India Tops South Asia Hunger Chart Amid COVID19 Pandemic

India ranks 94th among 107 nations ranked by World Hunger Index in 2020. Other South Asian have fared better: Pakistan (88), Nepal (73), Bangladesh (75), Sri Lanka (64) and Myanmar (78) – and only Afghanistan has fared worse at 99th place. The COVID19 pandemic has worsened India's hunger and malnutrition. Tens of thousands of Indian children were forced to go to sleep on an empty stomach as the daily wage workers lost their livelihood and Prime Minister Narendra Modi imposed one of the strictest lockdowns in the South Asian nation. Pakistan's Prime Minister Imran Khan opted for "smart lockdown" that reduced the impact on daily wage earners. China, the place where COVID19 virus first emerged, is among 17 countries with the lowest level of hunger.

|

| World Hunger Rankings 2020. Source: World Hunger Index Report |

Hunger and malnutrition are worsening in parts of sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia because of the coronavirus pandemic, especially in low-income communities or those already stricken by continued conflict.

|

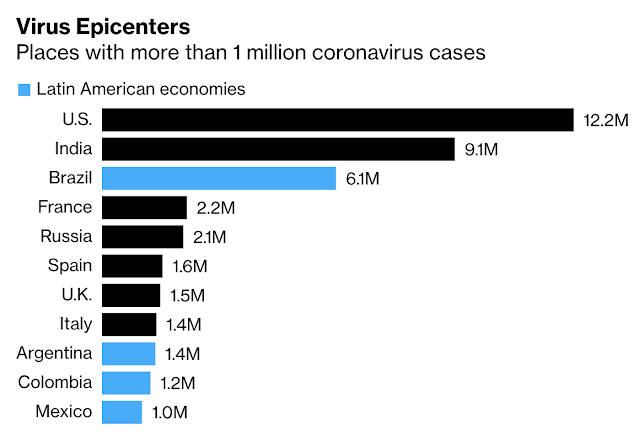

| Global Epicenters of Covid19. Source: Bloomberg |

Global food prices are soaring by double digits amid the coronavirus pandemic, according to Bloomberg News. Bloomberg Agriculture Subindex, a measure of key farm goods futures contracts, is up almost 20% since June. It may in part be driven by speculators in the commodities markets. These rapid price rises are hitting the people in Pakistan and the rest of the world hard. In spite of these hikes, Pakistan remains among the least expensive places for food, according recent studies. It is important for Pakistan's federal and provincial governments to rise up to the challenge and relieve the pain inflicted on the average Pakistani consumer.

|

| Global Agricultural Futures Contracts. Source: Bloomberg |

Global Food Prices:

Global food prices are increasing at least partly due to several nations buying basic food commodities to boost their strategic reserves in the midst of the pandemic. A Bloomberg News report says that "agricultural commodity buyers from Cairo to Islamabad have been on a shopping spree since the Covid-19 pandemic upended supply chains". It may in part be driven by speculators in the commodities markets. Here's an excerpt of the Bloomberg story:

"Agricultural prices have been on the rise as countries stepped up purchases, adding to demand from China and a drought in the Black Sea region. That has helped push the Bloomberg Agriculture Subindex, which measures key farm goods futures contracts, up almost 20% since June. Sugar prices have gained a boost as China replenished stockpiles, said Geovane Consul, chief executive officer of a Brazilian sugar and ethanol joint venture between U.S. agribusiness giant Bunge Ltd. and British oil major BP Plc."

Supply Constraint in Pakistan:

The Pakistan Government estimates final wheat production ended up at 25.5 million tons, slightly above the five-year average of 25.38 million tons, according to Grain Central. While that represented a 1.2 million tons increase on the 24.3 million tons harvested in 2019, it was well short of the government’s target of 27 million tons, forcing Pakistan to import wheat at higher global prices.

Demand for fruits and vegetables is also rising at about 9.5% a year, according to Mordor Intelligence. The supply is falling short of demand, putting pressure on prices.

|

| Global Food Price Comparison. Source: Bayut |

The food prices have risen 14% for urban and 16.8% for rural areas of Pakistan in the last 12 months, according to Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. In spite of this inflationary trend, the grocery prices in Pakistan remain among the lowest in the world. A comparison by Dubai-based Bayut shows that groceries in Pakistan cost 72.9% less than in the United States. Other least-expensive countries for groceries include Tunisia ( 67% less), Ukraine ( 66.7% less), Egypt (65.6% less) and Kosovo (65.6% less).

Globally, Switzerland sells the most expensive groceries, with prices 79.1% higher than in the U.S. Norway is the second most expensive place to buy groceries, with prices 37.4% more expensive than in the U.S., and Iceland is third most expensive, where food items are 36.6% pricier, according to Bayut.

|

| Cost of Dining Out. Source: Commodity.com |

Summary:

India ranks 94th among 107 nations ranked by World Hunger Index in 2020. China, the place where COVID19 virus first emerged, is among 17 countries with the lowest level of hunger. Other South Asian have fared better: Pakistan (88), Nepal (73), Bangladesh (75), Sri Lanka (64) and Myanmar (78) – and only Afghanistan has fared worse at 99th place. However, global food price hikes have also hit average Pakistani hard in spite of the fact that grocery prices in Pakistan remain the lowest the world. Bloomberg Agriculture Subindex, a measure of key farm goods futures contracts, is up almost 20% since June. It may in part be driven by speculators in the commodities markets. World food commodity prices are increasing at least partly due to several nations buying basic food commodities to boost their strategic reserves in the midst of the pandemic. It is important for Pakistan's federal and provincial governments to intervene in the markets to relieve the average Pakistani consumer's pain.

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

South Asia Investor Review

COVID19 in Pakistan: Test Positivity Rate and Deaths Declining

Construction Industry in Pakistan

Pakistan's Pharma Industry Among World's Fastest Growing

Pakistan to Become World's 6th Largest Cement Producer by 2030

Is Pakistan's Response to COVID19 Flawed?

Pakistan's Computer Services Exports Jump 26% Amid COVID19 Lockdown

Coronavirus, Lives and Livelihoods in Pakistan

Vast Majority of Pakistanis Support Imran Khan's Handling of Covid19 Crisis

Pakistani-American Woman Featured in Netflix Documentary "Pandemic"

Coronavirus Antibodies Testing in Pakistan

Can Pakistan Effectively Respond to Coronavirus Outbreak?

How Grim is Pakistan's Social Sector Progress?

Pakistan Fares Marginally Better Than India On Disease Burdens

Trump Picks Muslim-American to Lead Vaccine Effort

Democracy vs Dictatorship in Pakistan

Pakistan Child Health Indicators

Pakistan's Balance of Payments Crisis

Panama Leaks in Pakistan

Conspiracy Theories About Pakistan Elections"

PTI Triumphs Over Corrupt Dynastic Political Parties

Strikingly Similar Narratives of Donald Trump and Nawaz Sharif

Nawaz Sharif's Report Card

Riaz Haq's Youtube Channel

Comments

"China, which embarked on the mission of becoming a superpower by showing its economic and military might to the world, now may be brought to its knees over a shortage of food. Reduction in overall domestic food production; a recent deluge in the Yangtze River basin, the rice bowl of China; and a slash in imports, mostly aggravated by deteriorating diplomatic relations, has caused Beijing to hit the panic button"

https://thehill.com/opinion/international/516607-another-famine-coming-china-struggles-to-meet-basic-food-demands

A number of countries, including China, are stockpiling for an uncertain pandemic season amid concerns over whether the global supply chain for food can remain intact as COVID-19 cases rise worldwide.

World food prices have been rising for four straight months, according to a United Nations price index. Countries importing grains to boost their pandemic stockpiles include Egypt, Jordan, Taiwan and others.

“China comes to mind, as they’ve taken on a massive restocking program,” said Michael Magdovitz, food and agriculture analyst at Rabobank. “But also India. Countries may increase their buffers to avoid any supply-side issues,” such as lockdowns or border closures should the pandemic worsen.

“I think people are trying to protect their own interests, which in some ways is rational,” Preston said. “Even if it can cause what they call a ‘commons problem,’ where then there’s not enough for everybody.”

When the pandemic first hit, governments and food security authorities expressed concerns about food protectionism. That didn’t come to pass globally.

Still, bottlenecks have turned up in developing countries. In South Africa, workers were banned from traveling to a packing plant for citrus, said Thomas Reardon, agricultural economist at Michigan State University.

“Also, because wood was not classed as an essential item, the wood was not coming in to make packing crates, so the fruit could not be packed,” Reardon said.

Globally, the prices of grain and meat continue to rise, just as more and more people can’t afford them given widespread job losses. Sherman Robinson, trade scholar at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, said food insecurity is showing up everywhere.

“It’s widespread across developing countries,” Robinson said. “In the developed countries, it really depends on how good your social safety net is. So in the U.S. case, we’re probably among the worst of the developed countries.”

OXFAM #Inequality Index: #India's #Health Budget Is 4th Lowest In The World; Worse Than #Pakistan, #Nepal Amidst #COVID19 #Pandemic. @trakintech https://trak.in/tags/business/2020/10/13/shocking-indias-health-budget-is-4th-lowest-in-the-world-worse-than-pakistan-nepal/

https://www.oxfam.org/en/research/fighting-inequality-time-covid-19-commitment-reducing-inequality-index-2020

According to the latest ‘Commitment to Reducing Inequality Index 2020’, report published by the international charity confederation Oxfam on

7 October 2020 , India ranked 155th in a survey consisting of 158 countries, showing that the country spends less than 4% of its budget on health.

The health spending index of India is so poor that even its neighbouring countries like Pakistan, Nepal and Bangladesh spend slightly more than 4% of their budget on health.

As per Oxfam’s latest 2020 Index report, of the 158 countries surveyed for checking whether they allocate 15% of their respective budgets on health as recommended, it was found that Nigeria, Bahrain and India were among the lowest rankers, in terms of health spending index.

India secured the 155th spot, sharing its position with Afghanistan, both of which allocated less than 4% of their budget on health.

Speaking of health spending indices, Oxham found that only 28 of these 158 surveyed countries were spending the recommended fraction of 15% of their budgets on health.

The report said, “India’s health budget is the fourth lowest in the world. Just half of its population have access to even the most essential health services”.

The report also mentioned that while the trend of allocating a very small percentage of budget towards health is persistent across South Asian countries,

Pakistan spent a little over 4% of its budget on health, while

Nepal and Bangladesh spent 5%.

The report reads,

“This is particularly damaging when just half of India’s population (55%) has access to even the most essential services, and more than 70% of health spending is being met from household budgets.”

Also, as per the database from the World Bank, in 2017 India dedicated only 3.4% of its expenditure towards health.

Just to get an understanding of comparison, in the same year Japan spent 23.6% of the government budget on health.

A global ranking of governments based on what they are doing to tackle the gap between rich and poor

http://www.inequalityindex.org/

The Overall Index Score combines all three core pillars on which the index is based: social spending, progressive taxation policies and labour rights.

Pakistan ranks 128 among 158 countries. India ranks 129 & Bangladesh 113.

https://twitter.com/haqsmusings/status/1317991276583636993?s=20

Ever since it began opening up the economy in the 1990s, India’s dream has been to emulate China’s rapid expansion. After three decades of persevering with that campaign, slipping behind Bangladesh hurts its global image. The West wants a meaningful counterweight to China, but that partnership will be predicated on India not getting stuck in a lower-middle-income trap.

------------

Consider first the exceptionalism of India’s growth. Bangladesh is doing well because it’s following the path of previous Asian tigers. Its slice of low-skilled goods exports is in line with its share of poor-country working-age population. Vietnam is punching slightly above its weight. But basically, both are taking a leaf out of China’s playbook. The People’s Republic held on to high GDP growth for decades by carving out for itself a far bigger dominance of low-skilled goods manufacturing than warranted by the size of its labor pool.

India, however, has gone the other way, choosing not to produce the things that could have absorbed its working-age population of 1 billion into factory jobs. “India’s missing production in the key low-skill textiles and clothing sector amounts to $140 billion, which is about 5% of India’s GDP,” the authors say.

If half of India’s computer software exports in 2019 ceased to exist, there would be a furor. But that $60 billion loss would have been the same as the foregone exports annually from low-skill production. It’s real, and yet nobody wants to talk about it. Policymakers don’t want to acknowledge that the shoes and apparel factories that were never born — or were forced to close down — could also have earned dollars and created mass employment. They would have provided a pathway for permanent rural-to-urban migration in a way that jobs that require higher levels of education and training never can. Bangladesh has two out of five women of working age in the labor force, double India’s 21% participation rate.

The elite in New Delhi delude themselves by thinking the country can hold its own on the world stage

By BHIM BHURTEL

OCTOBER 20, 2020

Despite Indian strategists’ claim that India is an aspirant global power, it is at the bottom in South Asia except for war-torn Afghanistan in the GHI ranking.

The report suggests that India ranks 94th out of 104 countries listed. India shares the same rank as Sudan, in the red zone. That means India’s hunger situation is in the “alarming” category. India’s South Asian peers rank as follows: Sri Lanka 64, Nepal 73, Bangladesh 75, and Pakistan 88.

---------

The perceptions of Indian political leaders and top bureaucrats about their country’s position in the world appear far removed from reality.

These elites appear not to be mindful of the republic’s fundamental purposes envisaged in the constitution. And they seem lost to their duty and function to the people.

Yet they want to attempt a massive task that is beyond their economic, technological, political, military and strategic capacity.

----------

India is unable to feed its kids and yet dreams of being a global strategic player.

Second, I read a report by Andy Mukherjee in Bloomberg Business dated October 17. The headline is fascinating: “The next China? India must first beat Bangladesh.”

Mukherjee writes: “Ever since it began opening up the economy in the 1990s, India’s dream has been to emulate China’s rapid expansion. After three decades of persevering with that campaign, slipping behind Bangladesh hurts its global image. The West wants a meaningful counterweight to China, but that partnership will be predicated on India not getting stuck in a lower-middle-income trap.”

The third report I skimmed was published earlier but is still relevant. The Davos-based World Economic Forum (WEF) started to publish the World Inclusive Development Report (IDI) in 2017.

The WEF says IDI is designed as an alternative to GDP and reflects more closely the criteria by which people evaluate their countries’ economic progress. The IDI 2018 ranking suggested that India is again at the bottom. In the IDI ranking of 74 states in the Emerging Economies category, Nepal ranks No 22, Bangladesh 34, Sri Lanka 40, Pakistan 47, and India 62.

Besides, India, the world’s largest functional democracy, is not a role model for other countries in South Asia, even for its human-rights record. Amnesty International’s recent closure of its operations in India confirms this.

These reports show that India is neither comparable to the traditional superpower, the US, nor to an emerging superpower, China. It is also not equal to a middle-power country like Japan or Germany. It is not even equivalent to its immediate neighbors Bangladesh, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Nepal in many development indicators.

India lags its South Asian peers. Therefore, India is not a role model in the South Asia region, either in economic performance or in socioeconomic development. Recently, South Asian countries have been looking to China with hope rather than India because of India’s poor image. A country with a lower socioeconomic development ranking cannot be a role model for higher-ranked countries.

Indian leaders’ and bureaucrats’ denials won’t work for India. The sooner India accepts that it lags far behind superpowers, middle-power countries and its immediate neighbors, the sooner it will start fixing its economy.

Hubris of being a global player may be useful for Indian leaders and officials but it won’t help the people.

One evening in August, a 14-year-old boy snuck out of his home and boarded a private bus to travel from his village in Bihar to Jaipur, a chaotic, crowded and historical city 800 miles away in India's Rajasthan state.

He and his friends had been given 500 rupees (about $7) by a man in their village to "go on vacation" in Jaipur, said the boy, who CNN is calling Mujeeb because Indian law forbids naming suspected victims of child trafficking.

As the bus entered Jaipur, it was intercepted by police.

The man was arrested and charged under India's child trafficking laws, along with two other suspects. Nineteen children, including Mujeeb, were rescued. Jaipur police said they were likely being taken to bangle factories to be sold as cheap labor.

In India, children are allowed to work from the age of 14, but only in family-related businesses and never in hazardous conditions. But the country's economy has been hit hard by the coronavirus pandemic and many have lost their jobs, leading some families to allow their children to work to bring in anything they can.

Making colored lac bangles like those sold in Jaipur is hot and dangerous work, requiring the manipulation of lacquer melted over burning coal. Bangle manufacturing is on the list of industries that aren't allowed to employ children under 18.

"Children have never faced such crisis," said 2014 Nobel Peace Prize winner Kailash Satyarthi, whose organization Bachpan Bachao Andolan (Save the Childhood Movement) works to protect vulnerable children. "This is not simply the health crisis or economic crisis. This is the crisis of justice, of humanity, of childhood, of the future of an entire generation."

When India went into a strict lockdown in March, schools and workplaces closed. Millions of children were deprived of the midday meal they used to receive at school and many people lost their jobs.

Traffickers have exploited the situation by targeting desperate families, activists said.

Between April and September, 1,127 children suspected of being trafficked were rescued across India and 86 alleged traffickers were arrested, according to Bachpan Bachao Andolan.

Most of the children came from rural areas of poorer states, such as Jharkhand or Bihar. Pramila Kumari, the chairwoman of Bihar's Commission For Protection Of Child Rights, said the government commission had received more complaints of trafficking during the pandemic.

Child trafficking, when young people are tricked, forced or persuaded to leave their homes and then exploited, forced to work or sold, can occur in several ways. Experts say sometimes, children are lured with false promises without their parents ever knowing, like Mujeeb. Other times, desperate parents hand their children over to work so they can send money home.

Latest estimate from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) reports - World Economic Outlook: A Long and Difficult Ascent, October 2020 and Fiscal Monitor: Policies for the Recovery, October 2020- shows that 90 million people globally would slip into "extreme poverty" (surviving on $1.9 a day) due to the pandemic. This is in line with the World Bank's June 2020 estimate ("Projected poverty impacts of COVID-19") which estimated 70-100 million to slip into extreme poverty.

-------------

Earlier this month, the Global Hunger Index 2020 report ranked India at 94 (of 107 it mapped for the 2020 report), far below neighbouring Sri Lanka, Bangladesh and Pakistan. This index is based on four component indicators: (i) undernourishment (insufficient caloric intake) (ii) child wasting (under 5 years) (iii) child stunting (under 5 years) and (iv) child mortality (under 5 years).

India's progress has been very tardy compared to its neighbours as the following graph shows. Its "child wasting" (low weight for age reflecting acute undernourishment) and "child stunting" (low weight for age reflecting chronic under-nutrition) is particularly poor. The hunger index scores are measured on a scale of 0-100, where '0' represents zero hunger.

---------------------

The inept and callous handling of the pandemic and the untimely and unplanned lockdown has jolted India like no other country. Its GDP growth for the April-June 2020 quarter tanked to minus 23.9% - the highest among major economies. The RBI estimates the GDP growth for the entire fiscal to be minus 9.5%, as against the IMF's estimate of minus 10.3%, while its global average is estimated to be minus 4%. (To know why read "Rebooting Economy 37: Do high-frequency data suggest V-shaped recovery? ")

Also Read: Rebooting Economy VIII: COVID-19 pandemic could push millions of Indians into poverty and hunger

India would account for 40 million of the 90 million the IMF says would turn extremely poor or 44.4% of all. The following graph from the IMF's Fiscal Monitor report shows that in India (extreme left), their number would rise from 80 million in 2018 to 120 million in 2020.

https://www.businesstoday.in/opinion/columns/indian-economy-coronavirus-impact-indias-growing-poverty-and-hunger-due-to-covid19-pandemic-effect/story/420575.html

https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WEO/Issues/2020/09/30/world-economic-outlook-october-2020

India’s economy shrank 7.5% last quarter on top 24% decline in previous quarter. #Modi #BJP #Hindutva |The New York Times https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/27/business/economy/india-economy-covid-19.html

“India was expected to really step into China’s shoes and give that additional boost to globalization that was missing,” said Priyanka Kishore, head of South Asia at Oxford Economics. “And that’s where India didn’t really play out the role it was largely expected to play, and that role seems to be diminishing more and more.”

------------------

An estimated 140 million people lost their jobs after India locked down its economy in March to stop the outbreak, while many others saw their salaries drastically reduced, the Mumbai-based Center for Monitoring Indian Economy said. As the lockdown was eased, many went back to work, but more than six million people who lost jobs haven’t found new employment.

In a June survey by the All India Manufacturers Organization, about one-third of small and medium-sized enterprises indicated that their businesses were beyond saving. The industry group said that such a “mass destruction of business” was unprecedented.

-------

Just a few years ago, India, with a population of 1.3 billion people, was one of the world’s fastest-growing large economies. It regularly clocked growth of 8 percent or more.

Global businesses began to warm to the idea of India as a potential substitute to China, both as a place to make goods and to sell them. China’s costs are rising, and its trade war with the United States has complicated doing business there. The Chinese Communist Party is increasingly intruding into business matters, and local Chinese competitors have upped their game against international brands.

But India’s economy was facing headwinds well before the pandemic. Between April and December 2019, G.D.P. grew only 4.6 percent.

-------

One of Mr. Modi’s policies, called demonetization, banned large currency notes overnight in an effort to crack down on tax avoidance and money laundering. Under another, India replaced its welter of national and state taxes with a single value-added tax, in part to cut down on corruption among tax collectors.

Mr. Modi also increasingly turned India’s industrial policy inward, which many economists say has hurt overall growth. The country has long nurtured some of the steepest trade barriers of any major economy, to help its domestic industries develop. Mr. Modi added to that in areas like electronics. His government has also tightened rules around e-commerce, to assist Indian businesses that compete with companies like Amazon and Wal-Mart.

“The slowdown,” said Ms. Kishore, “is almost homegrown.”

India has slipped to the 101st position among 116 countries in the Global Hunger Index (GHI) 2021 from its 2020 ranking (94), to be placed behind Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal.

With this, only 15 countries — Papua New Guinea (102), Afghanistan (103), Nigeria (103), Congo (105), Mozambique (106), Sierra Leone (106), Timor-Leste (108), Haiti (109), Liberia (110), Madagascar (111), Democratic Republic of Congo (112), Chad (113), Central African Republic (114), Yemen (115) and Somalia (116) — fared worse than India this year.

A total of 18 countries, including China, Kuwait and Brazil, shared the top rank with GHI score of less than five, the GHI website that tracks hunger and malnutrition across countries said on Thursday.

The report, prepared jointly by Irish aid agency Concern Worldwide and German organisation Welt Hunger Hilfe, mentioned the level of hunger in India as “alarming” with its GHI score decelerating from 38.8 in 2000 to the range of 28.8 – 27.5 between 2012 and 2021.

The GHI score is calculated on four indicators — undernourishment; child wasting (the share of children under the age of five who have low weight for their height, reflecting acute undernutrition); child stunting (children under the age of five who have low height for their age, reflecting chronic undernutrition); child mortality (the mortality rate of children under the age of five).

According to the report, the share of wasting among children in India rose from 17.1 per cent between 1998-2002 to 17.3 per cent between 2016-2020, “People have been severely hit by COVID-19 and by pandemic related restrictions in India, the country with highest child wasting rate worldwide,” the report said.

Neighbouring countries like Nepal (76), Bangladesh (76), Myanmar (71) and Pakistan (92), which are still ahead of India at feeding its citizens, are also in the ‘alarming’ hunger category.

However, India has shown improvement in indicators like the under-5 mortality rate, prevalence of stunting among children and prevalence of undernourishment owing to inadequate food, the report said.

Stating that the fight against hunger is dangerously off track, the report said based on the current GHI projections, the world as a whole — and 47 countries in particular — will fail to achieve even a low level of hunger by 2030.

“Although GHI scores show that global hunger has been on the decline since 2000, progress is slowing. While the GHI score for the world fell 4.7 points, from 25.1 to 20.4, between 2006 and 2012, it has fallen just 2.5 points since 2012. After decades of decline, the global prevalence of undernourishment — one of the four indicators used to calculate GHI scores — is increasing. This shift may be a harbinger of reversals in other measures of hunger,” the report said.

Food security is under assault on multiple fronts, the report said, adding that worsening conflict, weather extremes associated with global climate change, and the economic and health challenges associated with Covid-19 are all driving hunger.

“Inequality — between regions, countries, districts, and communities — is pervasive and, (if) left unchecked, will keep the world from achieving the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) mandate to “leave no one behind,” it said.

2000 India 38.8 Pakistan 36.7

2008 India 37.4 Pakistan 33.1

2012 India 28.8 Pakistan 32.1

2020 India 27.2 Pakistan 24.6

2021 India 27.5 Pakistan 24.7

https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/2021%20GHI%20Synopsis%20EN.pdf

Prime Minister Narendra Modi while addressing the event of the launch of seven state-run defence companies on the occasion of Vijaydashmi, said that he wants to robust India's defence capabilities in an 'Aatmnirbhar' way.

On the occasion of Vijaydashmi, Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched seven state run defence companies.

The government passed an order on 16th June to convert Ordnance Factory Board from a Government Department into seven 100% Government owned corporate entities.

The Prime Minster said, "India is taking new resolutions to build new future. Today, there is more transparency & trust in defence sector than ever before."

Stressing on the need for aatmnirbhar bharat, he said, "Under the aatmnirbhar bharat scheme, our goal is to make country world's biggest military power on its own.

He said that major reforms have been rolled out in defence sector; instead of the conventional stagnant policies, the single window system has been arranged now.

"After Independence, there was a need to upgrade ordnance factories, adopt new-age technologies, but it didn't get much attention," the Prime Minister said.

The Prime Minsiter's office informed that the new strategy for defence production will focus on, 'Import substitution, diversification, newer opportunities and exports'.

Defence Minister Rajnath Singh and representatives from the defence industry associations were present in the event.

The Government of India has decided to convert Ordnance Factory Board from a Government Department into seven 100% Government owned corporate entities, as a measure to improve 'self-reliance in the defence preparedness of the country'. This move will bring about enhanced functional autonomy, efficiency and will unleash new growth potential and innovation, the Prime Minister's Office released a video informing about it.

Rs. 65,000 Crore have been moved from the Ordinance Factory Board and allotted to these 7 companies, the video added.

New Delhi, October 19

India is ranked at 71st position in the Global Food Security (GFS) Index 2021 of 113 countries, but the country lags behind its neighbours Pakistan and Sri Lanka in terms food affordability, according to a report.

Pakistan (with 52.6 points) scored better than India (50.2 points) in the category of food affordability. Sri Lanka was even better with 62.9 points in this category on the GFS Index 2021, a global report released by Economist Impact and Corteva Agriscience on Tuesday said.

Ireland, Australia, the UK, Finland, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Canada, Japan, France and the US shared the top rank with the overall GFS score in the range of 77.8 and 80 points on the index.

The GFS Index was designed and constructed by London-based Economist Impact and is sponsored by Corteva Agriscience.

The GFS Index measures the underlying drivers of food security in 113 countries, based on the factors of affordability, availability, quality and safety, and natural resources and resilience. It considers 58 unique food security indicators including income and economic inequality – calling attention to systemic gaps and actions needed to accelerate progress toward United Nations Sustainable Development Goal of Zero Hunger by 2030.

According to the report, India held 71st position with an overall score of 57.2 points on the GFS Index 2021 of 113 countries, fared better than Pakistan (75th position), Sri Lanka (77th Position), Nepal (79th position) and Bangladesh (84th position). But the country was way behind China (34th position).

In the food affordability category, Pakistan (with 52.6 points) scored better than India (50.2 points). Sri Lanka was also better at 62.9 points on the GFS Index 2021.

https://impact.economist.com/sustainability/project/food-security-index/index

Pakistan’s Prime Minister Imran Khan unveiled $709m package of subsidies for low-income households struggling with food price inflation.

https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2021/11/4/pakistan-pm-unveils-countrys-biggest-ever-welfare-programme

Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan unveiled a $709m package of food subsidies to ease the financial burden on low-income households as the prices of essentials continue to soar in the South Asian country.

Addressing the nation on Wednesday evening, Khan described the benefits package as “Pakistan’s biggest ever welfare programme”.

“This package is of Rs 120 billion ($709.2m), which the federal and provincial governments are giving jointly,” he said. “In this, we are [targeting] the three most important food items, ghee, flour and pulses.”

Under the plan, some 20 million qualifying low-income households will be entitled to a 30 percent discount on the purchase of the three items. The federal and provincial governments will make up the difference to retailers in the form of subsidy payments.

The subsidies will last for six months, Khan said, and are aimed at the poorest households, as classified by the government-run Ehsaas welfare programme.

Pakistani households have been dealing with spiralling consumer price inflation (CPI) in recent months, with October’s CPI clocking in at 9.2 percent compared with a year earlier.

Food inflation for core commodities has been particularly high, with the price of ghee increasing by 43 percent, flour by 12.97 percent and certain pulses by 17.62 percent over the last year, according to data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

The coronavirus pandemic hit the country’s economy hard, with economic growth slowing to 0.53 percent in 2020, according to the World Bank.

Prices for food, energy and other essential goods have skyrocketed around the world this year as countries cast off COVID-19 restrictions, triggering supply shortages and bottlenecks.

World food prices rose for a third straight month in October, the UN Food and Agricultural Organization said on Thursday, hitting a new 10 year high. Last month’s increase was driven by vegetable oils and cereals.

Khan blamed Pakistan’s inflation on international commodity prices, including petrol, claiming that his government had done a better job than others to absorb global price increases.

“What can we do about this? The inflation that is coming from outside. Let Allah make it so that we have all these things in our country, then we can reduce prices, but [not for things being imported],” he said.

Pakistan, which relies heavily on imports of essentials as well as other goods, has also been hit hard by a devaluation of its currency this year.

The Pakistani rupee has lost 13.1 percent of its value against the US dollar since May.

Khan’s government has expanded welfare spending during the pandemic to address unemployment and poverty, disbursing 179 billion rupees ($1.06bn) in grants to low-income families this year, according to government data.

Consumer Price Inflation, however, appears set to continue to increase, with Khan warning in his speech on Wednesday that the government would likely have to raise petroleum and diesel prices, in response to global oil price increases.

https://www.globalhungerindex.org/pakistan.html

In the 2022 Global Hunger Index, India ranks 107th out of the 121 countries with sufficient data to calculate 2022 GHI scores. With a score of 29.1, India has a level of hunger that is serious.

https://www.globalhungerindex.org/india.html

-------------------

India also ranks below Sri Lanka (64), Nepal (81), Bangladesh (84), and Pakistan (99). Afghanistan (109) is the only country in South Asia that performs worse than India on the index.

https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/india-ranks-107-out-of-121-countries-on-global-hunger-index/article66010797.ece

India ranks 107th among 121 countries on the Global Hunger Index, in which it fares worse than all countries in South Asia barring war-torn Afghanistan.

The Global Hunger Index (GHI) is a tool for comprehensively measuring and tracking hunger at global, regional, and national levels. GHI scores are based on the values of four component indicators — undernourishment, child stunting, child wasting and child mortality. Countries are divided into five categories of hunger on the basis of their score, which are ‘low’, ‘moderate’, ‘serious’, ‘alarming’ and ‘extremely alarming’.

Based on the values of the four indicators, a GHI score is calculated on a 100-point scale reflecting the severity of hunger, where zero is the best score (no hunger) and 100 is the worst.

India’s score of 29.1 places it in the ‘serious’ category. India also ranks below Sri Lanka (64), Nepal (81), Bangladesh (84), and Pakistan (99). Afghanistan (109) is the only country in South Asia that performs worse than India on the index.

Seventeen countries, including China, are collectively ranked between 1 and 17 for having a score of less than five.

India’s child wasting rate (low weight for height), at 19.3%, is worse than the levels recorded in 2014 (15.1%) and even 2000 (17.15), and is the highest for any country in the world and drives up the region’s average owing to India’s large population.

Prevalence of undernourishment, which is a measure of the proportion of the population facing chronic deficiency of dietary energy intake, has also risen in the country from 14.6% in 2018-2020 to 16.3% in 2019-2021. This translates into 224.3 million people in India considered undernourished.

But India has shown improvement in child stunting, which has declined from 38.7% to 35.5% between 2014 and 2022, as well as child mortality which has also dropped from 4.6% to 3.3% in the same comparative period. On the whole, India has shown a slight worsening with its GHI score increasing from 28.2 in 2014 to 29.1 in 2022. Though the GHI is an annual report, the rankings are not comparable across different years. The GHI score for 2022 can only be compared with scores for 2000, 2007 and 2014..

Globally, progress against hunger has largely stagnated in recent years. The 2022 GHI score for the world is considered “moderate”, but at 18.2 in 2022 is only a slight improvement from 19.1 in 2014. This is due to overlapping crises such as conflict, climate change, the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic as well as the Ukraine war, which has increased global food, fuel and fertiliser prices and is expected to "worsen hunger in 2023 and beyond."

The prevalence of undernourishment, one of the four indicators, shows that the share of people who lack regular access to sufficient calories is increasing and that 828 million people were undernourished globally in 2021.

There are 44 countries that currently have “serious” or “alarming” hunger levels and “without a major shift, neither the world as a whole nor approximately 46 countries are projected to achieve even low hunger as measured by the GHI by 2030,” notes the report.