-raising powers. In 2021-22, spending by states accounted for 64% of public expenditure, but they raised only 38% of revenues. As a result, states are now more dependent than ever on transfers from the centre. How much they get is decided every five years by the Finance Commission, a constitutional body.

What each state receives varies depending on measures such as its population and level of development. As a result, southern states receive far less from the centre than they contribute. Redistribution across states is a feature of any federal system, a moral duty and, in India, a constitutional obligation. But it is becoming more controversial as state economies diverge. Concerns will probably redouble later this year, when the next finance commission starts working out how it will share revenues for the period 2027-32.

The southern states feel increasingly oppressed

https://www.economist.com/asia/2023/09/13/narendra-modi-is-widening-indias-fierce-regional-divides

The third and potentially most dangerous set of tensions relates to political representation. The constitution requires that seats in Parliament be allocated according to population, with a roughly equal number of voters in each constituency and redistricting carried out after every census. But in 1976 the Congress government froze India’s electoral boundaries for 25 years to avoid penalising states that succeeded with family-planning policies. In 2002 a bjp government extended the moratorium until 2026. The south’s share of India’s population has since dropped by five percentage points, while that of up and Bihar has grown by three points.

The result is a misallocation of seats. Going by the 2011 census, the south should have 18 fewer mps in India’s 545-seat lower house than its current 129. up and Bihar ought to gain 14 over their existing 120, according to calculations by Milan Vaishnav and Jamie Hintson of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, a think-tank in Washington. On average, an mp in Uttar Pradesh represents nearly 3m people; his counterpart in Tamil Nadu a mere 1.8m.

The constitutional and moral arguments in favour of redistricting are plain. But the practical ramifications for southern states would be large. If the centre goes ahead with it, warns a prominent figure in the south, “that is the beginning of the end of India as a country…In my children’s lifetime this will not be one country anymore.” In May Mr Modi inaugurated a new Parliament building, capable of seating 888 lawmakers, lending credence to the idea that his party intends to reallocate seats while also expanding the house in order to soften the blow for states that lose out.

The idea of synchronising India’s many elections is also causing worry. The government’s critics insist that holding all polls at the same time would reinforce the advantages that national parties enjoy over regional ones (such as those that run most of the southern states). Regional parties, which have limited resources, would struggle to fight both national and state-level campaigns at the same time. The bjp counters that the current system, which sees a handful of states go to the polls every year, is broken. It paralyses policymaking, forces political parties into non-stop campaign mode and costs a fortune for parties and the exchequer. Having simultaneous elections would be cheaper and lead to better governance, say supporters.

Analyses of past elections have produced conflicting answers about whether harmonising polls will change how people vote. Any new policy would have to make provisions for state governments losing the support of their legislatures and collapsing in the middle of electoral cycles. And it is unclear whether Mr Modi would be able to push through the constitutional amendments this plan would require.

Since coming to power nine years ago, Mr Modi and his party have fulfilled many elements of their agenda, from turbocharging infrastructure upgrades and raising the country’s global profile to revoking the special constitutional status of the Muslim-majority state of Jammu & Kashmir and building a temple to the Lord Ram in the northern city of Ayodhya. The mystery session of Parliament next week may be about simultaneous elections (an old pledge), about changing India’s name (a newish obsession), or about something else entirely. Whatever the agenda, the great magician must be careful not to saw the nation in half.

India’s Poor Paid for G20 With Homes and Livelihoods Halted

More people will be left homeless and unemployed than before India decided to host the G20 Summit in Delhi.

https://www.newsclick.in/indias-poor-paid-g20-homes-and-livelihoods-halted

The range of distress caused to the poor by the preparations for the G20 summit has been widely reported all year. Since January, over 3 lakh of the capital’s poor have been displaced, while other cities that hosted G20 events reported more evictions and displacements. The lives of India’s poor are jeopardised in the process of urban ‘beautification’ projects meant to please visiting foreign dignitaries and other attendees.

Eighty per cent of Delhi’s workforce is employed in the informal sector, and 15% of its population lives below the poverty line. The city and central administrations, which prepare the capital for summits, have repeatedly behaved with contempt towards its poorest residents. Walls were constructed to hide the city’s poverty and poor residents during the Commonwealth Games in 2020. And in 2023, slums and shelters for the homeless were razed to make way for dazzling optics for the G20 Summit.

The city allocated a expense budget—Rs 1,000 crore—to prepare for this Summit and related events, choosing to chase away the poor rather than work towards poverty reduction. Slum settlements and shelters for the homeless were pulled apart or concealed and demolished with no alternative arrangements made for residents. In effect, more people have been left homeless and unemployed than before India decided to host this event. Homes were declared encroachments and bulldozed, roadside vendors were evicted, and lakhs whose voices are never heard were further destabilised. The brilliant lights of the newly-decorated city darkened lives—and the coming effective ‘shutdown’ of a large and prominent section of the city will worsen the situation.

When a city as large and economically diverse as Delhi is brought to a halt, people are likely to face challenges, significantly more so its weaker and disadvantaged sections. Of the ways in which the poor are affected, the easiest to identify is the loss of daily wages, for instance of the hawkers in parts of the city that are being subjected to near-total lockdown during the forthcoming summit.

While the lockdown may officially apply to sections of the city, roads passing through this crucial area will out of bounds during the days of the G20 programmes. It is bound to affect thoroughfare, having a ripple effect across the city.

Most of Delhi’s poor residents—over 49 lakh people, according to a 2022 estimate—work in the informal sector. They rely on daily wages to support themselves and their families. Any disruption in normal economic activities results in a substantial loss of income, making it difficult for families to meet basic needs. Many poor might find it impossible to stock up on essential food items to provide them with two meals a day when they are forced not to work. This is what leads to food insecurity and hunger for those who live from day to day.

Further, road and office closures can disrupt access to essential services such as healthcare, education, and social support. Vulnerable populations may find it challenging to access medical care or emergency services during this period. Even a short shutdown can have lasting economic consequences for poor individuals and the local economy. Job losses and income reductions during a shutdown can create financial struggles that persist after normal economic activities resume. It’s a fact that today’s food is tomorrow’s work energy: a poor worker who goes hungry today will not have the energy to work tomorrow, perpetuating poverty beyond the days when work was unavailable, and pushing families deeper into poverty.

https://www.wionews.com/world/putin-will-not-attend-g20-in-india-but-set-to-visit-china-for-belt-and-road-forum-630307

Russian President Vladimir Putin will visit China for the Belt and Road Forum in October, Bloomberg reported while citing three people with knowledge of the matter. The visit would be Putin's first since an arrest warrant was issued against the Russian president for alleged war crimes, which the Kremlin has vehemently denied.

Preparations are now underway in Moscow for Putin's visit as Russian President Vladimir Putin has reportedly accepted Chinese leader Xi Jinping's invitation for the top flagship project of his presidency.

That's pretty much it. Vladimir Putin, in a telephonic conversation with India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi on August 28, cited his "busy schedule" and said that his main focus is still the "special military operation" in Ukraine for his inability to attend the G-20 summit in New Delhi in September.

Another facet of the discourse remains that New Delhi has vehemently opposed the G20 summit to emerge as a forum for focus on war in Ukraine, saying that it's a "geo-economic" platform and that the "(UN) Security Council" exists for conflict resolutions.

Putin in the New Delhi G-20 summit would have made him and by extension the war in Ukraine the top focus of a crucial multilateral meeting.

Secondly, Putin is reportedly willing to visit countries where his security service can completely guarantee his safety, and China is one of those places, according to two people cited by Bloomberg.

Kremlin foreign policy aide Yuri Ushakov said in July that Putin planned to visit China for the forum, while Security Council Secretary Nikolai Patrushev said that China had invited the Russian leader as the "main guest" at the event, the state-run TASS news service reported in May.

https://www.wionews.com/world/putin-will-not-attend-g20-in-india-but-set-to-visit-china-for-belt-and-road-forum-630307

Russian President Vladimir Putin will visit China for the Belt and Road Forum in October, Bloomberg reported while citing three people with knowledge of the matter. The visit would be Putin's first since an arrest warrant was issued against the Russian president for alleged war crimes, which the Kremlin has vehemently denied.

Preparations are now underway in Moscow for Putin's visit as Russian President Vladimir Putin has reportedly accepted Chinese leader Xi Jinping's invitation for the top flagship project of his presidency.

That's pretty much it. Vladimir Putin, in a telephonic conversation with India's Prime Minister Narendra Modi on August 28, cited his "busy schedule" and said that his main focus is still the "special military operation" in Ukraine for his inability to attend the G-20 summit in New Delhi in September.

Another facet of the discourse remains that New Delhi has vehemently opposed the G20 summit to emerge as a forum for focus on war in Ukraine, saying that it's a "geo-economic" platform and that the "(UN) Security Council" exists for conflict resolutions.

Putin in the New Delhi G-20 summit would have made him and by extension the war in Ukraine the top focus of a crucial multilateral meeting.

Secondly, Putin is reportedly willing to visit countries where his security service can completely guarantee his safety, and China is one of those places, according to two people cited by Bloomberg.

Kremlin foreign policy aide Yuri Ushakov said in July that Putin planned to visit China for the forum, while Security Council Secretary Nikolai Patrushev said that China had invited the Russian leader as the "main guest" at the event, the state-run TASS news service reported in May.

https://www.wsj.com/world/india/india-keeps-pulling-the-plug-on-its-digital-economy-c320a6b6

Online sellers and ride-hailing drivers count the cost as authorities cut off the internet more than in any other country

When Indian authorities shut down the internet across a remote northeast state in May, Amy Aribam said it wiped out the more than $9,000 in monthly revenue for her home business selling saris online.

Four months later, Aribam is back online but the internet remains down for many, and the women who weave her silk and cotton saris by hand are suffering. “We couldn’t communicate with our customers,” Aribam said. “Our business is completely online.”

Indian authorities said they pulled the plug to stop the spread of rumors as social unrest erupted in Manipur, a state governed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party. India’s government has increasingly shut down the internet to respond to a range of problems, including political upheaval, fugitives on the loose and even cheating on exams.

Nine years after Modi was elected, the world’s most populous democracy leads the world in internet shutdowns, according to tallies by digital-rights groups. Last year’s 84 cutoffs in various parts of the country exceeded the combined total for all other nations, including Iran, Libya and Sudan, New York-based digital rights group Access Now says. Since 2016, when the group began collecting data, India has accounted for more than half of all internet shutdowns globally.

The outages have disrupted the lives of tens of millions of people in a country where inexpensive mobile data and government efforts to facilitate mobile payments have catapulted vast numbers of consumers into the digital age in recent years. About half of India’s 1.4 billion people are now online, increasingly dependent on connectivity to communicate with friends and family, shop online, pay utility bills and more.

Digital-rights advocates say the shutdowns disproportionately affect the poor, often making it harder for them to collect food subsidies and wages through rural employment programs. They also lead to job losses, hamper online transactions and discourage foreign investment. That damps economic growth and disrupts startups and U.S. e-commerce companies, researchers say.

The prime minister’s office and the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Web shutdowns in India between 2019 and 2022 cost more than $4.8 billion in economic activity, according to London-based Top10VPN, which tracks global outages. More than 120 million people in India were affected last year, the group says.

The U.S. has expressed concern even as it increases cooperation with India as a strategic counterweight to China. The State Department said in a March human-rights report that restrictions on internet freedom included authorities’ repeatedly blocking the internet, particularly during periods of political unrest.

In 2015, the year after Modi was elected, he promised to build a “Digital India” connecting the country’s masses. “Digital connectivity should become as much a basic right as access to school,” he said.

https://www.wsj.com/world/india/india-keeps-pulling-the-plug-on-its-digital-economy-c320a6b6

The number of internet users in India has risen to 692 million from 350 million since 2015, according to digital consulting firm Kepios. But government efforts to bolster connectivity are undermined by the government’s shutdowns, said Raman Jit Singh Chima, Asia policy director at Access Now.

“How can you have a ‘Digital India’ with all these shutdowns?” he said.

Among citizens most affected are those who deliver food and groceries or work for ride-hailing services. They typically can’t fulfill orders or pick up passengers without access to their companies’ apps.

Tofeeq Khan, a 32-year-old Uber driver who lives on the outskirts of New Delhi in Haryana state, said he was unable to work for about two weeks last month due to an internet shutdown, imposed during violent clashes between Hindus and Muslims. Authorities said the action was needed to stop the spread of misinformation and to prevent mobs from organizing.

Khan, the sole breadwinner for his parents, wife and two sons, said he lost more than $300 of income, leaving him unable to pay his sons’ school tuition, buy groceries or make payments on his car loan.

“I feel like a mountain of hardships has fallen upon me and my family,” he said. Uber declined to comment.

In March, authorities in the northern state of Punjab, home to more than 27 million people, cut mobile internet and text-messaging services for several days while police sought a Sikh separatist who had called for an independent Sikh homeland. The shutdown was intended to stop his supporters from expressing support online or coordinating escape plans.

In 2021, authorities cut off the internet in Rajasthan state, home to about 80 million people, for up to 12 hours to maintain law and order and prevent what they feared could be cheating on an exam for those seeking coveted jobs as government-school teachers. Copies of exams sometimes spread online before they are administered, and students have been caught using banned devices during exams.

The shutdown response has grown since then, with exam-related outages in several more states, according to the Software Freedom Law Center, India, a group that advocates digital freedom. Last year it filed a public-interest lawsuit, arguing the shutdowns are arbitrary and illegal.

The Muslim-majority region of Kashmir is subject to the most shutdowns. Indian authorities last year cut internet access there 49 times, according to Access Now, more than half of the national total. The restrictions began in 2019 on the grounds that they were needed to maintain public order ahead of New Delhi’s decision to strip the region of its special status. Local businesses say the region’s economy is ailing.

“Earlier the shutdowns were in response to trouble, but now they are being used in preventive ways,” said Namrata Maheshwari, Asia Pacific policy counsel at Access Now.

It is unclear that the blocks assist in ending social upheaval or stop cheating, she said, and they often create anxiety among friends and family who find themselves in the dark, or unable to work.

In Manipur, the internet cuts came during violent clashes between two ethnic groups that killed more than 100 people.

Aribam found an expensive workaround for her sari business. Her brother, with whom she runs the business, flew more than 1,000 miles to New Delhi several times over the months, carrying bags stuffed with the garments. He stayed in a hotel and sold them online using the hotel’s internet connection.

“My family and I can survive during this difficult time because we are privileged in some ways,” she said. “However, the weavers who live hand to mouth are finding it difficult to make ends meet.”

Western countries have for too long acquiesced to the Indian government’s abuses

https://www.economist.com/leaders/2023/09/20/if-india-ordered-a-murder-in-canada-there-must-be-consequences

For years, India objected to Western strategists lumping it together with its violent and chaotic neighbour in the phrase “Indo-Pakistan”. Now recognised as a fast-growing giant and potential bulwark against China, India claims to have been “de-hyphenated”. Yet the explosive charge aired this week by Justin Trudeau suggests that diplomatic recalibration may have gone too far. Canada’s prime minister alleges that Indian agents were involved in the murder in Vancouver of a Canadian citizen sympathetic to India’s Sikh separatist movement. India has long been accused of assassinating militants and dissidents in its own messy region; never previously in the friendly and orderly West. And while India calls the victim, Hardeep Singh Nijjar, a terrorist, he had rebuffed Indian allegations that he was linked to separatist violence.

India denies everything. But Canada is reported to have shared intelligence about the murder with its allies in the “Five Eyes” intelligence pact. None appears to have questioned it. Shortly after Mr Trudeau levelled the charge in Canada’s parliament, America and Britain released cautiously supportive statements, urging India to co-operate with a Canadian probe. The assassination, by two unknown gunmen outside a Sikh temple in June, follows a recent spike in both Sikh separatist activity and at times heavy-handed Indian suppression of it.

The squabble, which has involved tit-for-tat expulsions of Indian and Canadian diplomats, could escalate. Mr Trudeau faces domestic pressure to reveal evidence of Indian involvement in the killing. A criminal investigation is under way. The Canada-India relationship, already blighted by Indian suspicions of separatist support in the 770,000-strong Sikh diaspora in Canada, has grown worse. America and its allies will hope the rot stops there. Yet even if it does, they should consider this a warning-shot against the government of Narendra Modi—and their own eagerness to overlook its too-frequent abuses.

On its own turf it has muzzled the press, cowed the courts and persecuted minorities, even though none is a threat to it. The alleged assassination in Canada, too, appears gratuitous as well as wrong. The movement to create an independent Sikh nation (known as Khalistan) led to the killing of tens of thousands of people in India in the 1980s and 1990s, but has since been not much more than a talking-point in the Sikh diaspora, even as India’s ability to police it by conventional means at home has improved (see Asia section).

Western countries have for too long acquiesced to the Indian government’s abuses

https://www.economist.com/leaders/2023/09/20/if-india-ordered-a-murder-in-canada-there-must-be-consequences

Making martyrs of separatist leaders is a gift to their beleaguered cause. This might be considered typical of an Indian government that, for all its recent swagger on the world stage, remains dogged by feelings of insecurity. It is a feature of India’s rapid rise. The country is almost invariably weaker than its leaders publicly proclaim, yet stronger than they privately fear—and that mismatch is a recipe for miscalculations of this kind. Mr Modi, a probable shoo-in for re-election next year, should know that confident countries entrust their security to the rule of law.

India’s Western friends cannot count on that, however. Hitherto reluctant to condemn Mr Modi’s excesses, they have maintained a fiction that their partnership with India is based on shared democratic values, not interests. This has laid them open to charges of hypocrisy. It also seems likely, in the light of Mr Nijjar’s demise, to have emboldened Mr Modi. If the investigation confirms Indian involvement in this crime, it is time for a tougher line. Strategic partners do not air all their dirty linen in public, but nor do they murder each other’s citizens. Canada’s allies must join it in making that clear to Mr Modi.

@AatishTaseer

So, in retrospect, the G20 was an event where the leaders of Russia and China were not present, while the leader of the free world accused Mr Modi (the host) of extrajudicial murder in Canada. Truly, surreal!

https://x.com/AatishTaseer/status/1706124856843002230?s=20

https://apnews.com/article/india-canada-killing-united-nations-d4e5dbd2acbca4f34ad003f673655eb0

NEW DELHI (AP) — The Group of 20 Summit, hosted by India earlier this month, couldn’t have gone better for Prime Minister Narendra Modi. His pledge to make the African Union a permanent member became reality. And under his leadership, the fractured grouping signed off on a final statement. It was seen as a foreign policy triumph for Modi and set the tone for India as a great emerging power.

Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar was expected to seize on India’s geopolitical high in his speech at the United Nations on Tuesday. But circumstances have changed — quite abruptly — and India comes to the General Assembly podium with a diplomatic mess on its hands.

On Monday, Canadian leader Justin Trudeau made a shocking claim: India may have been involved in the killing of a Sikh Canadian citizen in a Vancouver suburb in June.

Trudeau said there were “credible allegations” of links to New Delhi, which India angrily rejected as absurd. It has been a free fall since: Each expelled a diplomat, India suspended visas for Canadians, and Ottawa said it may reduce consulate staff over safety concerns. Ties between the two once-close countries have sunk to their lowest point in years.

“In the immediate term, this will bring New Delhi back down to Earth. It has a crisis that it needs to work through, quickly but carefully,” said Michael Kugelman, director of the Wilson Center’s South Asia Institute.

TENSIONS WERE ALREADY SIMMERING

On the last day of the G20 summit, Trudeau posed and smiled with Modi as world leaders paid respects at Mahatma Gandhi’s memorial. Behind the scenes though, tensions were high.

Trudeau skipped an official dinner hosted by the Indian president, and local media reported he was snubbed by Modi when he got a quick “pull aside” instead of a bilateral meeting. To make things worse, a flight snag saw him stranded in New Delhi for 36 hours. Finally back in Canada, Trudeau said he had raised the allegations with Modi at the G20.

As India heads to the United Nations, the allegations have “thrown cold water on India’s G20 achievements,” said Happymon Jacob, founder of the New Delhi-based Council for Strategic and Defense Research.

India has long sought greater recognition at the United Nations. For decades, it has eyed a permanent seat at the Security Council, one of the world’s most prestigious high tables. But it has also been critical of the global forum, partly because it wants more representation that’s in line with its rising soft power.

“The U.N. Security Council, which is the core of the United Nations system, is a family photo of the victors of the Second World War plus China,” Jacob said. India believes “it simply does not reflect the demographic, economic and geopolitical realities of today,” he added. Others in the elite group include France, Russia, Britain and the United States.

In April, Jaishankar said India, the world’s most populous country with the fastest growing economy among major nations, couldn’t be ignored for too long. The U.N. Security Council, he said, “will be compelled to provide permanent membership.”

The United States, Britain and India’s Cold War-era ally Russia have voiced support for its permanent membership over the years. But U.N. bureaucracy has stopped the council from expanding. And even if that changes, China — India’s neighbor and regional rival — would likely block a request.

INSTEAD OF THE UN, INDIA MAKES SOME END RUNS

Kept out of the U.N.’s most important body, Modi has made sure that his country is smack at the center of a tangled web of global politics. On one hand, New Delhi is part of the Quad and the G20, seen as mostly Western groups. On the other, it wants to expand its influence in the BRICS and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, where Russia and China dominate.

The deft juggling of the West and the rest has come to define India’s multipolar foreign policy.

https://apnews.com/article/india-canada-killing-united-nations-d4e5dbd2acbca4f34ad003f673655eb0

Its diplomatic sway has only grown over its reluctance to condemn Russia for its war in Ukraine, a stance that resonated among many developing countries that have also been neutral. And the West, which sees an ascendant India as crucial to countering China, has stepped up ties with Modi. By doing so, it looks past concerns of democratic backsliding under his government.

In the immediate aftermath, the first reaction from Canada’s Western allies — including its biggest one, the United States — was tepid. But as the row deepens, the question likely worrying Indian officials is this: Will the recent international fiasco jeopardize its surging ties with the West?

After an initial muted response, the White House has intensified its concerns. “There’s not some special exemption you get for actions like this, regardless of the country,” security adviser Jake Sullivan said. On Friday, Secretary of State Antony Blinken said the U.S. was deeply concerned about the allegations and that “it would be important that India work with the Canadians on this investigation.”

While there’s been no public evidence, a Canadian official told The Associated Press that the allegation of India’s involvement in the killing of Hardeep Singh Nijjar, a Sikh separatist, is based on surveillance of Indian diplomats in Canada — including intelligence provided by a major ally. On Friday, the U.S. ambassador to Canada confirmed this, saying information shared by the intelligence-sharing ‘Five Eyes’ alliance helped link India to the assassination.

At the United Nations, where he held a news conference and meetings but will not be speaking for his nation on Tuesday, Trudeau told reporters that he doesn’t want to cause problems but said his decision was not made lightly. Canada, he said, had to stand up for the rule of law and protect its citizens.

For New Delhi, the U.N. meeting may present a possible opportunity. Indian and Canadian diplomats could meet on the sidelines to try to lower temperatures with a potential assist from Washington, Kugelman said. Canada’s delegation chair, Robert Rae, is delivering the country’s remarks 10 spots after India.

By Chietigj Bajpaee

https://thediplomat.com/2023/10/the-israel-palestine-conflagration-is-a-cautionary-tale-for-indias-global-ambitions/

the most recent developments in the Middle East show how unresolved disputes have a tendency to flare up. In this context, tensions with Pakistan (and to a lesser extent China) remain a constant thorn in India’s global ambitions.

--------------

Claims of a “new Middle East” have been quashed as the “old Middle East” has returned with a vengeance: The devastating October 7 Hamas terrorist attacks on Israel have been followed by unprecedented Israeli attacks on Gaza and the resumption of prolonged Israel-Palestine hostilities. This has also called into question the future of diplomatic initiatives such as the Abraham Accords, which normalized relations between Israel and several Arab states, the Saudi-Iran resumption of diplomatic relations earlier this year, and efforts to facilitate a rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Israel.

What does this mean for India? Beyond the Modi government’s unequivocal support for Israel (which is arguably more equivocal at the level of public opinion, given India’s longstanding support for the Palestinian cause) the latest hostilities in the Middle East hold lessons for India’s global ambitions.

Recent years have seen India raise its voice on the world stage. India’s G-20 presidency strengthened the country’s credentials as the voice of the Global South. New Delhi is offering Indian solutions to global problems, ranging from climate change and sustainability to digital public infrastructure and global health. India has spearheaded new connectivity initiatives, from its rebranded “Act East” Policy in the East to the India-Middle East-Economic Corridor and I2U2 (India-Israel-UAE-U.S.) grouping in the West.

Despite the growing polarization of the international system following the Russian invasion of Ukraine, India has been courted by all major poles of influence. It is a member of both Western-led initiatives such as the Quad and non-Western initiatives such as the BRICS and Shanghai Cooperation Organization.

Undergirding these developments are India’s impressive achievements, ranging from its space program marking a global first to surpassing the United Kingdom in GDP and surpassing China in population. Projections China in population. Projections hold that India will be the world’s fastest growing major economy in 2023; it is on course to surpass Germany and Japan to emerge as the world’s third-largest economy by the end of this decade. Meanwhile, the Indian government has just announced that it will submit a bid to host the 2036 Olympic games.

But the most recent developments in the Middle East show how unresolved disputes have a tendency to flare up. In this context, tensions with Pakistan (and to a lesser extent China) remain a constant thorn in India’s global ambitions.

All it would take is another high-profile terrorist attack on India, followed by the mobilization of both countries’ militaries, to erode investor confidence. This would undermine India’s ambitions to emerge as an engine of global growth, a global manufacturing hub and a beneficiary of the push to de-risk or decouple supply chains away from China. It would also challenge the government’s credentials as the “chowkidar” or watchman/protector of India’s interests, just as Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s “Mr. Security” reputation has been tarnished by the recent Hamas attacks. As such, despite India’s success in de-hyphenating its relationship with Pakistan, the unresolved Kashmir dispute and relations with Pakistan remain a key challenge to India’s global ambitions.

https://theprint.in/diplomacy/pakistan-beats-india-38-18-at-unesco-vote-global-south-may-have-sided-with-it/1867290/

Islamabad's candidate secured the post of vice-chairperson of the UNESCO executive board. India’s defeat contravenes decades of its diplomatic policy approach to such elections.

KESHAV PADMANABHAN

New Delhi: Pakistan beat India with more than double the votes to secure the post of vice-chair of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) executive board last week. While 38 members of the 58-member executive board voted for Islamabad’s candidate, only 18 voted for New Delhi’s representative, and two countries abstained.

The executive board is one of the three constitutional organs of UNESCO — a specialised agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, sciences, culture, communication and information. The other two are the general conference and the secretariat.

India was elected to the UNESCO executive board in 2021 for a four-year term till 2025. Pakistan was elected earlier this year for a four-year term that will end in 2027.

India’s defeat in this vote contravenes decades of its diplomatic policy approach to such elections. “India’s policy has always been to stand in elections that are winnable. If the election is deemed risky, then full efforts are made to ensure India’s victory,” an individual familiar with the matter told ThePrint.

This also comes at a time when India has been projecting itself as the ‘voice’ of the ‘Global South’ — a term used to refer to low- and middle-income countries located in the Southern Hemisphere, mainly in Africa, Asia and Latin America. While the election was held by secret ballot, that India received only 18 votes suggests that these ‘Global South’ countries may have largely sided with Pakistan, since they form the majority of the board members.

The bureau of the executive board consists of 12 members — the chairperson, six vice-chairpersons and the five chairpersons of the permanent commissions and committees. The key roles played by the bureau include setting the agenda and allocating time for executive board meetings. The vice-chairperson has no decision-making powers.

All members of UNESCO are grouped into six regional electoral groups, and each such group is represented by a vice-chairperson. This latest election won by Pakistan was for the vice-chairperson of Group IV, which includes Australia, Bangladesh, China, Cook Islands, India, Indonesia, Japan, the Philippines, Republic of Korea, Sri Lanka and Vietnam.

On 24 November, the spokesperson for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Pakistan had posted on X, stating that Islamabad was elected as vice-chairperson with “overwhelming support”.

India’s permanent representative to the UNESCO is a political appointee, Vishal V. Sharma, a former independent director of Bharat Petroleum Corporation Limited (BPCL) as well as former officer on special duty to Narendra Modi when he was Gujarat chief minister.