World Pulses Day 2022: Pakistan's Daal Consumption in Sharp Decline

The United Nations has declared February 10 as World Pulses Day to recognize the importance of pulses or daal as global food. This recognition is driven as part of the effort to feed the global population in an environmentally sustainable way. Pulse crops have a lower carbon footprint than most foods because they require a small amount of fertilizer to grow, according to the United Nations. Pulses are protein and fiber rich food grown with a low carbon and water footprint as they are adapted to semi-arid conditions and can tolerate drought stress. Daal (pulses) global consumption is currently rising at a rate of about 9% annually.

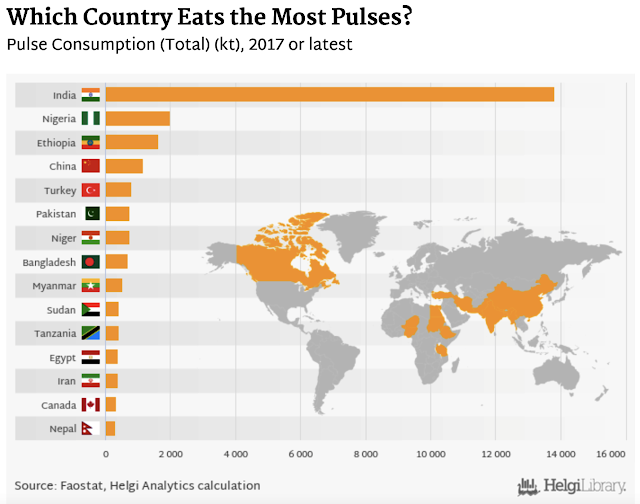

|

| Global Daal Consumption. Source: FAO, Helgi |

While the global daal consumption has significantly risen in recent years, Pakistan's per capita daal (pulse) consumption has sharply declined to about 7 kg/person from about 15 Kg/person in the 1960s, according to data released by Food and Agriculture Organization and reported in Pakistani media. Meat has replaced it as the main source of protein with per capita meat consumption rising from 11.7 kg in 2000 to 32 kg in 2016. It is projected to rise to 47 kg by 2020, according to a paper published in the Korean Journal of Food Science of Animal Resources.

Rising Incomes:

FAO report titled "State of Food and Agriculture in Asia and the Pacific Region" said rising incomes in developing nations are causing a shift from plant proteins — such as those found in pulses (daal) and beans — to more expensive animal proteins such as those found in meat and dairy.

|

| Food Consumption By Quintiles in Pakistan |

Pulses Consumption:

Per capita consumption of pulses in Pakistan has sharply declined from about 15 kg per person a year to about 7 kg per person a year, found a new report of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations. In spite of decline in consumption, Pakistan is still the second largest importer of pulses in the world. India is both the largest producer and the largest importer of pulses.

Chana (chickpeas), masoor, mung bean and mash are 4 important pulse crops in Pakistan. Last year, the combined production of all four crops was around 0.7 million tons with dominant share of 80 per cent of gram. The Pakistan Agricultural Research Council (PARC) says the total area under major pulse crops in Pakistan is about 1.3 million hectares.

Pakistan is now producing enough mung beans to meet its domestic needs. The first estimate of the crop for 2021-22 puts the legume output at 253,000 tons, more than enough to meet domestic demand for about 180,000 tons, according to Pakistani media reports.

Pakistan’s domestic production of chickpeas (chana) is estimated to be about 225,000 – 250,000 tons and it imports about 420,000 tons which adds to about 670,000 tons.

The first-ever production of kidney bean varieties at commercial level will begin soon as the Pakistan Agricultural Research Council (Parc) will release six new varieties of common bean varieties in the country, according to a Dawn newspaper report.

|

| Daal (Pulse) Consumption Trend in South Asia. Source: FAO |

In neighboring India, too, the consumption of pulse declined from about 22kg per person per year to about 15kg per person per year. In Sri Lanka, however, pulse consumption seemed to have fluctuated between 5kg and 10kg per person per year since 1960, except for a sharp drop from 1970 to 1985, the report said.

Dairy Consumption:

Economic Survey of Pakistan reported that Pakistanis consumed over 45 million tons of milk in fiscal year 2016-17, translating to about 220 Kg/person.

FAO's "State of Food and Agriculture in Asia and the Pacific Region" says that Mongolia and Pakistan are the only two among the 26 countries in Asia Pacific region where per capita milk consumption exceeded 370 grams/day.

Meat Consumption:

Pakistan's per capita meat consumption has nearly tripled from 11.7 kg in 2000 to 32 kg in 2016. It is projected to rise to 47 kg by 2020, according to a paper published by the United States National Library of Medicines at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The Organization for Economic Development (OECD) explains that meat demand increases with higher incomes and a shift - often due to growing urbanization - to food preferences that favor increased proteins from animal sources in diets.

|

| Meat Production in Pakistan. Source: FAO |

The NIH paper authors Mohammad Shoaib and Faraz Jamil point out that Pakistan's meat consumption of 32 Kg per person is only a third of the meat capita meat consumption in rich countries like Australia and the United States.

A study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and Nature magazine reports that Pakistanis are among the most carnivorous people in the world. After studying the eating habits of 176 countries, the authors found that average human being is at 2.21 trophic level. It put Pakistanis at 2.4, the same trophic level as Europeans and Americans. China and India are at 2.1 and 2.2 respectively.

Chicken Vs Daal:

In 2016, Pakistan's then finance minister Ishaq Dar suggested to his countrymen to eat chicken instead of daal (pulses or legumes). To some, the minister sounded like Queen Marie-Antoinette (wife of France's King Louis XVI) who reportedly said to hungry rioters during the French Revolution: “Qu'ils mangent de la brioche”—“Let them eat cake”?

It was indeed true that some varieties of daal were priced higher than chicken. For example, maash was selling at Rs. 260 per kilo, higher than chicken meat at Rs. 200 per kilo. But other daals such as mung, masur and chana were cheaper than chicken.

The reason for higher daal prices and relatively lower chicken prices can be found in the fact that Pakistan's livestock industry, particularly poultry farming, has seen significant growth that the nation's pulse crop harvests have not. Pakistan is among the world's largest importers of pulses.

Pakistan Among World's Largest Food Producers:

Pakistan's agriculture output is the 10th largest in the world. The country produces large and growing quantities of cereals, meat, milk, fruits and vegetables. Currently, Pakistan produces about 38 million tons of cereals (mainly wheat, rice and corn), 17 million tons of fruits and vegetables, 70 million tons of sugarcane, 60 million tons of milk and 4.5 million tons of meat. Total value of the nation's agricultural output exceeds $50 billion. Improving agriculture inputs and modernizing value chains can help the farm sector become much more productive to serve both domestic and export markets.

Summary:

Driven by sustainability concerns, the global daal consumption is rising at a rate of about 9% a year. However, per capita daal consumption in Pakistan is falling while meat and milk consumption is rising rising household incomes. Pulse consumption has sharply declined to about 7 kg/person from about 15 Kg/person in 2000, according to data released by the Food and Agriculture Organization and reported in Pakistani media. Meat has replaced it as the main source of protein with per capita meat consumption rising from 11.7 kg in 2000 to 32 kg in 2016. It is projected to rise to 47 kg by 2020, according to a paper published in the Korean Journal of Food Science of Animal Resources.

Haq's Musings

South Asia Investor Review

Chicken Cheaper Than Daal

Meat Industry in Pakistan

Pakistan Among World's Largest Food Producers

Meat and Dairy Revolution in Pakistan

Pakistanis Are Among the Most Carnivorous

Eid ul Azha: Multi-Billion Dollar Urban-to-Rural Transfer

Pakistan's Rural Economy

Pakistan Leads South Asia in Agriculture Value Addition

Comments

The Global Economy of Pulses edited by Vikas Rawal and Dorian Kalamvrezos Navarro, Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2019; pp xi + 174, price not indicated.

https://www.epw.in/journal/2021/17/book-reviews/production-trade-and-consumption-pulses.html

There appears to be a widely prevalent impression, particularly among the developed countries, that there are people and nations who do not know the “incredible properties” of pulses, and believe “that their nutritional value is generally not recognised and their consumption is frequently under-appreciated” (FAO 2016). Such a situation may be largely because pulses in farming and food are essentially a third world phenomenon. Almost 90% of the area under pulses and about 80% of output of pulses are in developing countries, and among them sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, where the world’s most of the poor and undernourished live, and for whom pulses are a critical source of protein, together account for about two-thirds of the area, and one-half of output of world’s pulses (Joshi and Rao 2016).

Pulse protein is a relatively large share of overall consumption in low-income countries, ranging from 10–35% in Africa. The country with the greatest pulse consumption is India. Protein from pulses represents 12.7% of total protein in the Indian diet. (Mc Dermott and Wyatt 2017)

To bring to light the crucial role that pulses play in health diets and sustainable agricultural production, the United Nations General Assembly declared 2016 as the International Year of Pulses (IYP) nominating the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) as the agency to implement it. Soon after the FAO came out with a report that was intended to popularise different aspects of pulses by illustrating (literally, as could be seen from the colourful pages all along in the report) the benefits ranging from nutrition to biodiversity—that included not only the expertise of the agriculture and nutrition sciences, but also appetising pulse recipes by some of the world-class chefs from across the regions (FAO 2016). But the volume under review, is of a different kind that seeks to explain “the world pulses situation and recent market trends, covering the themes of production, yields, utilisation, consumption, international trade and prices, as well as providing a medium-term outlook for pulses” (p x).

By Riaz Riazuddin former deputy governor of the State Bank of Pakistan.

https://www.dawn.com/news/1659441/consumption-habits-inflation

As households move to upper-income brackets, the share of spending on food consumption falls. This is known as Engel’s law. Empirical proof of this relationship is visible in the falling share of food from about 48pc in 2001-02 for the average household. This is an obvious indication that the real incomes of households have risen steadily since then, and inflation has not eaten up the entire rise in nominal incomes. Inflation seldom outpaces the rise in nominal incomes.

Coming back to eating habits, our main food spending is on milk. Of the total spending on food, about 25pc was spent on milk (fresh, packed and dry) in 2018-19, up from nearly 17pc in 2001-01. This is a good sign as milk is the most nourishing of all food items. This behaviour (largest spending on milk) holds worldwide. The direct consumption of milk by our households was about seven kilograms per month, or 84kg per year. Total milk consumption per capita is much higher because we also eat ice cream, halwa, jalebi, gulab jamun and whatnot bought from the market. The milk used in them is consumed indirectly. Our total per person per year consumption of milk was 168kg in 2018-19. This has risen from about 150kg in 2000-01. It was 107kg in 1949-50 showing considerable improvement since then.

Since milk is the single largest contributor in expenditure, its contribution to inflation should be very high. Thanks to milk price behaviour, it is seldom in the news as opposed to sugar and wheat, whose price trend, besides hurting the poor is also exploited for gaining political mileage. According to PBS, milk prices have risen from Rs82.50 per litre in October 2018 to Rs104.32 in October 2021. This is a three-year rise of 26.4pc, or per annum rise of 8.1pc. Another blessing related to milk is that the year-to-year variation in its prices is much lower than that of other food items. The three-year rise in CPI is about 30pc, or an average of 9.7pc per year till last month. Clearly, milk prices have contributed to containing inflation to a single digit during this period.

Next to milk is wheat and atta which constitute about 11.2pc of the monthly food expenditure — less than half of milk. Wheat and atta are our staple food and their direct consumption by the average household is 7kg per capita (84kg per capita per year). As we also eat naan from the tandoors, bread from bakeries etc, our indirect consumption of wheat and atta is 41kg per capita. Our total consumption of wheat and atta is about 125kg per capita per year. Our per person per day calorie intake has risen from about 2,078 in 1949-50 to 2,400 in 2001-02 and 2,580 in 2020-21. The per capita per day protein intake in grams increased from 63 to 67 to about 75 during these years. Does this indicate better health? To answer this, let us look at how we devour ghee and sugar. Also remember that each person requires a minimum of 2,100 calories and 60g of protein per day.

Undoubtedly, ghee, cooking oil and sugar have a special place in our culture. We are familiar with Urdu idioms mentioning ghee and shakkar. Two relate to our eating habits. We greet good news by saying ‘Aap kay munh may ghee shakkar’, which literally means that may your mouth be filled with ghee and sugar. We envy the fortune of others by saying ‘Panchon oonglian ghee mei’ (all five fingers immersed in ghee, or having the best of both worlds). These sayings reflect not only our eating trends, but also the inflation burden of the rising prices of these three items — ghee, cooking oil and sugar. Recall any wedding dinner. Ghee is floating in our plates.

Poultry is one of the fastest-growing industries in Pakistan with investments of about Rs1.1 trillion.

According to the Pakistan Poultry Association (PPA) report, the industry is the largest agro-based segment, generating employment and income for about 1.5 million people directly and indirectly.

The sector is growing at a fast pace of 10-12% per annum. At present, around Rs190 billion worth of agriculture products are being used by the poultry industry, speeding up the growth in the agriculture sector.

There are estimated 15,000 poultry farms throughout the country with their capacity ranging from 5,000 to 500,000 broilers. Pakistan’s poultry industry produces 1,245 million kilograms of chicken meat annually.

Ali Hasnain, a supervisor of the poultry sector, said that Pakistan’s poultry industry was no less than the international standards. “The poultry industry meets 50% of the total demand for meat in the country, and the rest is met by other meat products like beef, mutton and fish.”

“With the introduction of advanced technologies, more investments are coming around to cater to market needs and earn handsome revenues,” said Ali Hasnain, adding the poultry industry still had a lot of potential to contribute to the economy.

As per the PPA report, meat consumption per capita in Pakistan is less than the developed countries. The consumption of meat and eggs per capita is 6.2 kilograms and 56 eggs annually. In the developed world, the per capita meat consumption is 40 kilograms and 300 eggs annually.

According to the World Health Organisation, a person needs 27 grams of animal protein per day, while most people in Pakistan only consume 17 grams.

To meet the international standards of meat consumption, the supply and production need to be increased and prices need to be brought down so that consumers can get the required meat and egg consumption levels. An increase in production will certainly require more investments in the industry.

To boost production and bring down product rates, imports of poultry-related equipment should be exempted from duties and taxes.

In addition, as growers increasingly need land to establish sheds, the government should provide state land to investors at nominal rates to generate investments and more production.

Haniful Hassan, owner of a poultry farm, said that the current increase in prices of chicken was due to rise in prices of poultry feed. “The price of a feedbag has risen by 900 per bag in the last five months. We want the government to bring down the poultry feed rates to offset the price spiral,” he added.

Haniful Hassan called for establishing poultry research institutes, production directorates and a federal poultry board to provide research and training to farmers.

The government should also ensure easy availability of loans to people related to the industry.

Asafoetida sounds innocent enough -- it's a wild fennel plant native to Afghanistan, Iran and Uzbekistan.

The resin from its roots is used in Indian cooking -- usually after it's ground into powder and mixed with flour. To say it has a powerful smell would be an understatement. In fact, its scent is so pungent it might just be the most divisive ingredient in the country.

'Asa' means gum in Persian, and 'foetida' means stinky in Latin. But in India, it's just called hing.

If you accidentally get hing on your hands, it lingers no matter how many times you wash them. Put an unadulterated pinch on your tongue, and your mouth will start burning.

At the Khari Baoli market in old Delhi, for instance, hing even manages to 'out-smell' all the other spices.

"Hing is the mother of all base notes of Indian cooking," say Siddharth Talwar and Rhea Rosalind Ramji, co-founders of The School of Showbiz Chefs.

"It bridged the gap of flavors of onion and garlic that were prohibited due to religious beliefs in the largely vegetarian Indian communities such as Jain, Marwari and Gujarati. Despite the culinary diversity of India, hing is a constant."

Jains, for example, eschew onion, garlic and ginger in addition to not eating meat.

Ramji admits that the smell can be a challenge: Raw hing has been compared to rotten cabbage. It's even been given the nickname "devil's dung."

But a small amount goes a long way. Talwar advises that you put a miniscule amount of hing into hot oil.

Most people buy a powdered version that is mixed in with rice or wheat flour. However, more adventurous cooks will buy the solid crystal form, which looks like rock salt.

Some scholars credit Alexander the Great for first bringing hing to India.

"The popular theory is that Alexander's army encountered asafoetida in the Hindu Kush mountains and mistook it for the rare silphium plant, which has similar characteristics to asafoetida," explains culinary historian Dr. Ashish Chopra.

"They painstakingly carried the plant with them to India ... only to find out later that it wasn't what they (expected). Nevertheless, Indians have had their encounter with hing now; it came, it saw, and it stayed."

The professor adds that hing was used in some Greco-Roman cooking but didn't last long. These days, it's mostly absent from Western food, with one notable exception: Worcestershire sauce.

But as global food patterns and appetites change, some chefs are trying to remake their recipes by skipping onion and garlic in favor of asafetida.

According to Talwar, "hing can enhance the umami taste sensation essential for stews and stocks."

"The concept of umami was first introduced by Japanese food experts, but is now the fifth base note in gastronomy after sweet, bitter, sour and salty."

American company Burlap & Barrel even sells a Wild Hing blend made with turmeric, marketed toward people with garlic sensitivity or those following a low FODMAP diet.

https://www.nation.com.pk/02-Dec-2024/parc-introduced-10-high-yielding-pulses-seed-varieties-during-current-year

ISLAMABAD - The Pakistan Agriculture Research Council (PARC) Chairman Dr Ghulam Muhammad Ali has said that the Variety Evaluation Committee of the Council during current year has approved 10 high yielding pulses varieties to boost output of pulses in the country. Talking to media here on Sunday, he said that pulses play a crucial role in global food security and nutrition of the country, adding that Pakistan needs 1.56 million tons of pulses annually.

“We have become self-sufficient in mung production during 2021-22 which was 0.263 million tons against the total requirement of 0.180 million tons,” he said. These ten high-yielding pulse varieties are poised to revolutionise the pulse output, adding that now the country is focusing on increasing the production of other pulse crops, such as chickpea, lentil and mash bean. Out of the recommended 10 pulses varieties included 05 chickpeas and 01 mung bean variety of NIAB, Faisalabad, 01 lentil and 01 mung bean variety of Pulses Research Programme, NARC, Islamabad, he said, adding that 01 mung bean variety by Pulses Research Institute, AARI, Faisalabad and a mung bean variety of NIFA, Peshawar.

This achievement is due to the consistent backup support by PSDP, Pulses Project “Promoting Research for Productivity Enhancement in Pulses” to its research components throughout the country, he added. The chairman said that high-yielding, disease and climate-resilient varieties play an important role in improving pulse productivity. However, he was of the view that as the pulses gene pool has widened, therefore, all pulses scientists across the country are urged to focus on strengthening the pulses foundation seed production including BNS, Pre-basic and basic seed. Moreover, there was a need for a strong nexus among researchers and extension workers so that more seed can be produced to shrink the gap between pulses production and requirements in the country, he added.